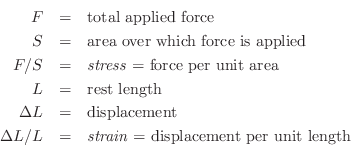

Properties of Elastic Solids

Young's Modulus

Young's modulus can be thought of as the spring constant

for solids. Consider an ideal rod (or bar) of length ![]() and

cross-sectional area

and

cross-sectional area ![]() . Suppose we apply a force

. Suppose we apply a force ![]() to the face of

area

to the face of

area ![]() , causing a displacement

, causing a displacement ![]() along the axis of the rod.

Then Young's modulus

along the axis of the rod.

Then Young's modulus ![]() is given by

is given by

For wood, Young's modulus ![]() is on the order of

is on the order of ![]() N/m

N/m![]() .

For aluminum, it is around

.

For aluminum, it is around ![]() (a bit higher than glass which is near

(a bit higher than glass which is near

![]() ), and structural steel has

), and structural steel has

![]() [180].

[180].

Young's Modulus as a Spring Constant

Recall (§B.1.3) that Hooke's Law defines a spring

constant ![]() as the applied force

as the applied force ![]() divided by the spring

displacement

divided by the spring

displacement ![]() , or

, or ![]() . An elastic solid can be viewed as a

bundle of ideal springs. Consider, for example, an ideal

bar (a rectangular solid in which one dimension, usually its

longest, is designated its length

. An elastic solid can be viewed as a

bundle of ideal springs. Consider, for example, an ideal

bar (a rectangular solid in which one dimension, usually its

longest, is designated its length ![]() ), and consider compression by

), and consider compression by

![]() along the length dimension. The length of each spring in

the bundle is the length of the bar, so that each spring constant

along the length dimension. The length of each spring in

the bundle is the length of the bar, so that each spring constant ![]() must be inversely proportional to

must be inversely proportional to ![]() ; in particular, each doubling of

length

; in particular, each doubling of

length ![]() doubles the length of each ``spring'' in the bundle, and

therefore halves its stiffness. As a result, it is useful to

normalize displacement

doubles the length of each ``spring'' in the bundle, and

therefore halves its stiffness. As a result, it is useful to

normalize displacement ![]() by length

by length ![]() and use relative

displacement

and use relative

displacement

![]() . We need displacement per unit length

because we have a constant spring compliance per unit length.

. We need displacement per unit length

because we have a constant spring compliance per unit length.

The number of springs in parallel is proportional to the

cross-sectional area ![]() of the bar. Therefore, the force applied to

each spring is proportional to the total applied force

of the bar. Therefore, the force applied to

each spring is proportional to the total applied force ![]() divided by

the cross-sectional area

divided by

the cross-sectional area ![]() . Thus, Hooke's law for each spring in the

bundle can be written

. Thus, Hooke's law for each spring in the

bundle can be written

We may say that Young's modulus is the Hooke's-law spring constant for the spring made from a specifically cut section of the solid material, cut to length 1 and cross-sectional area 1. The shape of the cross-sectional area does not matter since all displacement is assumed to be longitudinal in this model.

String Tension

The tension of a vibrating string is the force ![]() used

to stretch it. It is therefore directed along the axis of the string.

A force

used

to stretch it. It is therefore directed along the axis of the string.

A force ![]() must be applied at the endpoint on the right, and a force

must be applied at the endpoint on the right, and a force

![]() is applied at the endpoint on the left. Each point interior to

the string is pulled equally to the left and right,

i.e., the net force on an interior point is

is applied at the endpoint on the left. Each point interior to

the string is pulled equally to the left and right,

i.e., the net force on an interior point is

![]() . (A nonzero

force on a massless point would produce an infinite acceleration.)

. (A nonzero

force on a massless point would produce an infinite acceleration.)

If the cross-sectional area of the string is ![]() , then the tension is

given by the stress on the string times

, then the tension is

given by the stress on the string times ![]() .

.

Next Section:

Wave Equation for the Vibrating String

Previous Section:

Rigid-Body Dynamics