Symmetry

In the previous section, we found

![]() when

when ![]() is

real. This fact is of high practical importance. It says that the

spectrum of every real signal is Hermitian.

Due to this symmetry, we may discard all negative-frequency spectral

samples of a real signal and regenerate them later if needed from the

positive-frequency samples. Also, spectral plots of real signals are

normally displayed only for positive frequencies; e.g., spectra of

sampled signals are normally plotted over the range 0 Hz to

is

real. This fact is of high practical importance. It says that the

spectrum of every real signal is Hermitian.

Due to this symmetry, we may discard all negative-frequency spectral

samples of a real signal and regenerate them later if needed from the

positive-frequency samples. Also, spectral plots of real signals are

normally displayed only for positive frequencies; e.g., spectra of

sampled signals are normally plotted over the range 0 Hz to ![]() Hz. On the other hand, the spectrum of a complex signal must

be shown, in general, from

Hz. On the other hand, the spectrum of a complex signal must

be shown, in general, from ![]() to

to ![]() (or from 0 to

(or from 0 to ![]() ),

since the positive and negative frequency components of a complex

signal are independent.

),

since the positive and negative frequency components of a complex

signal are independent.

Recall from §7.3 that a signal ![]() is said to be

even if

is said to be

even if

![]() , and odd if

, and odd if

![]() . Below

are are Fourier theorems pertaining to even and odd signals and/or

spectra.

. Below

are are Fourier theorems pertaining to even and odd signals and/or

spectra.

Theorem: If

![]() , then

re

, then

re![]() is even and

im

is even and

im![]() is odd.

is odd.

Proof: This follows immediately from the conjugate symmetry of ![]() for real signals

for real signals

![]() .

.

Theorem: If

![]() ,

,

![]() is even and

is even and ![]() is odd.

is odd.

Proof: This follows immediately from the conjugate symmetry of ![]() expressed

in polar form

expressed

in polar form

![]() .

.

The conjugate symmetry of spectra of real signals is perhaps the most important symmetry theorem. However, there are a couple more we can readily show:

Theorem: An even signal has an even transform:

Proof:

Express ![]() in terms of its real and imaginary parts by

in terms of its real and imaginary parts by

![]() . Note that for a complex signal

. Note that for a complex signal ![]() to be even, both its real and

imaginary parts must be even. Then

to be even, both its real and

imaginary parts must be even. Then

Let even

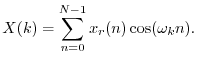

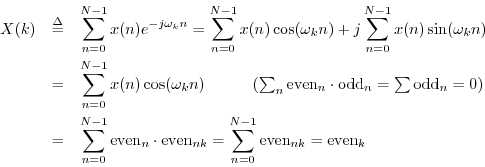

![\begin{eqnarray*}

X(k)&=&\sum_{n=0}^{N-1}\mbox{even}_n\cdot\mbox{even}_{nk}

+ ...

...10pt]

&=& \mbox{even}_k + j \cdot \mbox{even}_k = \mbox{even}_k.

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img1356.png)

Theorem: A real even signal has a real even transform:

Proof: This follows immediately from setting ![]() in the preceding

proof. From Eq.

in the preceding

proof. From Eq.![]() (7.5), we are left with

(7.5), we are left with

Instead of adapting the previous proof, we can show it directly:

Definition: A signal with a real spectrum (such as any real, even signal)

is often called a zero phase signal. However, note that when

the spectrum goes negative (which it can), the phase is really

![]() , not 0. When a real spectrum is positive at dc (i.e.,

, not 0. When a real spectrum is positive at dc (i.e.,

![]() ), it is then truly zero-phase over at least some band

containing dc (up to the first zero-crossing in frequency). When the

phase switches between 0 and

), it is then truly zero-phase over at least some band

containing dc (up to the first zero-crossing in frequency). When the

phase switches between 0 and ![]() at the zero-crossings of the

(real) spectrum, the spectrum oscillates between being zero phase and

``constant phase''. We can say that all real spectra are

piecewise constant-phase spectra, where the two constant values

are 0 and

at the zero-crossings of the

(real) spectrum, the spectrum oscillates between being zero phase and

``constant phase''. We can say that all real spectra are

piecewise constant-phase spectra, where the two constant values

are 0 and ![]() (or

(or ![]() , which is the same phase as

, which is the same phase as ![]() ). In

practice, such zero-crossings typically occur at low magnitude, such

as in the ``side-lobes'' of the DTFT of a ``zero-centered symmetric

window'' used for spectrum analysis (see Chapter 8 and Book IV

[70]).

). In

practice, such zero-crossings typically occur at low magnitude, such

as in the ``side-lobes'' of the DTFT of a ``zero-centered symmetric

window'' used for spectrum analysis (see Chapter 8 and Book IV

[70]).

Next Section:

Shift Theorem

Previous Section:

Conjugation and Reversal

![$\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}[x_r(n)+jx_i(n)] \cos(\omega_k n) - j [x_r(n)+jx_i(n)] \sin(\omega_k n)$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img1348.png)

![$\displaystyle \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}[x_r(n)\cos(\omega_k n) + x_i(n)\sin(\omega_k n)]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img1349.png)