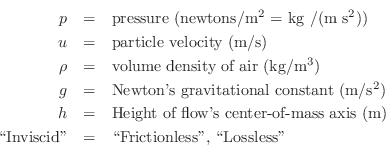

Properties of Gases

Particle Velocity of a Gas

The particle velocity of a gas flow at any point can be defined as the average velocity (in meters per second, m/s) of the air molecules passing through a plane cutting orthogonal to the flow. The term ``velocity'' in this book, when referring to air, means ``particle velocity.''

It is common in acoustics to denote particle velocity by lower-case

![]() .

.

Volume Velocity of a Gas

The volume velocity ![]() of a gas flow is defined as particle

velocity

of a gas flow is defined as particle

velocity ![]() times the cross-sectional area

times the cross-sectional area ![]() of the flow, or

of the flow, or

When a flow is confined within an enclosed channel, as it is in an

acoustic tube, volume velocity is conserved when the tube

changes cross-sectional area, assuming the density ![]() remains

constant. This follows directly from conservation of mass in a flow:

The total mass passing a given point

remains

constant. This follows directly from conservation of mass in a flow:

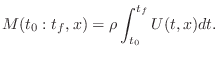

The total mass passing a given point ![]() along the flow is given by

the mass density

along the flow is given by

the mass density ![]() times the integral of the volume volume

velocity at that point, or

times the integral of the volume volume

velocity at that point, or

As a simple example, consider a constant flow through two cylindrical

acoustic tube sections having cross-sectional areas ![]() and

and ![]() ,

respectively. If the particle velocity in cylinder 1 is

,

respectively. If the particle velocity in cylinder 1 is ![]() , then

the particle velocity in cylinder 2 may be found by solving

, then

the particle velocity in cylinder 2 may be found by solving

It is common in the field of acoustics to denote volume velocity by an

upper-case ![]() . Thus, for the two-cylinder acoustic tube example above,

we would define

. Thus, for the two-cylinder acoustic tube example above,

we would define

![]() and

and

![]() , so that

, so that

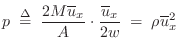

Pressure is Confined Kinetic Energy

According the kinetic theory of ideal gases [180], air pressure can be defined as the average momentum transfer per unit area per unit time due to molecular collisions between a confined gas and its boundary. Using Newton's second law, this pressure can be shown to be given by one third of the average kinetic energy of molecules in the gas.

Proof: This is a classical result from the kinetic theory of gases

[180]. Let ![]() be the total mass of a gas

confined to a rectangular volume

be the total mass of a gas

confined to a rectangular volume ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the area of

one side and

is the area of

one side and ![]() the distance to the opposite side. Let

the distance to the opposite side. Let

![]() denote the average molecule velocity in the

denote the average molecule velocity in the ![]() direction. Then the

total net molecular momentum in the

direction. Then the

total net molecular momentum in the ![]() direction is given by

direction is given by

![]() . Suppose the momentum

. Suppose the momentum

![]() is directed

against a face of area

is directed

against a face of area ![]() . A rigid-wall elastic collision by a mass

. A rigid-wall elastic collision by a mass

![]() traveling into the wall at velocity

traveling into the wall at velocity

![]() imparts a momentum of

magnitude

imparts a momentum of

magnitude

![]() to the wall (because the momentum of the mass is

changed from

to the wall (because the momentum of the mass is

changed from

![]() to

to

![]() , and momentum is conserved).

The average momentum-transfer per unit area is therefore

, and momentum is conserved).

The average momentum-transfer per unit area is therefore

![]() at any instant in time. To obtain the definition of pressure, we need

only multiply by the average collision rate, which is given by

at any instant in time. To obtain the definition of pressure, we need

only multiply by the average collision rate, which is given by

![]() . That is, the average

. That is, the average ![]() -velocity divided by the

round-trip distance along the

-velocity divided by the

round-trip distance along the ![]() dimension gives the collision rate

at either wall bounding the

dimension gives the collision rate

at either wall bounding the ![]() dimension. Thus, we obtain

dimension. Thus, we obtain

Bernoulli Equation

In an ideal inviscid, incompressible flow, we have, by conservation of energy,

This basic energy conservation law was published in 1738 by Daniel Bernoulli in his classic work Hydrodynamica.

From §B.7.3, we have that the pressure of a gas is

proportional to the average kinetic energy of the molecules making up

the gas. Therefore, when a gas flows at a constant height ![]() , some

of its ``pressure kinetic energy'' must be given to the kinetic energy

of the flow as a whole. If the mean height of the flow changes, then

kinetic energy trades with potential energy as well.

, some

of its ``pressure kinetic energy'' must be given to the kinetic energy

of the flow as a whole. If the mean height of the flow changes, then

kinetic energy trades with potential energy as well.

Bernoulli Effect

The Bernoulli effect provides that, when a gas such as air flows, its pressure drops. This is the basis for how aircraft wings work: The cross-sectional shape of the wing, called an aerofoil (or airfoil), forces air to follow a longer path over the top of the wing, thereby speeding it up and creating a net upward force called lift.

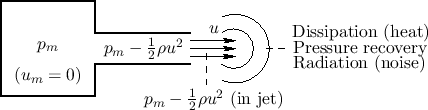

Figure B.8 illustrates the Bernoulli effect for the case

of a reservoir at constant pressure ![]() (``mouth pressure'') driving

an acoustic tube. Any flow inside the ``mouth'' is neglected. Within the

acoustic channel, there is a flow with constant particle velocity

(``mouth pressure'') driving

an acoustic tube. Any flow inside the ``mouth'' is neglected. Within the

acoustic channel, there is a flow with constant particle velocity ![]() .

To conserve energy, the pressure within the acoustic channel must drop

down to

.

To conserve energy, the pressure within the acoustic channel must drop

down to

![]() . That is, the flow kinetic energy subtracts

from the pressure kinetic energy within the channel.

. That is, the flow kinetic energy subtracts

from the pressure kinetic energy within the channel.

For a more detailed derivation of the Bernoulli effect, see, e.g., [179]. Further discussion of its relevance in musical acoustics is given in [144,197].

Air Jets

Referring again to Fig.B.8, the gas flow exiting the acoustic tube is shown as forming a jet. The jet ``carries its own pressure'' until it dissipates in some form, such as any combination of the following:

- heat (now allowing for ``friction'' in the flow),

- vortices (angular momentum),

- radiation (sound waves), or

- pressure recovery.

For a summary of more advanced aeroacoustics, including consideration of vortices, see [196]. In addition, basic textbooks on fluid mechanics are relevant [171].

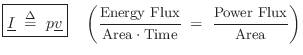

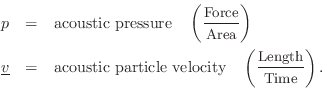

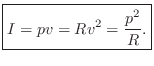

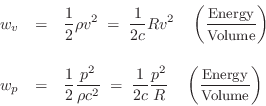

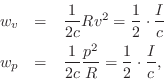

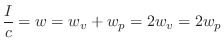

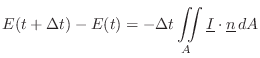

Acoustic Intensity

Acoustic intensity may be defined by

For a plane traveling wave, we have

Therefore, in a plane wave,

Acoustic Energy Density

The two forms of energy in a wave are kinetic and

potential. Denoting them at a particular time ![]() and position

and position

![]() by

by

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively, we can write them in

terms of velocity

, respectively, we can write them in

terms of velocity ![]() and wave impedance

and wave impedance ![]() as follows:

as follows:

More specifically, ![]() and

and ![]() may be called the acoustic kinetic

energy density and the acoustic potential energy density, respectively.

may be called the acoustic kinetic

energy density and the acoustic potential energy density, respectively.

At each point in a plane wave, we have

![]() (pressure equals wave-impedance times velocity), and so

(pressure equals wave-impedance times velocity), and so

where

![]() denotes the acoustic

intensity (pressure times velocity) at time

denotes the acoustic

intensity (pressure times velocity) at time ![]() and position

and position

![]() .

Thus, half of the acoustic intensity

.

Thus, half of the acoustic intensity ![]() in a plane wave is kinetic,

and the other half is potential:B.30

in a plane wave is kinetic,

and the other half is potential:B.30

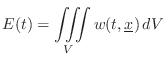

Energy Decay through Lossy Boundaries

Since the acoustic energy density ![]() is the energy per unit

volume in a 3D sound field, it follows that the total energy of the

field is given by integrating over the volume:

is the energy per unit

volume in a 3D sound field, it follows that the total energy of the

field is given by integrating over the volume:

Sabine's theory of acoustic energy decay in reverberant room impulse responses can be derived using this conservation relation as a starting point.

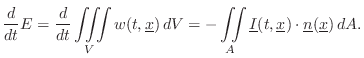

Ideal Gas Law

The ideal gas law can be written as

where

The alternate form ![]() comes from the statistical

mechanics derivation in which

comes from the statistical

mechanics derivation in which ![]() is the number of gas molecules in

the volume, and

is the number of gas molecules in

the volume, and ![]() is Boltzmann's constant. In this

formulation (the kinetic theory of ideal gases), the

average kinetic

energy of the gas molecules is given by

is Boltzmann's constant. In this

formulation (the kinetic theory of ideal gases), the

average kinetic

energy of the gas molecules is given by ![]() . Thus,

temperature is proportional to average kinetic energy of the

gas molecules, where the kinetic energy of a molecule

. Thus,

temperature is proportional to average kinetic energy of the

gas molecules, where the kinetic energy of a molecule ![]() with

translational speed

with

translational speed ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() .

.

In an ideal gas, the molecules are like little rubber balls (or rubbery assemblies of rubber balls) in a weightless vacuum, colliding with each other and the walls elastically and losslessly (an ``ideal rubber''). Electromagnetic forces among the molecules are neglected, other than the electron-orbital repulsion producing the elastic collisions; in other words, the molecules are treated as electrically neutral far away. (Gases of ionized molecules are called plasmas.)

The mass ![]() of the gas in volume

of the gas in volume ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() , where

, where ![]() is

the molar mass of the gass (about 29 g per mole for air). The

air density is thus

is

the molar mass of the gass (about 29 g per mole for air). The

air density is thus ![]() so that we can write

so that we can write

We normally do not need to consider the (nonlinear) ideal gas law in

audio acoustics because it is usually linearized about some

ambient pressure ![]() . The physical pressure is then

. The physical pressure is then ![]() , where

, where

![]() is the usual acoustic pressure-wave variable. That is, we are

only concerned with small pressure perturbations

is the usual acoustic pressure-wave variable. That is, we are

only concerned with small pressure perturbations ![]() in typical

audio acoustics situations, so that, for example, variations in volume

in typical

audio acoustics situations, so that, for example, variations in volume

![]() and density

and density ![]() can be neglected. Notable exceptions include

brass instruments which can achieve nonlinear sound-pressure regions,

especially near the mouthpiece [198,52].

Additionally, the aeroacoustics of air jets is nonlinear

[196,530,531,532,102,101].

can be neglected. Notable exceptions include

brass instruments which can achieve nonlinear sound-pressure regions,

especially near the mouthpiece [198,52].

Additionally, the aeroacoustics of air jets is nonlinear

[196,530,531,532,102,101].

Isothermal versus Isentropic

If air compression/expansion were isothermal (constant

temperature ![]() ), then, according to the ideal gas law

), then, according to the ideal gas law ![]() , the

pressure

, the

pressure ![]() would simply be proportional to density

would simply be proportional to density ![]() . It turns

out, however, that heat diffusion is much slower than audio acoustic

vibrations. As a result, air compression/expansion is much closer to

isentropic (constant entropy

. It turns

out, however, that heat diffusion is much slower than audio acoustic

vibrations. As a result, air compression/expansion is much closer to

isentropic (constant entropy ![]() ) in normal acoustic

situations. (An isentropic process is also called a reversible

adiabatic process.) This means that when air is compressed by

shrinking its volume

) in normal acoustic

situations. (An isentropic process is also called a reversible

adiabatic process.) This means that when air is compressed by

shrinking its volume ![]() , for example, not only does the pressure

, for example, not only does the pressure ![]() increase (§B.7.3), but the temperature

increase (§B.7.3), but the temperature ![]() increases as

well (as quantified in the next section). In a constant-entropy

compression/expansion, temperature changes are not given time to

diffuse away to thermal equilibrium. Instead, they remain largely

frozen in place. Compressing air heats it up, and relaxing the

compression cools it back down.

increases as

well (as quantified in the next section). In a constant-entropy

compression/expansion, temperature changes are not given time to

diffuse away to thermal equilibrium. Instead, they remain largely

frozen in place. Compressing air heats it up, and relaxing the

compression cools it back down.

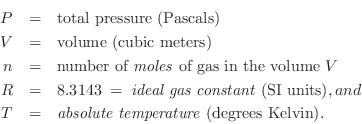

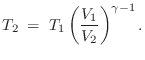

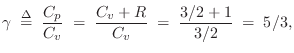

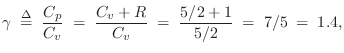

Adiabatic Gas Constant

The relative amount of compression/expansion energy that goes into

temperature ![]() versus pressure

versus pressure ![]() can be characterized by the heat capacity ratio

can be characterized by the heat capacity ratio

In terms of ![]() , we have

, we have

where

The value

![]() is typical for any diatomic

gas.B.31 Monatomic inert gases, on the other hand,

such as Helium, Neon, and Argon, have

is typical for any diatomic

gas.B.31 Monatomic inert gases, on the other hand,

such as Helium, Neon, and Argon, have

![]() . Carbon

dioxide, which is triatomic, has a heat capacity ratio

. Carbon

dioxide, which is triatomic, has a heat capacity ratio

![]() . We see that more complex molecules have lower

. We see that more complex molecules have lower ![]() values because they can store heat in more degrees of freedom.

values because they can store heat in more degrees of freedom.

Heat Capacity of Ideal Gases

In statistical thermodynamics [175,138],

it is derived that each molecular degree of freedom contributes ![]() to the molar heat capacity of an ideal gas, where again

to the molar heat capacity of an ideal gas, where again ![]() is the

ideal gas constant.

is the

ideal gas constant.

An ideal monatomic gas molecule (negligible spin) has only

three degrees of freedom: its kinetic energy in the three spatial

dimensions. Therefore,

![]() . This means we expect

. This means we expect

For an ideal diatomic gas molecule such as air, which can be pictured as a ``bar bell'' configuration of two rubber balls, two additional degrees of freedom are added, both associated with spinning the molecule about an axis orthogonal to the line connecting the atoms, and piercing its center of mass. There are two such axes. Spinning about the connecting axis is neglected because the moment of inertia is so much smaller in that case. Thus, for diatomic gases such as dry air, we expect

Speed of Sound in Air

The speed of sound in a gas depends primarily on the temperature, and can be estimated using the following formula from the kinetic theory of gases:B.33

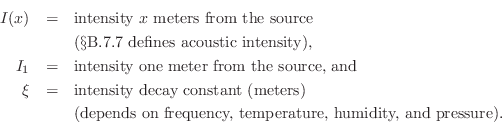

Air Absorption

This section provides some further details regarding acoustic air

absorption [318]. For a plane wave, the decline of

acoustic intensity as a function of propagation distance ![]() is given

by

is given

by

Tables B.1 and B.2 (adapted from [314]) give some typical values for air.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There is also a (weaker) dependence of air absorption on temperature [183].

Theoretical models of energy loss in a gas are developed in Morse and

Ingard [318, pp. 270-285]. Energy loss is caused by

viscosity, thermal diffusion, rotational

relaxation, vibration relaxation, and boundary losses

(losses due to heat conduction and viscosity at a wall or other

acoustic boundary). Boundary losses normally dominate by several

orders of magnitude, but in resonant modes, which have nodes along the

boundaries, interior losses dominate, especially for polyatomic gases

such as air.B.34 For air having moderate amounts of water

vapor (![]() ) and/or carbon dioxide (

) and/or carbon dioxide (![]() ), the loss and dispersion

due to

), the loss and dispersion

due to ![]() and

and ![]() vibration relaxation hysteresis becomes the

largest factor [318, p. 300]. The vibration here

is that of the molecule itself, accumulated over the course of many

collisions with other molecules. In this context, a diatomic molecule

may be modeled as two masses connected by an ideal spring. Energy

stored in molecular vibration typically dominates over that stored in

molecular rotation, for polyatomic gas molecules [318, p.

300]. Thus, vibration relaxation hysteresis is a loss

mechanism that converts wave energy into heat.

vibration relaxation hysteresis becomes the

largest factor [318, p. 300]. The vibration here

is that of the molecule itself, accumulated over the course of many

collisions with other molecules. In this context, a diatomic molecule

may be modeled as two masses connected by an ideal spring. Energy

stored in molecular vibration typically dominates over that stored in

molecular rotation, for polyatomic gas molecules [318, p.

300]. Thus, vibration relaxation hysteresis is a loss

mechanism that converts wave energy into heat.

In a resonant mode, the attenuation per wavelength due to vibration

relaxation is greatest when the sinusoidal period (of the resonance)

is equal to ![]() times the time-constant for vibration-relaxation.

The relaxation time-constant for oxygen is on the order of one

millisecond. The presence of water vapor (or other impurities)

decreases the vibration relaxation time, yielding loss maxima at

frequencies above 1000 rad/sec. The energy loss approaches zero as

the frequency goes to infinity (wavelength to zero).

times the time-constant for vibration-relaxation.

The relaxation time-constant for oxygen is on the order of one

millisecond. The presence of water vapor (or other impurities)

decreases the vibration relaxation time, yielding loss maxima at

frequencies above 1000 rad/sec. The energy loss approaches zero as

the frequency goes to infinity (wavelength to zero).

Under these conditions, the speed of sound is approximately that of dry air below the maximum-loss frequency, and somewhat higher above. Thus, the humidity level changes the dispersion cross-over frequency of the air in a resonant mode.

Next Section:

Wave Equation in Higher Dimensions

Previous Section:

Wave Equation for the Vibrating String