Delay-Line Interpolation

As mentioned above, when an audio delay line needs to vary smoothly over time, some form of interpolation between samples is usually required to avoid ``zipper noise'' in the output signal as the delay length changes. There is a hefty literature on ``fractional delay'' in discrete-time systems, and the survey in [267] is highly recommended.

This section will describe the most commonly used cases. Linear interpolation is perhaps most commonly used because it is very straightforward and inexpensive, and because it sounds very good when the signal bandwidth is small compared with half the sampling rate. For a delay line in a nearly lossless feedback loop, such as in a vibrating string simulation, allpass interpolation is sometimes a better choice since it costs the same as linear interpolation in the first-order case and has no gain distortion. (Feedback loops can be very sensitive to gain distortions.) Finally, in later sections, some higher-order interpolation methods are described.

Linear Interpolation

Linear interpolation works by effectively drawing a straight line between two neighboring samples and returning the appropriate point along that line.

More specifically, let ![]() be a number between 0 and 1 which

represents how far we want to interpolate a signal

be a number between 0 and 1 which

represents how far we want to interpolate a signal ![]() between time

between time

![]() and time

and time ![]() . Then we can define the linearly interpolated

value

. Then we can define the linearly interpolated

value

![]() as follows:

as follows:

For

One-Multiply Linear Interpolation

Note that by factoring out ![]() , we can obtain a one-multiply

form,

, we can obtain a one-multiply

form,

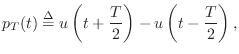

Fractional Delay Filtering by Linear Interpolation

A linearly interpolated delay line is depicted in Fig.4.1. In

contrast to Eq.![]() (4.1), we interpolate linearly between times

(4.1), we interpolate linearly between times

![]() and

and ![]() , and

, and ![]() is called the fractional delay in

samples. The first-order (linear-interpolating) filter following the

delay line in Fig.4.1 may be called a fractional delay

filter [267]. Equation (4.1), on the other hand, expresses the more

general case of an interpolated table lookup, where

is called the fractional delay in

samples. The first-order (linear-interpolating) filter following the

delay line in Fig.4.1 may be called a fractional delay

filter [267]. Equation (4.1), on the other hand, expresses the more

general case of an interpolated table lookup, where ![]() is

regarded as a table of samples and

is

regarded as a table of samples and

![]() is regarded as an

interpolated table-lookup based on the samples stored at indices

is regarded as an

interpolated table-lookup based on the samples stored at indices ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

The difference between a fractional delay filter and an interpolated table lookup is that table-lookups can ``jump around,'' while fractional delay filters receive a sequential stream of input samples and produce a corresponding sequential stream of interpolated output values. As a result of this sequential access, fractional delay filters may be recursive IIR digital filters (provided the desired delay does not change too rapidly over time). In contrast, ``random-access'' interpolated table lookups are typically implemented using weighted linear combinations, making them equivalent to nonrecursive FIR filters in the sequential case.5.1

The C++ class implementing a linearly interpolated delay line in the Synthesis Tool Kit (STK) is called DelayL.

The frequency response of linear interpolation for fixed fractional

delay (![]() fixed in Fig.4.1) is shown in Fig.4.2.

From inspection of Fig.4.1, we see that linear interpolation is

a one-zero FIR filter. When used to provide a fixed fractional delay,

the filter is linear and time-invariant (LTI). When the fractional delay

fixed in Fig.4.1) is shown in Fig.4.2.

From inspection of Fig.4.1, we see that linear interpolation is

a one-zero FIR filter. When used to provide a fixed fractional delay,

the filter is linear and time-invariant (LTI). When the fractional delay ![]() changes over time, it is a linear time-varying filter.

changes over time, it is a linear time-varying filter.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/linear1}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img937.png) |

Linear interpolation sounds best when the signal is oversampled. Since natural audio spectra tend to be relatively concentrated at low frequencies, linear interpolation tends to sound very good at high sampling rates.

When interpolation occurs inside a feedback loop, such as in digital waveguide models for vibrating strings (see Chapter 6), errors in the amplitude response can be highly audible (particularly when the loop gain is close to 1, as it is for steel strings, for example). In these cases, it is possible to eliminate amplitude error (at some cost in delay error) by using an allpass filter for delay-line interpolation.

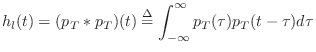

First-Order Allpass Interpolation

A delay line interpolated by a first-order allpass filter is drawn in Fig.4.3.

Intuitively, ramping the coefficients of the allpass gradually ``grows'' or ``hides'' one sample of delay. This tells us how to handle resets when crossing sample boundaries.

The difference equation is

![\begin{eqnarray*}

{\hat x}(n-\Delta) \isdef y(n) &=& \eta \cdot x(n) + x(n-1) - ...

...y(n-1) \\

&=& \eta \cdot \left[ x(n) - y(n-1)\right] + x(n-1).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img939.png)

Thus, like linear interpolation, first-order allpass interpolation requires only one multiply and two adds per sample of output.

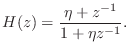

The transfer function is

At low frequencies (

Figure 4.4 shows the phase delay of the first-order digital allpass filter for a variety of desired delays at dc. Since the amplitude response of any allpass is 1 at all frequencies, there is no need to plot it.

The first-order allpass interpolator is generally controlled by

setting its dc delay to the desired delay. Thus, for a given desired

delay ![]() , the allpass coefficient is (from

Eq.

, the allpass coefficient is (from

Eq.![]() (4.3))

(4.3))

Note that, unlike linear interpolation, allpass interpolation is not suitable for ``random access'' interpolation in which interpolated values may be requested at any arbitrary time in isolation. This is because the allpass is recursive so that it must run for enough samples to reach steady state. However, when the impulse response is reasonably short, as it is for delays near one sample, it can in fact be used in ``random access mode'' by giving it enough samples with which to work.

The STK class implementing allpass-interpolated delay is DelayA.

Minimizing First-Order Allpass Transient Response

In addition to approaching a pole-zero cancellation at ![]() , another

undesirable artifact appears as

, another

undesirable artifact appears as

![]() : The transient

response also becomes long when the pole at

: The transient

response also becomes long when the pole at ![]() gets close to

the unit circle.

gets close to

the unit circle.

A plot of the impulse response for

![]() is shown in

Fig.4.6. We see a lot of ``ringing'' near half the sampling rate.

We actually should expect this from the nonlinear-phase

distortion which is clearly evident near half the sampling rate in

Fig.4.4. We can interpret this phenomenon as the signal

components near half the sampling rate being delayed by different

amounts than other frequencies, therefore ``sliding out of alignment''

with them.

is shown in

Fig.4.6. We see a lot of ``ringing'' near half the sampling rate.

We actually should expect this from the nonlinear-phase

distortion which is clearly evident near half the sampling rate in

Fig.4.4. We can interpret this phenomenon as the signal

components near half the sampling rate being delayed by different

amounts than other frequencies, therefore ``sliding out of alignment''

with them.

For audio applications, we would like to keep the impulse-response

duration short enough to sound ``instantaneous.'' That is, we do not

wish to have audible ``ringing'' in the time domain near ![]() . For

high quality sampling rates, such as larger than

. For

high quality sampling rates, such as larger than ![]() kHz, there

is no issue of direct audibility, since the ringing is above the range

of human hearing. However, it is often convenient, especially for

research prototyping, to work at lower sampling rates where

kHz, there

is no issue of direct audibility, since the ringing is above the range

of human hearing. However, it is often convenient, especially for

research prototyping, to work at lower sampling rates where ![]() is

audible. Also, many commercial products use such sampling rates to

save costs.

is

audible. Also, many commercial products use such sampling rates to

save costs.

Since the time constant of decay, in samples, of the impulse response

of a pole of radius ![]() is approximately

is approximately

For example, suppose 100 ms is chosen as the maximum ![]() allowed

at a sampling rate of

allowed

at a sampling rate of

![]() . Then applying the above constraints

yields

. Then applying the above constraints

yields

![]() , corresponding to the allowed delay range

, corresponding to the allowed delay range

![]() .

.

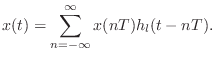

Linear Interpolation as Resampling

Convolution Interpretation

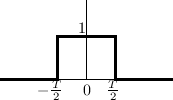

Linearly interpolated fractional delay is equivalent to filtering and resampling a weighted impulse train (the input signal samples) with a continuous-time filter having the simple triangular impulse response

Convolution of the weighted impulse train with

This continuous result can then be resampled at the desired fractional delay.

In discrete time processing, the operation Eq.![]() (4.5) can be

approximated arbitrarily closely by digital upsampling by a

large integer factor

(4.5) can be

approximated arbitrarily closely by digital upsampling by a

large integer factor ![]() , delaying by

, delaying by ![]() samples (an integer), then

finally downsampling by

samples (an integer), then

finally downsampling by ![]() , as depicted in Fig.4.7

[96]. The integers

, as depicted in Fig.4.7

[96]. The integers ![]() and

and ![]() are chosen so that

are chosen so that

![]() , where

, where ![]() the desired fractional delay.

the desired fractional delay.

The convolution interpretation of linear interpolation, Lagrange interpolation, and others, is discussed in [407].

Frequency Response of Linear Interpolation

Since linear interpolation can be expressed as a convolution of the

samples with a triangular pulse, we can derive the frequency

response of linear interpolation. Figure 4.7 indicates that

the triangular pulse ![]() serves as an anti-aliasing lowpass

filter for the subsequent downsampling by

serves as an anti-aliasing lowpass

filter for the subsequent downsampling by ![]() . Therefore, it should

ideally ``cut off'' all frequencies higher than

. Therefore, it should

ideally ``cut off'' all frequencies higher than ![]() .

.

Triangular Pulse as Convolution of Two Rectangular Pulses

The 2-sample wide triangular pulse ![]() (Eq.

(Eq.![]() (4.4)) can be

expressed as a convolution of the one-sample rectangular pulse with

itself.

(4.4)) can be

expressed as a convolution of the one-sample rectangular pulse with

itself.

The one-sample rectangular pulse is shown in Fig.4.8 and may be defined analytically as

![$\displaystyle u(t) \isdef \left\{\begin{array}{ll}

1, & t\geq 0 \\ [5pt]

0, & t<0 \\

\end{array}\right..

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img968.png)

Linear Interpolation Frequency Response

Since linear interpolation is a convolution of the samples with a

triangular pulse

![]() (from Eq.

(from Eq.![]() (4.5)),

the frequency response of the interpolation is given by the Fourier

transform

(4.5)),

the frequency response of the interpolation is given by the Fourier

transform ![]() , which yields a

sinc

, which yields a

sinc![]() function. This frequency

response applies to linear interpolation from discrete time to

continuous time. If the output of the interpolator is also sampled,

this can be modeled by sampling the continuous-time interpolation

result in Eq.

function. This frequency

response applies to linear interpolation from discrete time to

continuous time. If the output of the interpolator is also sampled,

this can be modeled by sampling the continuous-time interpolation

result in Eq.![]() (4.5), thereby aliasing the

sinc

(4.5), thereby aliasing the

sinc![]() frequency

response, as shown in Fig.4.9.

frequency

response, as shown in Fig.4.9.

In slightly more detail, from

![]() , and

, and

![]() sinc

sinc![]() , we have

, we have

The Fourier transform of ![]() is the same function aliased on

a block of size

is the same function aliased on

a block of size ![]() Hz. Both

Hz. Both ![]() and its alias are plotted

in Fig.4.9. The example in this figure pertains to an

output sampling rate which is

and its alias are plotted

in Fig.4.9. The example in this figure pertains to an

output sampling rate which is ![]() times that of the input signal.

In other words, the input signal is upsampled by a factor of

times that of the input signal.

In other words, the input signal is upsampled by a factor of ![]() using linear interpolation. The ``main lobe'' of the interpolation

frequency response

using linear interpolation. The ``main lobe'' of the interpolation

frequency response ![]() contains the original signal bandwidth;

note how it is attenuated near half the original sampling rate (

contains the original signal bandwidth;

note how it is attenuated near half the original sampling rate (![]() in Fig.4.9). The ``sidelobes'' of the frequency response

contain attenuated copies of the original signal bandwidth (see

the DFT stretch theorem), and thus constitute spectral imaging

distortion in the final output (sometimes also referred to as a kind

of ``aliasing,'' but, for clarity, that term will not be used for

imaging distortion in this book). We see that the frequency response

of linear interpolation is less than ideal in two ways:

in Fig.4.9). The ``sidelobes'' of the frequency response

contain attenuated copies of the original signal bandwidth (see

the DFT stretch theorem), and thus constitute spectral imaging

distortion in the final output (sometimes also referred to as a kind

of ``aliasing,'' but, for clarity, that term will not be used for

imaging distortion in this book). We see that the frequency response

of linear interpolation is less than ideal in two ways:

- The spectrum is ``rolled'' off near half the sampling rate. In fact, it is nowhere flat within the ``passband'' (-1 to 1 in Fig.4.9).

- Spectral imaging distortion is suppressed by only 26 dB (the level of the first sidelobe in Fig.4.9.

Special Cases

In the limiting case of ![]() , the input and output sampling rates are

equal, and all sidelobes of the frequency response

, the input and output sampling rates are

equal, and all sidelobes of the frequency response ![]() (partially

shown in Fig.4.9) alias into the main lobe.

(partially

shown in Fig.4.9) alias into the main lobe.

If the output is sampled at the same exact time instants as the input

signal, the input and output are identical. In terms of the aliasing

picture of the previous section, the frequency response aliases to a

perfect flat response over

![]() , with all spectral images

combining coherently under the flat gain. It is important in this

reconstruction that, while the frequency response of the underlying

continuous interpolating filter is aliased by sampling, the signal

spectrum is only imaged--not aliased; this is true for all positive

integers

, with all spectral images

combining coherently under the flat gain. It is important in this

reconstruction that, while the frequency response of the underlying

continuous interpolating filter is aliased by sampling, the signal

spectrum is only imaged--not aliased; this is true for all positive

integers ![]() and

and ![]() in Fig.4.7.

in Fig.4.7.

More typically, when linear interpolation is used to provide

fractional delay, identity is not obtained. Referring again to

Fig.4.7, with ![]() considered to be so large that it is

effectively infinite, fractional-delay by

considered to be so large that it is

effectively infinite, fractional-delay by ![]() can be modeled as

convolving the samples

can be modeled as

convolving the samples ![]() with

with

![]() followed by sampling

at

followed by sampling

at ![]() . In this case, a linear phase term has been introduced in

the interpolator frequency response, giving,

. In this case, a linear phase term has been introduced in

the interpolator frequency response, giving,

Large Delay Changes

When implementing large delay length changes (by many samples), a useful implementation is to cross-fade from the initial delay line configuration to the new configuration:

- Computational requirements are doubled during the cross-fade.

- The cross-fade should occur over a time interval long enough to yield a smooth result.

- The new delay interpolation filter, if any, may be initialized in advance

of the cross-fade, for maximum smoothness. Thus, if the transient

response of the interpolation filter is

samples, the new delay-line

+ interpolation filter can be ``warmed up'' (executed) for

samples, the new delay-line

+ interpolation filter can be ``warmed up'' (executed) for  time steps before beginning the cross-fade. If the cross-fade time

is long compared with the interpolation filter duration, ``pre-warming''

is not necessary.

time steps before beginning the cross-fade. If the cross-fade time

is long compared with the interpolation filter duration, ``pre-warming''

is not necessary.

- This is not a true ``morph'' from one delay length to another since we do not pass through the intermediate delay lengths. However, it avoids a potentially undesirable Doppler effect.

- A single delay line can be shared such that the cross-fade occurs from one read-pointer (plus associated filtering) to another.

Next Section:

Lagrange Interpolation

Previous Section:

FDN Reverberation

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/delayli}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img934.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/delayai}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img938.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/allpass1}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img943.png)

![\includegraphics[width=4.8in]{eps/ap1pz}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img949.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/ap1ir}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img952.png)

![$\displaystyle h_l(t) = \left\{\begin{array}{ll} 1-\left\vert t/T\right\vert, & ...

...ght\vert\leq T, \\ [5pt] 0, & \hbox{otherwise}. \\ \end{array} \right. \protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img959.png)

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\twidth]{eps/polyphaseli}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img963.png)

![\includegraphics[width=3in]{eps/sincsquared}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img979.png)