Wave Digital Modeling Examples

This section presents a series of examples, working up from very simple to more complicated situations.

``Piano hammer in flight''

Suppose we wish to model a situation in which a mass of size ![]() kilograms is traveling with a constant velocity. This is an

appropriate model for a piano hammer after its key has been pressed

and before the hammer has reached the string.

kilograms is traveling with a constant velocity. This is an

appropriate model for a piano hammer after its key has been pressed

and before the hammer has reached the string.

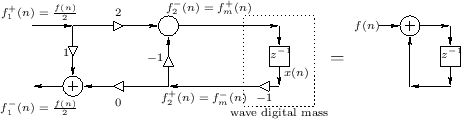

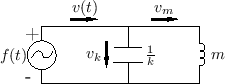

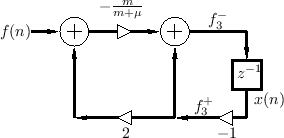

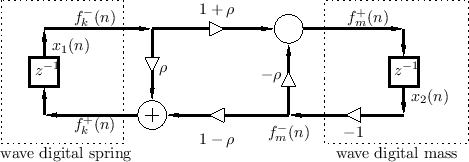

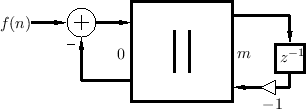

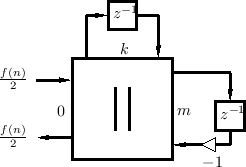

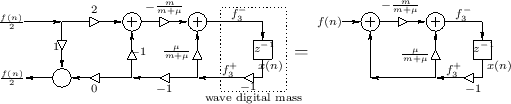

Figure F.2 shows the ``wave digital mass'' derived previously.

The derivation consisted of inserting an infinitesimal

waveguideF.3 having (real) impedance

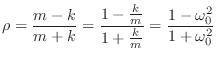

![]() , solving for the force-wave reflectance of the mass as seen from

the waveguide, and then mapping it to the discrete time domain using

the bilinear transform.

, solving for the force-wave reflectance of the mass as seen from

the waveguide, and then mapping it to the discrete time domain using

the bilinear transform.

We now need to attach the other end of the transmission line to a ``force source'' which applies a force of zero newtons to the mass. In other words, we need to terminate the line in a way that corresponds to zero force.

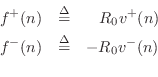

Let the force-wave components entering and leaving the mass

be denoted ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively (i.e., we are dropping

the subscript `d' in Fig.F.2).

The physical force associated with the mass is

, respectively (i.e., we are dropping

the subscript `d' in Fig.F.2).

The physical force associated with the mass is

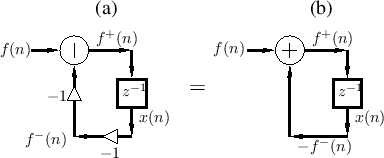

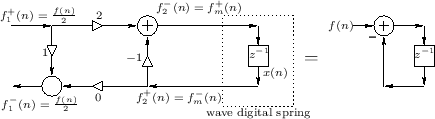

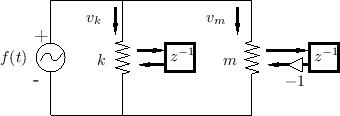

Figure F.8a (left portion) illustrates what we derived

by physical reasoning, and as such, it is most appropriate as a

physical model of the constant-velocity mass. However, for actual

implementation, Fig.F.8b would be more typical in

practice. This is because we can always negate the state variable

![]() if needed to convert it from

if needed to convert it from

![]() to

to

![]() . It is

very common to see final simplifications like this to maximize

efficiency.

. It is

very common to see final simplifications like this to maximize

efficiency.

Note that Fig.F.8b can be interpreted physically as a wave

digital spring displaced by a constant force

![]() .

.

Extracting Physical Quantities

Since we are using a force-wave simulation, the state variable ![]() (delay element output) is in units of physical force (newtons).

Specifically,

(delay element output) is in units of physical force (newtons).

Specifically,

![]() . (The physical force is, of

course, 0, while its traveling-wave components are not 0 unless the

mass is at rest.) Using the fundamental relations relating traveling

force and velocity waves

. (The physical force is, of

course, 0, while its traveling-wave components are not 0 unless the

mass is at rest.) Using the fundamental relations relating traveling

force and velocity waves

where ![]() here, it is easy to convert the state variable

here, it is easy to convert the state variable ![]() to

other physical units, as we now demonstrate.

to

other physical units, as we now demonstrate.

The velocity of the mass, for example, is given by

The kinetic energy of the mass is given by

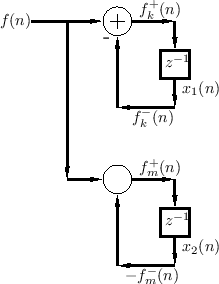

Force Driving a Mass

Suppose now that we wish to drive the mass along a frictionless

surface using a variable force ![]() . This is similar to the

previous example, except that we now want the traveling-wave

components of the force on the mass to sum to

. This is similar to the

previous example, except that we now want the traveling-wave

components of the force on the mass to sum to ![]() instead of 0:

instead of 0:

The simplified form in Fig.F.9b can be interpreted as a wave

digital spring with applied force ![]() delivered from an infinite

source impedance. That is, when the applied force goes to zero, the

termination remains rigid at the current displacement.

delivered from an infinite

source impedance. That is, when the applied force goes to zero, the

termination remains rigid at the current displacement.

A More Formal Derivation of the Wave Digital Force-Driven Mass

Above we derived how to handle the external force by direct physical reasoning. In this section, we'll derive it using a more general step-by-step procedure which can be applied systematically to more complicated situations.

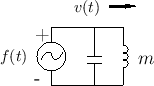

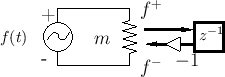

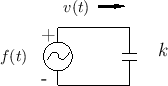

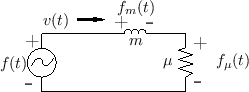

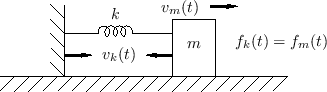

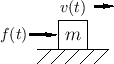

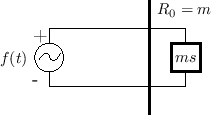

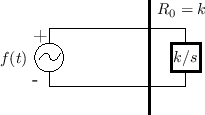

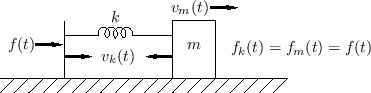

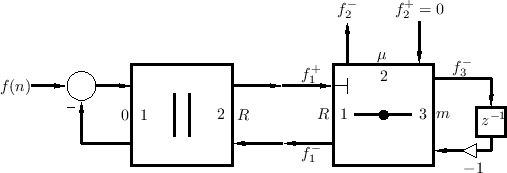

Figure F.10 gives the physical picture of a free mass driven by

an external force in one dimension. Figure F.11 shows the

electrical equivalent circuit for this scenario in which the external

force is represented by a voltage source emitting ![]() volts,

and the mass is modeled by an inductor having the value

volts,

and the mass is modeled by an inductor having the value ![]() Henrys.

Henrys.

|

The next step is to convert the voltages and currents in the

electrical equivalent circuit to wave variables.

Figure F.12 gives an intermediate equivalent circuit in which

an infinitesimal transmission line section with real impedance ![]() has been inserted to facilitate the computation of the wave-variable

reflectance, as we did in §F.1.1 to derive Eq.

has been inserted to facilitate the computation of the wave-variable

reflectance, as we did in §F.1.1 to derive Eq.![]() (F.1).

(F.1).

|

Figure F.13 depicts a next intermediate equivalent circuit in

which the mass has been replaced by its reflectance (using ``![]() ''

to denote the continuous-time reflectance

''

to denote the continuous-time reflectance

![]() , as derived in

§F.1.1). The infinitesimal transmission-line section is now represented

by a ``resistor'' since, when the voltage source is initially

``switched on'', it only ``sees'' a real resistance having the value

, as derived in

§F.1.1). The infinitesimal transmission-line section is now represented

by a ``resistor'' since, when the voltage source is initially

``switched on'', it only ``sees'' a real resistance having the value

![]() Ohms (the waveguide interface). After a short period of time

determined by the reflectance of the mass,F.4 ``return waves'' from the mass result in an ultimately

reactive impedance. This of course must be the case because the

mass does not dissipate energy. Therefore, the ``resistor'' of

Ohms (the waveguide interface). After a short period of time

determined by the reflectance of the mass,F.4 ``return waves'' from the mass result in an ultimately

reactive impedance. This of course must be the case because the

mass does not dissipate energy. Therefore, the ``resistor'' of ![]() Ohms is not a resistor in the usual sense since it does not convert

potential energy (the voltage drop across it) into heat. Instead, it

converts potential energy into propagating waves with 100%

efficiency. Since all of this wave energy is ultimately reflected by

the terminating element (mass, spring, or any combination of masses

and springs), the net effect is a purely reactive impedance, as we

know it must be.

Ohms is not a resistor in the usual sense since it does not convert

potential energy (the voltage drop across it) into heat. Instead, it

converts potential energy into propagating waves with 100%

efficiency. Since all of this wave energy is ultimately reflected by

the terminating element (mass, spring, or any combination of masses

and springs), the net effect is a purely reactive impedance, as we

know it must be.

|

To complete the wave digital model, we need to connect our wave

digital mass to an ideal force source which asserts the value ![]() each sample time. Since an ideal force source has a zero internal

impedance, we desire a parallel two-port junction which connects the

impedances

each sample time. Since an ideal force source has a zero internal

impedance, we desire a parallel two-port junction which connects the

impedances ![]() (

(

![]() ) and

) and ![]() (

(

![]() ), as

shown in Fig.F.14. From

Eq.

), as

shown in Fig.F.14. From

Eq.![]() (F.18) we have that the common junction force is equal to

(F.18) we have that the common junction force is equal to

from which we conclude that

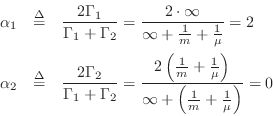

Since

![]() and

and

![]() for this model, the reflection

coefficient seen on port 1 is

for this model, the reflection

coefficient seen on port 1 is

![]() . The

transmission coefficient from port 1 is

. The

transmission coefficient from port 1 is ![]() . In the opposite

direction, the reflection coefficient on port 2 is

. In the opposite

direction, the reflection coefficient on port 2 is ![]() , and

the transmission coefficient from port 2 is

, and

the transmission coefficient from port 2 is

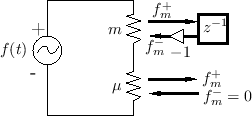

![]() . The final

result, drawn in Kelly-Lochbaum form (see §F.2.1), is

diagrammed in Fig.F.15, as well as the result of some

elementary simplifications. The final model is the same as in

Fig.F.9, as it should be.

. The final

result, drawn in Kelly-Lochbaum form (see §F.2.1), is

diagrammed in Fig.F.15, as well as the result of some

elementary simplifications. The final model is the same as in

Fig.F.9, as it should be.

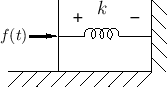

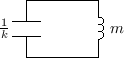

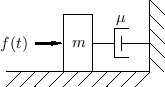

Force Driving a Spring against a Wall

For this example, we have an external force ![]() driving a spring

driving a spring

![]() which is terminated on the other end at a rigid wall.

Figure F.16 shows the physical diagram

and the electrical equivalent circuit is given in

Fig.F.17.

which is terminated on the other end at a rigid wall.

Figure F.16 shows the physical diagram

and the electrical equivalent circuit is given in

Fig.F.17.

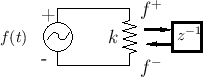

Figure F.18 depicts the insertion of an infinitesimal transmission line, and Fig.F.19 shows the result of converting the spring impedance to wave variable form.

|

The two-port adaptor needed for this problem is the same as that for the force-driven mass, and the final result is shown in Fig.F.20.

Note that the spring model is being driven by a force from a zero source impedance, in contrast with the infinite source impedance interpretation of Fig.F.8b as a compressed spring. In this case, if the driving force goes to zero, the spring force goes immediately to zero (``free termination'') rather than remaining fixed.

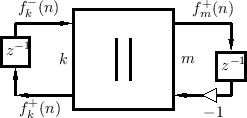

Spring and Free Mass

For this example, we have an external force ![]() driving a spring

driving a spring

![]() which in turn drives a free mass

which in turn drives a free mass ![]() . Since the force on the

spring and the mass are always the same, they are formally

``parallel'' impedances.

. Since the force on the

spring and the mass are always the same, they are formally

``parallel'' impedances.

This problem is easier than it may first appear since an ideal ``force source'' (i.e., one with a zero source impedance) driving impedances in parallel can be analyzed separately for each parallel branch. That is, the system is equivalent to one in which the mass and spring are not connected at all, and each has its own copy of the force source. With this insight in mind, one can immediately write down the final wave-digital model shown in Fig.F.25. However, we will go ahead and analyze this case more formally since it has some interesting features.

Figure F.21 shows the physical diagram of the spring-mass system driven by an external force. The electrical equivalent circuit appears in Fig.F.22, and the first stage of a wave-variable conversion is shown in Fig.F.23.

|

|

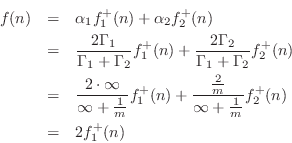

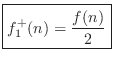

For this example we need a three-port parallel adaptor, as shown in

Fig.F.24 (along with its attached mass and spring).

The port impedances are 0, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , yielding alpha parameters

, yielding alpha parameters

![]() and

and

![]() . The final result, after the

same sorts of elementary simplifications as in the previous example,

is shown in Fig.F.25. As predicted, a force source driving

elements in parallel is equivalent to a set of independent

force-driven elements.

. The final result, after the

same sorts of elementary simplifications as in the previous example,

is shown in Fig.F.25. As predicted, a force source driving

elements in parallel is equivalent to a set of independent

force-driven elements.

|

From this and the preceding example, we can see a general pattern:

Whenever there is an ideal force source driving a parallel

junction, then

![]() and all other port admittances are

finite. In this case, we always obtain

and all other port admittances are

finite. In this case, we always obtain

![]() and

and

![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

Mass and Dashpot in Series

This is our first example illustrating a series connection of wave digital elements. Figure F.26 gives the physical scenario of a simple mass-dashpot system, and Fig.F.27 shows the equivalent circuit. Replacing element voltages and currents in the equivalent circuit by wave variables in an infinitesimal waveguides produces Fig.F.28.

|

|

The system can be described as an ideal force source ![]() connected

in parallel with the series connection of mass

connected

in parallel with the series connection of mass ![]() and

dashpot

and

dashpot ![]() .

Figure F.29 illustrates the resulting wave digital filter.

Note that the ports are now numbered for reference. Two more symbols

are introduced in this figure: (1) the horizontal line with a dot in

the middle indicating a series adaptor, and (2) the indication of a

reflection-free port on input 1 of the series adaptor (signal

.

Figure F.29 illustrates the resulting wave digital filter.

Note that the ports are now numbered for reference. Two more symbols

are introduced in this figure: (1) the horizontal line with a dot in

the middle indicating a series adaptor, and (2) the indication of a

reflection-free port on input 1 of the series adaptor (signal

![]() ). Recall that a reflection-free port is always necessary

when connecting two adaptors together, to avoid creating a delay-free

loop.

). Recall that a reflection-free port is always necessary

when connecting two adaptors together, to avoid creating a delay-free

loop.

Let's first calculate the impedance ![]() necessary to make input 1 of

the series adaptor reflection free. From Eq.

necessary to make input 1 of

the series adaptor reflection free. From Eq.![]() (F.37), we require

(F.37), we require

The parallel adaptor, viewed alone, is equivalent to a force source

driving impedance ![]() . It is therefore realizable as in

Fig.F.20 with the wave digital spring replaced by the

mass-dashpot assembly in

Fig.F.29. However, we can also carry out a quick analysis

to verify this: The alpha parameters are

. It is therefore realizable as in

Fig.F.20 with the wave digital spring replaced by the

mass-dashpot assembly in

Fig.F.29. However, we can also carry out a quick analysis

to verify this: The alpha parameters are

Therefore, the reflection coefficient seen at port 1 of the parallel

adaptor is

![]() , and the Kelly-Lochbaum scattering

junction depicted in Fig.F.20 is verified.

, and the Kelly-Lochbaum scattering

junction depicted in Fig.F.20 is verified.

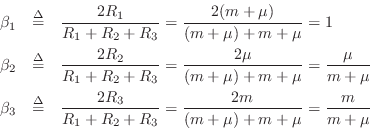

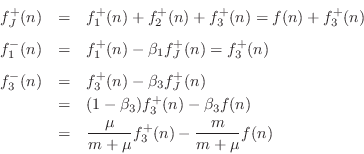

Let's now calculate the internals of the series adaptor in

Fig.F.29. From Eq.![]() (F.26), the beta parameters are

(F.26), the beta parameters are

Following Eq.![]() (F.30), the series adaptor computes

(F.30), the series adaptor computes

We do not need to explicitly compute

![]() because it goes into a

purely resistive impedance

because it goes into a

purely resistive impedance ![]() and produces no return wave. For the

same reason,

and produces no return wave. For the

same reason,

![]() .

Figure F.30 shows a wave flow diagram of the computations derived,

together with the result of elementary simplifications.

.

Figure F.30 shows a wave flow diagram of the computations derived,

together with the result of elementary simplifications.

|

Because the difference of the two coefficients in Fig.F.30 is 1, we can easily derive the one-multiply form in Fig.F.31.

Checking the WDF against the Analog Equivalent Circuit

Let's check our result by comparing the transfer function from the input force to the force on the mass in both the discrete- and continuous-time cases.

For the discrete-time case, we have

We now need

![]() .

To simplify notation, define the two coefficients as

.

To simplify notation, define the two coefficients as

From Figure F.30, we can write

![\begin{eqnarray*}

F^{-}_3(z) &=& -a\left[F(z)-z^{-1}F^{-}_3(z)\right] + b\left[-...

...\,\,\quad

F^{-}_3(z) &=& -a\frac{F(z)}{1-(a-b)z^{-1}F^{-}_3(z)}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img4987.png)

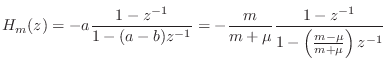

Thus, the desired transfer function is

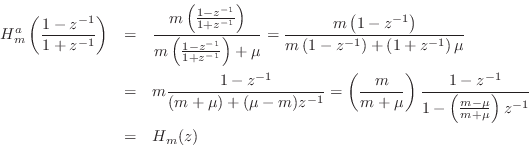

We now wish to compare this result to the bilinear transform of the corresponding analog transfer function. From Figure F.27, we can recognize the mass and dashpot as voltage divider:

Thus, we have verified that the force transfer-function from the driving force to the mass is identical in the discrete- and continuous-time models, except for the bilinear transform frequency warping in the discrete-time case.

Wave Digital Mass-Spring Oscillator

Let's look again at the mass-spring oscillator of §F.3.4, but this time without the driving force (which effectively decouples the mass and spring into separate first-order systems). The physical diagram and equivalent circuit are shown in Fig.F.32 and Fig.F.33, respectively.

Note that the mass and spring can be regarded as being in parallel or

in series. Under the parallel interpretation, we have the WDF shown

in Fig.F.34 and Fig.F.35.F.5

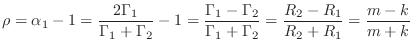

The reflection coefficient ![]() can be computed, as usual, from

the first alpha parameter:

can be computed, as usual, from

the first alpha parameter:

Oscillation Frequency

From Fig.F.33, we can see that the impedance of the parallel combination of the mass and spring is given by

(using the product-over-sum rule for combining impedances in parallel). The poles of this impedance are given by the roots of the denominator polynomial in

The resonance frequency of the mass-spring oscillator is therefore

Since the poles

We can now write reflection coefficient ![]() (see Fig.F.35) as

(see Fig.F.35) as

DC Analysis of the WD Mass-Spring Oscillator

Considering the dc case first (![]() ), we see from Fig.F.35

that the state variable

), we see from Fig.F.35

that the state variable ![]() will circulate unchanged in the

isolated loop on the left. Let's call this value

will circulate unchanged in the

isolated loop on the left. Let's call this value

![]() . Then the physical force on the spring is always equal to

. Then the physical force on the spring is always equal to

The loop on the right in Fig.F.35 receives

At first, this result might appear to contradict conservation of energy, since the state amplitude seems to be growing without bound. However, the physical force is fortunately better behaved:

Since the spring and mass are connected in parallel, it must be the true that they are subjected to the same physical force at all times. Comparing Equations (F.41-F.43) verifies this to be the case.

WD Mass-Spring Oscillator at Half the Sampling Rate

Under the bilinear transform, the ![]() maps to

maps to ![]() (half the

sampling rate). It is therefore no surprise that given

(half the

sampling rate). It is therefore no surprise that given

![]() (

(![]() ), inspection of Fig.F.35 reveals

that any alternating sequence (sinusoid sampled at half the sampling

rate) will circulate unchanged in the loop on the right, which is now

isolated. Let

), inspection of Fig.F.35 reveals

that any alternating sequence (sinusoid sampled at half the sampling

rate) will circulate unchanged in the loop on the right, which is now

isolated. Let

![]() denote this alternating sequence.

The loop on the left receives

denote this alternating sequence.

The loop on the left receives

![]() and adds

and adds

![]() to

it, i.e.,

to

it, i.e.,

![]() .

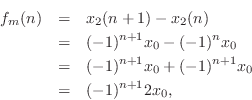

If we start out with

.

If we start out with ![]() and

and

![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]() , or

, or

which agrees with the spring, as it must.

Linearly Growing State Variables in WD Mass-Spring Oscillator

It may seem disturbing that such a simple, passive, physically

rigorous simulation of a mass-spring oscillator should have to make

use of state variables which grow without bound for the limiting cases

of simple harmonic motion at frequencies zero and half the sampling

rate. This is obviously a valid concern in practice as well.

However, it is easy to show that this only happens at dc and ![]() ,

and that there is a true degeneracy at these frequencies, even in the

physics. For all frequencies in the audio range (e.g., for typical

sampling rates), such state variable growth cannot occur. Let's take

closer look at this phenomenon, first from a signal processing point

of view, and second from a physical point of view.

,

and that there is a true degeneracy at these frequencies, even in the

physics. For all frequencies in the audio range (e.g., for typical

sampling rates), such state variable growth cannot occur. Let's take

closer look at this phenomenon, first from a signal processing point

of view, and second from a physical point of view.

A Signal Processing Perspective on Repeated Mass-Spring Poles

Going back to the poles of the mass-spring system in Eq.![]() (F.39),

we see that, as the imaginary part of the two poles,

(F.39),

we see that, as the imaginary part of the two poles,

![]() , approach zero, they come together at

, approach zero, they come together at ![]() to create a

repeated pole. The same thing happens at

to create a

repeated pole. The same thing happens at

![]() since

both poles go to ``the point at infinity''.

since

both poles go to ``the point at infinity''.

It is a well known fact from linear systems theory that two poles at

the same point

![]() in the

in the ![]() plane can correspond to an

impulse-response component of the form

plane can correspond to an

impulse-response component of the form

![]() , in addition

to the component

, in addition

to the component

![]() produced by a single pole at

produced by a single pole at

![]() . In the discrete-time case, a double pole at

. In the discrete-time case, a double pole at ![]() can

give rise to an impulse-response component of the form

can

give rise to an impulse-response component of the form ![]() .

This is the fundamental source of the linearly growing internal states

of the wave digital sine oscillator at dc and

.

This is the fundamental source of the linearly growing internal states

of the wave digital sine oscillator at dc and ![]() . It is

interesting to note, however, that such modes are always

unobservable at any physical output such as the mass

force or spring force that is not actually linearly growing.

. It is

interesting to note, however, that such modes are always

unobservable at any physical output such as the mass

force or spring force that is not actually linearly growing.

Physical Perspective on Repeated Poles in the Mass-Spring System

In the physical system, dc and infinite frequency are in fact strange

cases. In the case of dc, for example, a nonzero constant force

implies that the mass ![]() is under constant acceleration. It is

therefore the case that its velocity is linearly growing. Our

simulation predicts this, since, using

Eq.

is under constant acceleration. It is

therefore the case that its velocity is linearly growing. Our

simulation predicts this, since, using

Eq.![]() (F.43) and Eq.

(F.43) and Eq.![]() (F.42),

(F.42),

![\begin{eqnarray*}

v_m(n) &=& \frac{f^{{+}}_m(n)}{m} - \frac{f^{{-}}_m(n)}{m}

=...

...m} \left[2(n+1) + 2n\right]x_0

= \frac{1}{m} (4 n x_0 + 2 x_0).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img5032.png)

The dc term ![]() is therefore accompanied by a linearly growing

term

is therefore accompanied by a linearly growing

term ![]() in the physical mass velocity. It is therefore

unavoidable that we have some means of producing an unbounded,

linearly growing output variable.

in the physical mass velocity. It is therefore

unavoidable that we have some means of producing an unbounded,

linearly growing output variable.

Mass-Spring Boundedness in Reality

To approach the limit of

![]() , we must either

take the spring constant

, we must either

take the spring constant ![]() to zero, or the mass

to zero, or the mass ![]() to infinity, or

both.

to infinity, or

both.

In the case of ![]() , the constant force must approach zero, and we

are left with at most a constant mass velocity in the limit (not a

linearly growing one, since there can be no dc force at the limit).

When the spring force reaches zero,

, the constant force must approach zero, and we

are left with at most a constant mass velocity in the limit (not a

linearly growing one, since there can be no dc force at the limit).

When the spring force reaches zero, ![]() , so that only zeros

will feed into the loop on the right in Fig.F.35, thus avoiding

a linearly growing velocity, as demanded by the physics. (A constant

velocity is free to circulate in the loop on the right, but the loop

on the left must be zeroed out in the limit.)

, so that only zeros

will feed into the loop on the right in Fig.F.35, thus avoiding

a linearly growing velocity, as demanded by the physics. (A constant

velocity is free to circulate in the loop on the right, but the loop

on the left must be zeroed out in the limit.)

In the case of

![]() , the mass becomes unaffected by the spring

force, so its final velocity must be zero. Otherwise, the attached

spring would keep compressing or stretching forever, and this would

take infinite energy. (Another way to arrive at this conclusion is to

note that the final kinetic energy of the mass would be

, the mass becomes unaffected by the spring

force, so its final velocity must be zero. Otherwise, the attached

spring would keep compressing or stretching forever, and this would

take infinite energy. (Another way to arrive at this conclusion is to

note that the final kinetic energy of the mass would be

![]() .) Since the total energy in an undriven mass-spring

oscillator is always constant, the infinite-mass limit must be

accompanied by a zero-velocity limit.F.6 This means the mass's

state variable

.) Since the total energy in an undriven mass-spring

oscillator is always constant, the infinite-mass limit must be

accompanied by a zero-velocity limit.F.6 This means the mass's

state variable ![]() in Fig.F.35 must be forced to zero in

the limit so that there will be no linearly growing solution at dc.

in Fig.F.35 must be forced to zero in

the limit so that there will be no linearly growing solution at dc.

In summary, when two or more system poles approach each other to form

a repeated pole, care must be taken to ensure that the limit is

approached in a physically meaningful way. In the case of the

mass-spring oscillator, for example, any change in the spring constant

![]() or mass

or mass ![]() must be accompanied by the physically appropriate

change in the state variables

must be accompanied by the physically appropriate

change in the state variables ![]() and/or

and/or ![]() . It is

obviously incorrect, for example, to suddenly set

. It is

obviously incorrect, for example, to suddenly set ![]() in the

simulation without simultaneously clearing the spring's state variable

in the

simulation without simultaneously clearing the spring's state variable

![]() , since the force across an infinitely compliant spring can

only be zero.

, since the force across an infinitely compliant spring can

only be zero.

Similar remarks apply to repeated poles corresponding to

![]() . In this case, the mass and spring basically change

places.

. In this case, the mass and spring basically change

places.

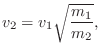

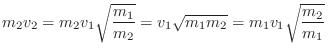

Energy-Preserving Parameter Changes (Mass-Spring Oscillator)

If the change in ![]() or

or ![]() is deemed to be ``internal'', that is,

involving no external interactions, the appropriate accompanying

change in the internal state variables is that which conserves

energy. For the mass and its velocity, for example, we must have

is deemed to be ``internal'', that is,

involving no external interactions, the appropriate accompanying

change in the internal state variables is that which conserves

energy. For the mass and its velocity, for example, we must have

If the spring constant ![]() is to change from

is to change from ![]() to

to ![]() , the

instantaneous spring displacement

, the

instantaneous spring displacement ![]() must satisfy

must satisfy

Exercises in Wave Digital Modeling

- Comparing digital and analog frequency formulas.

This first exercise verifies that the elementary ``tank circuit''

always resonates at exactly the frequency it should, according to the

bilinear transform frequency mapping

, where

, where  denotes ``analog frequency'' and

denotes ``analog frequency'' and  denotes ``digital frequency''.

denotes ``digital frequency''.

- Find the poles of Fig.F.35 in terms of

.

.

- Show that the resonance frequency is given by

where

denotes the sampling rate.

denotes the sampling rate.

- Recall that the mass-spring oscillator resonates at

. Relate these two resonance frequency formulas

via the analog-digital frequency map

. Relate these two resonance frequency formulas

via the analog-digital frequency map

.

.

- Show that the trig identity you discovered in this way is true.

I.e., show that

![$\displaystyle f_s \arccos\left[\frac{k-m}{k+m}\right] =

2f_s \arctan\left[\sqrt{\frac{m}{k}}\right].

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img5051.png)

- Find the poles of Fig.F.35 in terms of

Previous Section:

Adaptors for Wave Digital Elements