An Easier Way

We derived the frequency response above using trig identities in order to minimize the mathematical level involved. However, it turns out it is actually easier, though more advanced, to use complex numbers for this purpose. To do this, we need Euler's identity:

where

Complex Sinusoids

Using Euler's identity to represent sinusoids, we have

when time

Any function of the form

![]() or

or

![]() will henceforth be called a complex

sinusoid.2.3 We will

see that it is easier to manipulate both sine and

cosine simultaneously in this form than it is to deal with

either

sine or cosine separately. One may even take the

point of view that

will henceforth be called a complex

sinusoid.2.3 We will

see that it is easier to manipulate both sine and

cosine simultaneously in this form than it is to deal with

either

sine or cosine separately. One may even take the

point of view that

![]() is simpler and more

fundamental than

is simpler and more

fundamental than

![]() or

or

![]() , as evidenced by

the following identities (which are immediate consequences of Euler's

identity,

Eq.

, as evidenced by

the following identities (which are immediate consequences of Euler's

identity,

Eq.![]() (1.8)):

(1.8)):

Thus, sine and cosine may each be regarded as a combination of two complex sinusoids. Another reason for the success of the complex sinusoid is that we will be concerned only with real linear operations on signals. This means that

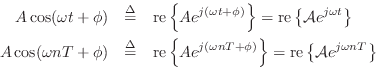

Complex Amplitude

Note that the amplitude ![]() and phase

and phase ![]() can be viewed as the

magnitude and angle of a single complex number

can be viewed as the

magnitude and angle of a single complex number

Phasor Notation

The complex amplitude

![]() is also defined as the

phasor associated with any sinusoid having amplitude

is also defined as the

phasor associated with any sinusoid having amplitude ![]() and

phase

and

phase ![]() . The term ``phasor'' is more general than ``complex

amplitude'', however, because it also applies to the corresponding

real sinusoid given by the real part of Equations (1.9-1.10).

In other words, the real sinusoids

. The term ``phasor'' is more general than ``complex

amplitude'', however, because it also applies to the corresponding

real sinusoid given by the real part of Equations (1.9-1.10).

In other words, the real sinusoids

![]() and

and

![]() may be expressed as

may be expressed as

and ![]() is the associated phasor in each case. Thus, we say that

the phasor representation of

is the associated phasor in each case. Thus, we say that

the phasor representation of

![]() is

is

![]() . Phasor analysis is

often used to analyze linear time-invariant systems such as analog

electrical circuits.

. Phasor analysis is

often used to analyze linear time-invariant systems such as analog

electrical circuits.

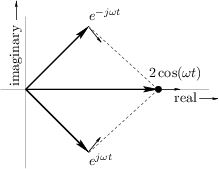

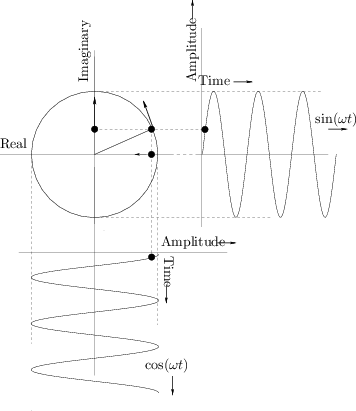

Plotting Complex Sinusoids as Circular Motion

Figure 1.8 shows Euler's relation graphically as it applies to

sinusoids. A point traveling with uniform velocity around a circle

with radius 1 may be represented by

![]() in

the complex plane, where

in

the complex plane, where ![]() is time and

is time and ![]() is the number of

revolutions per second. The projection of this motion onto the

horizontal (real) axis is

is the number of

revolutions per second. The projection of this motion onto the

horizontal (real) axis is

![]() , and the projection onto

the vertical (imaginary) axis is

, and the projection onto

the vertical (imaginary) axis is

![]() . For

discrete-time circular motion, replace

. For

discrete-time circular motion, replace ![]() by

by ![]() to get

to get

![]() which may be interpreted as a

point which jumps an arc length

which may be interpreted as a

point which jumps an arc length

![]() radians along the circle

each sampling instant.

radians along the circle

each sampling instant.

|

For circular motion to ensue, the sinusoidal motions must be at the same frequency, one-quarter cycle out of phase, and perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other. (With phase differences other than one-quarter cycle, the motion is generally elliptical.)

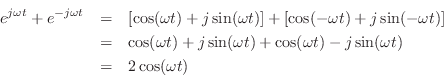

The converse of this is also illuminating. Take the usual circular

motion

![]() which spins counterclockwise along the unit

circle as

which spins counterclockwise along the unit

circle as ![]() increases, and add to it a similar but clockwise

circular motion

increases, and add to it a similar but clockwise

circular motion

![]() . This is shown in

Fig.1.9. Next apply Euler's identity to get

. This is shown in

Fig.1.9. Next apply Euler's identity to get

Thus,

This statement is a graphical or geometric interpretation of Eq.

We call

![]() a

positive-frequency sinusoidal component

when

a

positive-frequency sinusoidal component

when

![]() , and

, and

![]() is the

corresponding negative-frequency component. Note that both

sine and cosine signals have equal-amplitude positive- and

negative-frequency components (see also [84,53]). This

happens to be true of every real signal (i.e., non-complex). To

see this, recall that every signal can be represented as a sum of

complex sinusoids at various frequencies (its Fourier

expansion). For the signal to be real, every positive-frequency

complex sinusoid must be summed with a negative-frequency sinusoid of

equal amplitude. In other words, any counterclockwise circular motion

must be matched by an equal and opposite clockwise circular motion in

order that the imaginary parts always cancel to yield a real signal

(see Fig.1.9). Thus, a real signal always has a magnitude

spectrum which is symmetric about 0 Hz. Fourier symmetries such as

this are developed more completely in [84].

is the

corresponding negative-frequency component. Note that both

sine and cosine signals have equal-amplitude positive- and

negative-frequency components (see also [84,53]). This

happens to be true of every real signal (i.e., non-complex). To

see this, recall that every signal can be represented as a sum of

complex sinusoids at various frequencies (its Fourier

expansion). For the signal to be real, every positive-frequency

complex sinusoid must be summed with a negative-frequency sinusoid of

equal amplitude. In other words, any counterclockwise circular motion

must be matched by an equal and opposite clockwise circular motion in

order that the imaginary parts always cancel to yield a real signal

(see Fig.1.9). Thus, a real signal always has a magnitude

spectrum which is symmetric about 0 Hz. Fourier symmetries such as

this are developed more completely in [84].

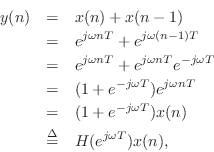

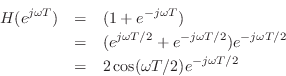

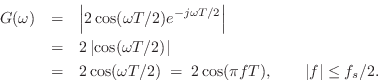

Rederiving the Frequency Response

Let's repeat the mathematical sine-wave analysis of the simplest

low-pass filter, but this time using a complex sinusoid instead of a

real one. Thus, we will test the filter's response at frequency ![]() by setting its input to

by setting its input to

Using the normal rules for manipulating exponents, we find that the

output of the simple low-pass filter in response to the complex

sinusoid at frequency

![]() Hz is given by

Hz is given by

where we have defined

![]() , which we

will show is in fact the frequency response of this filter at

frequency

, which we

will show is in fact the frequency response of this filter at

frequency ![]() . This derivation is clearly easier than the

trigonometry approach. What may be puzzling at first, however, is

that the filter is expressed as a frequency-dependent complex

multiply (when the input signal is a complex sinusoid). What does

this mean? Well, the theory we are blindly trusting at this point

says it must somehow mean a gain scaling and a phase shift. This is

true and easy to see once the complex filter gain is expressed in

polar form,

. This derivation is clearly easier than the

trigonometry approach. What may be puzzling at first, however, is

that the filter is expressed as a frequency-dependent complex

multiply (when the input signal is a complex sinusoid). What does

this mean? Well, the theory we are blindly trusting at this point

says it must somehow mean a gain scaling and a phase shift. This is

true and easy to see once the complex filter gain is expressed in

polar form,

It is now easy to see that

and

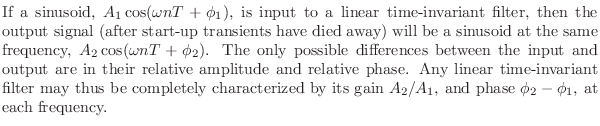

It deserves to be emphasized that all a linear time-invariant filter

can do to a sinusoid is scale its amplitude and change

its phase. Since a sinusoid is completely determined by its amplitude

![]() , frequency

, frequency ![]() , and phase

, and phase ![]() , the constraint on the filter is

that the output must also be a sinusoid, and furthermore it must be at

the same frequency as the input sinusoid. More explicitly:

, the constraint on the filter is

that the output must also be a sinusoid, and furthermore it must be at

the same frequency as the input sinusoid. More explicitly:

Mathematically, a sinusoid has no beginning and no end, so there really are no start-up transients in the theoretical setting. However, in practice, we must approximate eternal sinusoids with finite-time sinusoids whose starting time was so long ago that the filter output is essentially the same as if the input had been applied forever.

Tying it all together, the general output of a linear time-invariant filter with a complex sinusoidal input may be expressed as

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(n) &=& (\textit{Complex Filter Gain}) \;\textit{times}\;\, (...

...ith Radius $[G(\omega)A]$\ and Phase $[\phi + \Theta(\omega)]$}.

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img241.png)

Next Section:

Summary

Previous Section:

Finding the Frequency Response