Group Delay

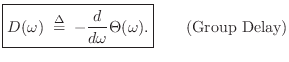

A more commonly encountered representation of filter phase response is called the group delay, defined by

An example of a linear phase response is that of the simplest lowpass

filter,

![]() . Thus, both the phase delay and the group

delay of the simplest lowpass filter are equal to half a sample at

every frequency.

. Thus, both the phase delay and the group

delay of the simplest lowpass filter are equal to half a sample at

every frequency.

For any reasonably smooth phase function, the group delay ![]() may be interpreted as the time delay of the amplitude envelope

of a sinusoid at frequency

may be interpreted as the time delay of the amplitude envelope

of a sinusoid at frequency ![]() [63]. The bandwidth of

the amplitude envelope in this interpretation must be restricted to a

frequency interval over which the phase response is approximately

linear. We derive this result in the next subsection.

[63]. The bandwidth of

the amplitude envelope in this interpretation must be restricted to a

frequency interval over which the phase response is approximately

linear. We derive this result in the next subsection.

Thus, the name ``group delay'' for ![]() refers to the fact that

it specifies the delay experienced by a narrow-band ``group'' of

sinusoidal components which have frequencies within a narrow frequency

interval about

refers to the fact that

it specifies the delay experienced by a narrow-band ``group'' of

sinusoidal components which have frequencies within a narrow frequency

interval about ![]() . The width of this interval is limited to

that over which

. The width of this interval is limited to

that over which ![]() is approximately constant.

is approximately constant.

Derivation of Group Delay as Modulation Delay

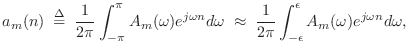

Suppose we write a narrowband signal centered at frequency ![]() as

as

where

Using the above frequency-domain expansion of ![]() ,

, ![]() can be

written as

can be

written as

![$\displaystyle x(n) \eqsp a_m(n) e^{j\omega_c n} \eqsp

\left[\frac{1}{2\pi} \int_{-\epsilon}^{\epsilon} A_m(\omega)e^{j\omega n} d\omega\right] e^{j\omega_c n},

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img908.png)

Assuming the phase response

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y_\omega(n)

&=& \left[G(\omega_c+\omega)A_m(\omega)\right]

e^...

...\right]

e^{j\omega[n-D(\omega_c)]} e^{j\omega_c[n-P(\omega_c)]},

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img916.png)

where we also used the definition of phase delay,

![]() , in the last step. In this expression we

can already see that the carrier sinusoid is delayed by the phase

delay, while the amplitude-envelope frequency-component is delayed by

the group delay. Integrating over

, in the last step. In this expression we

can already see that the carrier sinusoid is delayed by the phase

delay, while the amplitude-envelope frequency-component is delayed by

the group delay. Integrating over ![]() to recombine the

sinusoidal components (i.e., using a Fourier superposition integral for

to recombine the

sinusoidal components (i.e., using a Fourier superposition integral for

![]() ) gives

) gives

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(n) &=& \frac{1}{2\pi}\int_{\omega} y_\omega(n) d\omega \\

&...

...)]}\\

&=& a^f[n-D(\omega_c)] \cdot e^{j\omega_c[n-P(\omega_c)]}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img918.png)

where ![]() denotes a zero-phase filtering of the amplitude

envelope

denotes a zero-phase filtering of the amplitude

envelope ![]() by

by

![]() . We see that the amplitude

modulation is delayed by

. We see that the amplitude

modulation is delayed by

![]() while the carrier wave is

delayed by

while the carrier wave is

delayed by

![]() .

.

We have shown that, for narrowband signals expressed as in

Eq.![]() (7.6) as a modulation envelope times a sinusoidal carrier, the

carrier wave is delayed by the filter phase delay, while the

modulation is delayed by the filter group delay, provided that the

filter phase response is approximately linear over the narrowband

frequency interval.

(7.6) as a modulation envelope times a sinusoidal carrier, the

carrier wave is delayed by the filter phase delay, while the

modulation is delayed by the filter group delay, provided that the

filter phase response is approximately linear over the narrowband

frequency interval.

Next Section:

Group Delay Examples in Matlab

Previous Section:

Phase Unwrapping