Normalized Scattering Junctions

Using (C.53) to convert to normalized waves

![]() , the

Kelly-Lochbaum junction (C.60) becomes

, the

Kelly-Lochbaum junction (C.60) becomes

as diagrammed in Fig.C.22. This is called the normalized scattering junction [297], although a more precise term would be the ``normalized-wave scattering junction.''

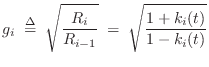

It is interesting to define

![]() , always

possible for passive junctions since

, always

possible for passive junctions since

![]() , and note that

the normalized scattering junction is equivalent to a 2D rotation:

, and note that

the normalized scattering junction is equivalent to a 2D rotation:

where, for conciseness of notation, the time-invariant case is written.

While it appears that scattering of normalized waves at a two-port junction requires four multiplies and two additions, it is possible to convert this to three multiplies and three additions using a two-multiply ``transformer'' to power-normalize an ordinary one-multiply junction [432].

The transformer is a lossless two-port defined by [136]

The transformer can be thought of as a device which steps the wave impedance to a new value without scattering; instead, the traveling signal power is redistributed among the force and velocity wave variables to satisfy the fundamental relations

as can be quickly derived by requiring

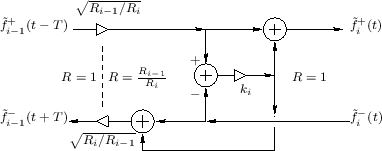

Figure C.23 illustrates a three-multiply

normalized-wave scattering junction [432]. The impedance of

all waveguides (bidirectional delay lines) may be taken to be ![]() .

Scattering junctions may then be implemented as a denormalizing

transformer

.

Scattering junctions may then be implemented as a denormalizing

transformer

![]() , a one-multiply scattering junction

, a one-multiply scattering junction

![]() , and a renormalizing transformer

, and a renormalizing transformer

![]() . Either

transformer may be commuted with the junction and combined with the

other transformer to give a three-multiply normalized-wave scattering

junction. (The transformers are combined on the left in

Fig.C.23).

. Either

transformer may be commuted with the junction and combined with the

other transformer to give a three-multiply normalized-wave scattering

junction. (The transformers are combined on the left in

Fig.C.23).

In slightly more detail, a transformer

![]() steps the wave

impedance (left-to-right) from

steps the wave

impedance (left-to-right) from ![]() to

to ![]() . Equivalently, the

normalized force-wave

. Equivalently, the

normalized force-wave

![]() is converted unnormalized form

is converted unnormalized form

![]() . Next there is a physical scattering from impedance

. Next there is a physical scattering from impedance

![]() to

to ![]() (reflection coefficient

(reflection coefficient

![]() ). The outgoing wave to the right is

then normalized by transformer

). The outgoing wave to the right is

then normalized by transformer

![]() to return the wave

impedance back to

to return the wave

impedance back to ![]() for wave propagation within a normalized-wave

delay line to the right. Finally, the right transformer is commuted

left and combined with the left transformer to reduce total

computational complexity to one multiply and three adds.

for wave propagation within a normalized-wave

delay line to the right. Finally, the right transformer is commuted

left and combined with the left transformer to reduce total

computational complexity to one multiply and three adds.

It is important to notice that transformer-normalized junctions may

have a large dynamic range in practice. For example, if

![]() , then Eq.

, then Eq.![]() (C.69) shows that the

transformer coefficients may become as large as

(C.69) shows that the

transformer coefficients may become as large as

![]() . If

. If ![]() is the ``machine epsilon,'' i.e.,

is the ``machine epsilon,'' i.e.,

![]() for typical

for typical ![]() -bit two's complement arithmetic normalized

to lie in

-bit two's complement arithmetic normalized

to lie in ![]() , then the dynamic range of the transformer

coefficients is bounded by

, then the dynamic range of the transformer

coefficients is bounded by

![]() . Thus, while

transformer-normalized junctions trade a multiply for an add, they

require up to

. Thus, while

transformer-normalized junctions trade a multiply for an add, they

require up to ![]() % more bits of dynamic range within the junction

adders. On the other hand, it is very nice to have normalized waves

(unit wave impedance) throughout the digital waveguide network,

thereby limiting the required dynamic range to root physical power in

all propagation paths.

% more bits of dynamic range within the junction

adders. On the other hand, it is very nice to have normalized waves

(unit wave impedance) throughout the digital waveguide network,

thereby limiting the required dynamic range to root physical power in

all propagation paths.

Next Section:

Junction Passivity

Previous Section:

One-Multiply Scattering Junctions

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/scatnlf}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img3623.png)