Early Musical Acoustics

All things which can be known have number; for it is not possible that without number anything can be either conceived or known.

-- Philolaus (ca. 400 BC)

Vibrating strings were studied by the Pythagoreans (6th-5th century BC). Pythagorus noticed that harmonics were produced by dividing the string length by whole numbers, and he was interested in understanding consonant pitch intervals in terms of simple ratios of string lengths. ``Harmony theory'' from the Pythagoreans was taught throughout the Middle Ages as one of the seven liberal arts: the quadrivium, consisting of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music (harmony theory); and the trivium, consisting of grammar, logic, and rhetoric [411]. The correspondence between musical pitch and frequency of physical vibration was not discovered until the seventeenth century [113].

It took until Galileo (1564-1642) to be free of the formulation of

Aristotle (384-322 BC) that all motion required an ongoing applied

force, thereby opening the way for modern differential equations of

motion. The ideas of Galileo were formalized and extended by Newton

(1642-1727), whose famous second law of motion ``![]() '' lies at the

foundation of essentially all classical mechanics and acoustics.

Newton's Principia (1686) describes sound as traveling

pressure pulses, and single-frequency sound waves were analyzed.

'' lies at the

foundation of essentially all classical mechanics and acoustics.

Newton's Principia (1686) describes sound as traveling

pressure pulses, and single-frequency sound waves were analyzed.

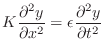

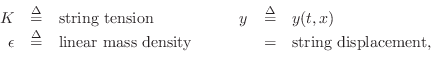

The first to publish a one-dimensional wave equation for the vibrating string was the applied mathematician Jean Le Rond d'Alembert (1717-1783) [100,103].A.1The 1D wave equation can be written as

where

where

Next Section:

History of Modal Expansion

Previous Section:

Other Instruments