Center of Mass

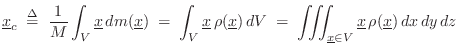

The center of mass (or centroid) of a rigid body is

found by averaging the spatial points of the body

![]() weighted by the mass

weighted by the mass ![]() of those points:B.12

of those points:B.12

A nice property of the center of mass is that gravity acts on a far-away object as if all its mass were concentrated at its center of mass. For this reason, the center of mass is often called the center of gravity.

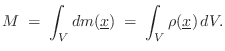

Linear Momentum of the Center of Mass

Consider a system of ![]() point-masses

point-masses ![]() , each traveling with

vector velocity

, each traveling with

vector velocity

![]() , and not necessarily rigidly attached to

each other. Then the total momentum of the system is

, and not necessarily rigidly attached to

each other. Then the total momentum of the system is

Thus, the momentum

![]() of any collection of masses

of any collection of masses ![]() (including rigid bodies) equals the total mass

(including rigid bodies) equals the total mass ![]() times the

velocity of the center-of-mass.

times the

velocity of the center-of-mass.

Whoops, No Angular Momentum!

The previous result might be surprising since we said at the outset that we were going to decompose the total momentum into a sum of linear plus angular momentum. Instead, we found that the total momentum is simply that of the center of mass, which means any angular momentum that might have been present just went away. (The center of mass is just a point that cannot rotate in a measurable way.) Angular momentum does not contribute to linear momentum, so it provides three new ``degrees of freedom'' (three new energy storage dimensions, in 3D space) that are ``missed'' when considering only linear momentum.

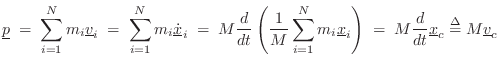

To obtain the desired decomposition of momentum into linear plus angular momentum, we will choose a fixed reference point in space (usually the center of mass) and then, with respect to that reference point, decompose an arbitrary mass-particle travel direction into the sum of two mutually orthogonal vector components: one will be the vector component pointing radially with respect to the fixed point (for the ``linear momentum'' component), and the other will be the vector component pointing tangentially with respect to the fixed point (for the ``angular momentum''), as shown in Fig.B.3. When the reference point is the center of mass, the resultant radial force component gives us the force on the center of mass, which creates linear momentum, while the net tangential component (times distance from the center-of-mass) give us a resultant torque about the reference point, which creates angular momentum. As we saw above, because the tangential force component does not contribute to linear momentum, we can simply sum the external force vectors and get the same result as summing their radial components. These topics will be discussed further below, after some elementary preliminaries.

![\includegraphics[width=1.5in]{eps/rigidbody}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2710.png) |

Next Section:

Translational Kinetic Energy

Previous Section:

Conservation of Momentum