Background Fundamentals

Signal Representation and Notation

Below is a summary of various notational conventions used in digital signal processing for representing signals and spectra. For a more detailed presentation, see the elementary introduction to signal representation, sinusoids, and exponentials in [84].A.1

Units

In this book, time ![]() is always in physical units of seconds

(s), while time

is always in physical units of seconds

(s), while time ![]() or

or ![]() is in units of samples (counting

numbers having no physical units). Time

is in units of samples (counting

numbers having no physical units). Time ![]() is a continuous real

variable, while discrete-time in samples is integer-valued. The

physical time

is a continuous real

variable, while discrete-time in samples is integer-valued. The

physical time ![]() corresponding to time

corresponding to time ![]() in samples is given by

in samples is given by

For frequencies, we have two physical units: (1)

cycles per second and (2) radians per second. The

name for cycles per second is Hertz (Hz) (though in the past it

was cps). One cycle equals ![]() radians, which is 360

degrees (

radians, which is 360

degrees (![]() ). Therefore,

). Therefore, ![]() Hz is the same frequency as

Hz is the same frequency as ![]() radians per second (rad/s). It is easy to confuse the two because

both radians and cycles are pure numbers, so that both types of

frequency are in physical units of inverse seconds (s

radians per second (rad/s). It is easy to confuse the two because

both radians and cycles are pure numbers, so that both types of

frequency are in physical units of inverse seconds (s

![]() ).

).

For example, a periodic signal with a period of ![]() seconds has

a frequency of

seconds has

a frequency of ![]() Hz, and a radian frequency of

Hz, and a radian frequency of

![]() rad/s. The sampling rate,

rad/s. The sampling rate, ![]() , is the reciprocal of the

sampling period

, is the reciprocal of the

sampling period ![]() , i.e.,

, i.e.,

Sinusoids

The term sinusoid means a waveform of the type

Thus, a sinusoid may be defined as a cosine at amplitude

![$\displaystyle f(t) \isdef \frac{d}{dt} \theta(t) = \frac{d}{dt} \left[\omega t + \phi\right] = \omega

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1302.png)

Spectrum

In this book, we think of filters primarily in terms of their effect

on the spectrum of a signal. This is appropriate because the

ear (to a first approximation) converts the time-waveform at the

eardrum into a neurologically encoded spectrum. Intuitively, a

spectrum (a complex function of frequency ![]() ) gives the

amplitude and phase of the sinusoidal signal-component at frequency

) gives the

amplitude and phase of the sinusoidal signal-component at frequency

![]() . Mathematically, the spectrum of a signal

. Mathematically, the spectrum of a signal ![]() is the Fourier

transform of its time-waveform. Equivalently, the spectrum is the

z transform evaluated on the unit circle

is the Fourier

transform of its time-waveform. Equivalently, the spectrum is the

z transform evaluated on the unit circle

![]() . A detailed

introduction to spectrum analysis is given in

[84].A.2

. A detailed

introduction to spectrum analysis is given in

[84].A.2

We denote both the spectrum and the z transform of a signal by uppercase

letters. For example, if the time-waveform is denoted ![]() , its z transform

is called

, its z transform

is called ![]() and its spectrum is therefore

and its spectrum is therefore

![]() . The

time-waveform

. The

time-waveform ![]() is said to ``correspond'' to its z transform

is said to ``correspond'' to its z transform ![]() ,

meaning they are transform pairs. This correspondence is often denoted

,

meaning they are transform pairs. This correspondence is often denoted

![]() , or

, or

![]() . Both

the z transform and its special case, the (discrete-time) Fourier transform,

are said to transform from the time domain to the

frequency domain.

. Both

the z transform and its special case, the (discrete-time) Fourier transform,

are said to transform from the time domain to the

frequency domain.

We deal most often with discrete time ![]() (or simply

(or simply ![]() ) but

continuous frequency

) but

continuous frequency ![]() (or

(or

![]() ). This is because the

computer can represent only digital signals, and digital

time-waveforms are discrete in time but may have energy at any

frequency. On the other hand, if we were going to talk about FFTs

(Fast Fourier Transforms--efficient implementations of the Discrete

Fourier Transform, or DFT) [84], then we would have to

discretize the frequency variable also in order to represent spectra

inside the computer. In this book, however, we use spectra only for

conceptual insights into the perceptual effects of digital filtering;

therefore, we avoid discrete frequency for simplicity.

). This is because the

computer can represent only digital signals, and digital

time-waveforms are discrete in time but may have energy at any

frequency. On the other hand, if we were going to talk about FFTs

(Fast Fourier Transforms--efficient implementations of the Discrete

Fourier Transform, or DFT) [84], then we would have to

discretize the frequency variable also in order to represent spectra

inside the computer. In this book, however, we use spectra only for

conceptual insights into the perceptual effects of digital filtering;

therefore, we avoid discrete frequency for simplicity.

When we wish to consider an entire signal as a ``thing in itself,'' we

write ![]() , meaning the whole time-waveform (

, meaning the whole time-waveform (![]() for all

for all

![]() ), or

), or ![]() , to mean the entire spectrum taken as a whole.

Imagine, for example, that we have plotted

, to mean the entire spectrum taken as a whole.

Imagine, for example, that we have plotted ![]() on a strip of paper

that is infinitely long. Then

on a strip of paper

that is infinitely long. Then ![]() refers to the complete

picture, while

refers to the complete

picture, while ![]() refers to the

refers to the ![]() th sample point on the plot.

th sample point on the plot.

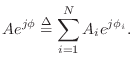

Complex and Trigonometric Identities

This section gives a summary of some of the more useful mathematical identities for complex numbers and trigonometry in the context of digital filter analysis. For many more, see handbooks of mathematical functions such as Abramowitz and Stegun [2].

The symbol ![]() means ``is defined as'';

means ``is defined as''; ![]() stands for a complex

number; and

stands for a complex

number; and ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() stand for real numbers. The

quantity

stand for real numbers. The

quantity ![]() is used below to denote

is used below to denote

![]() .

.

Complex Numbers

The Exponential Function

Trigonometric Identities

Trigonometric Identities, Continued

Half-Angle Tangent Identities

A Sum of Sinusoids at the

Same Frequency is Another

Sinusoid at that Frequency

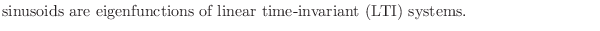

It is an important and fundamental fact that a sum of sinusoids at the same frequency, but different phase and amplitude, can always be expressed as a single sinusoid at that frequency with some resultant phase and amplitude. An important implication, for example, is that

That is, if a sinusoid is input to an LTI system, the output will be a sinusoid at the same frequency, but possibly altered in amplitude and phase. This follows because the output of every LTI system can be expressed as a linear combination of delayed copies of the input signal. In this section, we derive this important result for the general case of

Proof Using Trigonometry

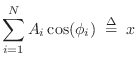

We want to show it is always possible to solve

for

| (A.3) |

Applying this expansion to Eq.

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\left[A\cos(\phi)\right]\cos(\omega t)

&-&\left[A\sin(\phi)\ri...

...a t)

- \left[\sum_{i=1}^N A_i\sin(\phi_i)\right]\sin(\omega t).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1320.png)

Equating coefficients gives

where

which has a unique solution for any values of ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

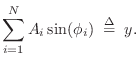

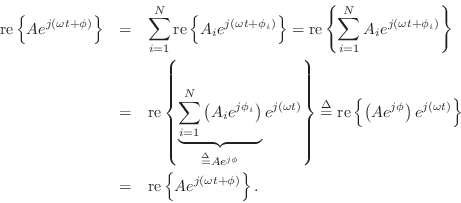

Proof Using Complex Variables

To show by means of phasor analysis that Eq.![]() (A.2) always has a solution, we can express each component sinusoid as

(A.2) always has a solution, we can express each component sinusoid as

Thus, equality holds when we define

Since

As is often the case, we see that the use of Euler's identity and complex analysis gives a simplified algebraic proof which replaces a proof based on trigonometric identities.

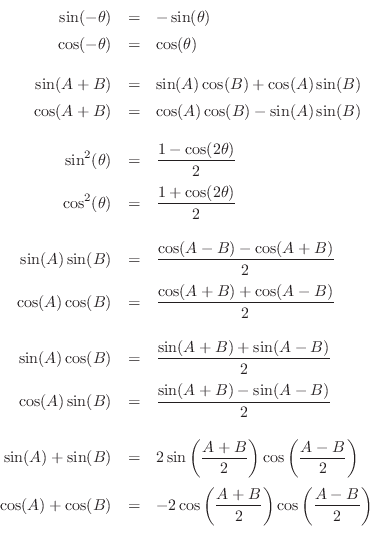

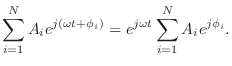

Phasor Analysis: Factoring a Complex Sinusoid into Phasor Times Carrier

The heart of the preceding proof was the algebraic manipulation

For an arbitrary sinusoid having amplitude ![]() , phase

, phase ![]() , and

radian frequency

, and

radian frequency ![]() , we have

, we have

Next Section:

Elementary Audio Digital Filters

Previous Section:

Conclusion