One-Port Network Theory

The basic idea of a one-port network [524] is shown in Fig. 7.5. The one-port is a ``black box'' with a single pair of input/output terminals, referred to as a port. A force is applied at the terminals and a velocity ``flows'' in the direction shown. The admittance ``seen'' at the port is called the driving point admittance. Network theory is normally described in terms of circuit theory elements, in which case a voltage is applied at the terminals and a current flows as shown. However, in our context, mechanical elements are preferable.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/loneport}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img1604.png) |

Series Combination of One-Ports

Figure 7.6 shows the series combination of two one-ports.

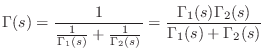

Impedances add in series, so the aggregate impedance is

![]() , and the admittance is

, and the admittance is

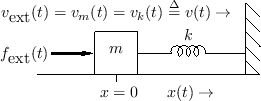

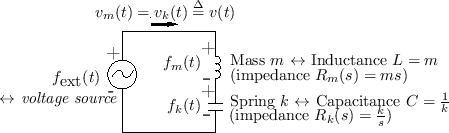

Mass-Spring-Wall System

In a physical situation, if two elements are connected in such a way that they share a common velocity, then they are in series. An example is a mass connected to one end of a spring, where the other end is attached to a rigid support, and the force is applied to the mass, as shown in Fig. 7.7.

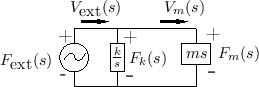

Figure 7.8 shows the electrical equivalent circuit corresponding to Fig.7.7.

|

|

Parallel Combination of One-Ports

Figure Fig.7.10 shows the parallel combination of two one-ports.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/lparallel}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img1611.png) |

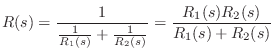

Admittances add in parallel, so the combined admittance is

![]() , and the impedance is

, and the impedance is

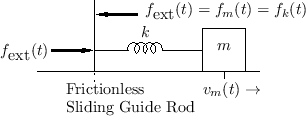

Spring-Mass System

When two physical elements are driven by a common force (yet

have independent velocities, as we'll soon see is quite possible),

they are formally in parallel. An example is a mass connected

to a spring in which the driving force is applied to one end of the

spring, and the mass is attached to the other end, as shown in

Fig.7.11. The compression force on the spring

is equal at all times to the rightward force on the mass. However,

the spring compression velocity ![]() does not always equal the

mass velocity

does not always equal the

mass velocity ![]() . We do have that the sum of the mass velocity

and spring compression velocity gives the velocity of the driving point,

i.e.,

. We do have that the sum of the mass velocity

and spring compression velocity gives the velocity of the driving point,

i.e.,

![]() . Thus, in a parallel connection, forces

are equal and velocities sum.

. Thus, in a parallel connection, forces

are equal and velocities sum.

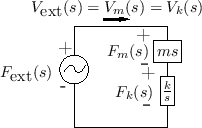

Figure 7.12 shows the electrical equivalent circuit corresponding to Fig.7.11.

|

Mechanical Impedance Analysis

Impedance analysis is commonly used to analyze electrical circuits [110]. By means of equivalent circuits, we can use the same analysis methods for mechanical systems.

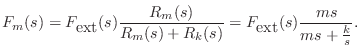

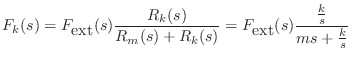

For example, referring to Fig.7.9, the Laplace transform of

the force on the spring ![]() is given by the so-called voltage

divider relation:8.2

is given by the so-called voltage

divider relation:8.2

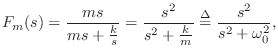

As a simple application, let's find the motion of the mass ![]() , after

time zero, given that the input force is an impulse at time 0:

, after

time zero, given that the input force is an impulse at time 0:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

V_m(s) &=& \frac{F_m(s)}{ms} \;=\; \frac{1}{m} \cdot \frac{s}{...

...}\right]\\ [5pt]

&\leftrightarrow& \frac{1}{m} \cos(\omega_0 t).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img1626.png)

Thus, the impulse response of the mass oscillates sinusoidally with

radian frequency

![]() , and amplitude

, and amplitude ![]() . The

velocity starts out maximum at time

. The

velocity starts out maximum at time ![]() , which makes physical sense.

Also, the momentum transferred to the mass at time 0 is

, which makes physical sense.

Also, the momentum transferred to the mass at time 0 is

![]() ;

this is also expected physically because the time-integral of the applied

force is 1 (the area under any impulse

;

this is also expected physically because the time-integral of the applied

force is 1 (the area under any impulse ![]() is 1).

is 1).

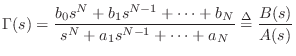

General One-Ports

An arbitrary interconnection of ![]() impedances and admittances, with input

and output force and/or velocities defined, results in a one-port with

admittance expressible as

impedances and admittances, with input

and output force and/or velocities defined, results in a one-port with

admittance expressible as

Passive One-Ports

It is well known that the impedance of every passive one-port is positive real (see §C.11.2). The reciprocal of a positive real function is positive real, so every passive impedance corresponds also to a passive admittance.

A complex-valued function of a complex variable ![]() is said to be

positive real (PR) if

is said to be

positive real (PR) if

- 1)

is real whenever

is real whenever  is real

is real

- 2)

-

whenever

whenever

.

.

A particularly important property of positive real

functions is that the phase is bounded between plus and minus ![]() degrees, i.e.,

degrees, i.e.,

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/interlace}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img1637.png) |

Referring to Fig.7.14, consider the graphical method for

computing phase response of a reactance from the pole zero diagram

[449].8.4Each zero on the positive ![]() axis contributes a net 90 degrees

of phase at frequencies above the zero. As frequency crosses the zero

going up, there is a switch from

axis contributes a net 90 degrees

of phase at frequencies above the zero. As frequency crosses the zero

going up, there is a switch from ![]() to

to ![]() degrees. For each

pole, the phase contribution switches from

degrees. For each

pole, the phase contribution switches from ![]() to

to ![]() degrees as

it is passed going up in frequency. In order to keep phase in

degrees as

it is passed going up in frequency. In order to keep phase in

![]() , it is clear that the poles and zeros must strictly

alternate. Moreover, all poles and zeros must be simple, since a

multiple poles or zero would swing the phase by more than

, it is clear that the poles and zeros must strictly

alternate. Moreover, all poles and zeros must be simple, since a

multiple poles or zero would swing the phase by more than ![]() degrees, and the reactance could not be positive real.

degrees, and the reactance could not be positive real.

The positive real property is fundamental to passive immittances and comes up often in the study of measured resonant systems. A practical modeling example (passive digital modeling of a guitar bridge) is discussed in §9.2.1.

Next Section:

Digitization of Lumped Models

Previous Section:

Impedance

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/lseries}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img1605.png)