The Simplest Lowpass Filter

Let's start with a very basic example of the generic problem at hand: understanding the effect of a digital filter on the spectrum of a digital signal. The purpose of this example is to provide motivation for the general theory discussed in later chapters.

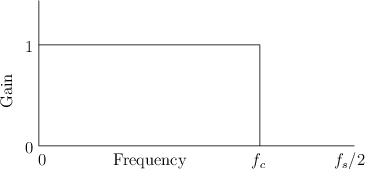

Our example is the simplest possible low-pass filter. A low-pass

filter is one which does not affect low frequencies and rejects high

frequencies. The function giving the gain of a filter at every

frequency is called the amplitude response (or magnitude

frequency response). The amplitude response of the ideal lowpass

filter is shown in Fig.1.1. Its gain is 1 in the

passband, which spans frequencies from 0 Hz to the cut-off

frequency ![]() Hz, and its gain is 0 in the stopband (all

frequencies above

Hz, and its gain is 0 in the stopband (all

frequencies above ![]() ). The output spectrum is obtained by

multiplying the input spectrum by the amplitude response of the

filter. In this way, signal components are eliminated (``stopped'')

at all frequencies above the cut-off frequency, while lower-frequency

components are ``passed'' unchanged to the output.

). The output spectrum is obtained by

multiplying the input spectrum by the amplitude response of the

filter. In this way, signal components are eliminated (``stopped'')

at all frequencies above the cut-off frequency, while lower-frequency

components are ``passed'' unchanged to the output.

Definition of the Simplest Low-Pass

The simplest (and by no means ideal) low-pass filter is given by the following difference equation:

where

It is important when working with spectra to be able to convert time

from sample-numbers, as in Eq.![]() (1.1) above, to seconds. A more

``physical'' way of writing the filter equation is

(1.1) above, to seconds. A more

``physical'' way of writing the filter equation is

To further our appreciation of this example, let's write a computer

subroutine to implement Eq.![]() (1.1). In the computer,

(1.1). In the computer, ![]() and

and

![]() are data arrays and

are data arrays and ![]() is an array index. Since sound files

may be larger than what the computer can hold in memory all at

once, we typically process the data in blocks of some reasonable

size. Therefore, the complete filtering operation consists of two

loops, one within the other. The outer loop fills the input array

is an array index. Since sound files

may be larger than what the computer can hold in memory all at

once, we typically process the data in blocks of some reasonable

size. Therefore, the complete filtering operation consists of two

loops, one within the other. The outer loop fills the input array ![]() and empties the output array

and empties the output array ![]() , while the inner loop does the actual

filtering of the

, while the inner loop does the actual

filtering of the ![]() array to produce

array to produce ![]() . Let

. Let ![]() denote the block

size (i.e., the number of samples to be processed on each iteration of

the outer loop). In the C programming language, the inner loop

of the subroutine might appear as shown in Fig.1.3. The outer

loop might read something like ``fill

denote the block

size (i.e., the number of samples to be processed on each iteration of

the outer loop). In the C programming language, the inner loop

of the subroutine might appear as shown in Fig.1.3. The outer

loop might read something like ``fill ![]() from the input file,''

``call simplp,'' and ``write out

from the input file,''

``call simplp,'' and ``write out ![]() .''

.''

/* C function implementing the simplest lowpass:

*

* y(n) = x(n) + x(n-1)

*

*/

double simplp (double *x, double *y,

int M, double xm1)

{

int n;

y[0] = x[0] + xm1;

for (n=1; n < M ; n++) {

y[n] = x[n] + x[n-1];

}

return x[M-1];

}

|

In this implementation, the first instance of ![]() is provided as

the procedure argument xm1. That way, both

is provided as

the procedure argument xm1. That way, both ![]() and

and ![]() can

have the same array bounds (

can

have the same array bounds (

![]() ). For convenience, the

value of xm1 appropriate for the next call to

simplp is returned as the procedure's value.

). For convenience, the

value of xm1 appropriate for the next call to

simplp is returned as the procedure's value.

We may call xm1 the filter's state. It is the current

``memory'' of the filter upon calling simplp. Since this

filter has only one sample of state, it is a first order

filter. When a filter is applied to successive blocks of a signal, it

is necessary to save the filter state after processing each block.

The filter state after processing block ![]() is then the starting state

for block

is then the starting state

for block ![]() .

.

Figure 1.4 illustrates a simple main program which calls simplp. The length 10 input signal x is processed in two blocks of length 5.

/* C main program for testing simplp */

main() {

double x[10] = {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10};

double y[10];

int i;

int N=10;

int M=N/2; /* block size */

double xm1 = 0;

xm1 = simplp(x, y, M, xm1);

xm1 = simplp(&x[M], &y[M], M, xm1);

for (i=0;i<N;i++) {

printf("x[%d]=%f\ty[%d]=%f\n",i,x[i],i,y[i]);

}

exit(0);

}

/* Output:

* x[0]=1.000000 y[0]=1.000000

* x[1]=2.000000 y[1]=3.000000

* x[2]=3.000000 y[2]=5.000000

* x[3]=4.000000 y[3]=7.000000

* x[4]=5.000000 y[4]=9.000000

* x[5]=6.000000 y[5]=11.000000

* x[6]=7.000000 y[6]=13.000000

* x[7]=8.000000 y[7]=15.000000

* x[8]=9.000000 y[8]=17.000000

* x[9]=10.000000 y[9]=19.000000

*/

|

You might suspect that since Eq.![]() (1.1) is the simplest possible

low-pass filter, it is also somehow the worst possible low-pass

filter. How bad is it? In what sense is it bad? How do we even know it

is a low-pass at all? The answers to these and related questions will

become apparent when we find the frequency response of this

filter.

(1.1) is the simplest possible

low-pass filter, it is also somehow the worst possible low-pass

filter. How bad is it? In what sense is it bad? How do we even know it

is a low-pass at all? The answers to these and related questions will

become apparent when we find the frequency response of this

filter.

Next Section:

Finding the Frequency Response

Previous Section:

Introduction