High-Accuracy Piano-String Modeling

In [265,266], an extension of the mass-spring model of [391] was presented for the purpose of high-accuracy modeling of nonlinear piano strings struck by a hammer model such as described in §9.3.2. This section provides a brief overview.

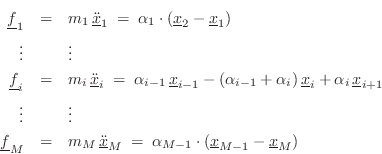

Figure 9.25 shows a mass-spring model in 3D space. From Hooke's Law (§B.1.3), we have

![\begin{eqnarray*}

m_1\, \underline{{\ddot x}}_1 \eqsp \underline{f}_1

&=& k\cdo...

...,\right\Vert}\right]\left(\underline{x}_2-\underline{x}_1\right)

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2276.png)

and similarly for mass 2, where

![]() is the vector

position of mass

is the vector

position of mass ![]() in 3D space.

in 3D space.

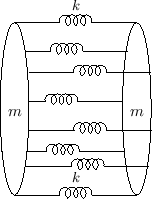

Generalizing to a chain of masses and spring is shown in Fig.9.26. Mass-spring chains--also called beaded strings--have been analyzed in numerous textbooks (e.g., [295,318]), and numerical software simulation is described in [391].

The force on the ![]() th mass can be expressed as

th mass can be expressed as

where

![$\displaystyle \alpha_i \isdefs k\cdot \left[1-\frac{l_0}{\left\Vert\,\underline{x}_{i+1}-\underline{x}_i\,\right\Vert}\right].

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2282.png)

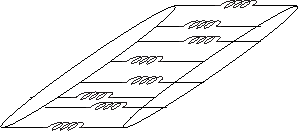

A Stiff Mass-Spring String Model

Following the classical derivation of the stiff-string wave equation [317,144], an obvious way to introduce stiffness in the mass-spring chain is to use a bundle of mass-spring chains to form a kind of ``lumped stranded cable''. One section of such a model is shown in Fig.9.27. Each mass is now modeled as a 2D mass disk. Complicated rotational dynamics can be avoided by assuming no torsional waves (no ``twisting'' motion) (§B.4.20).

A three-spring-per-mass model is shown in Fig.9.28

[266]. The spring positions alternate between angles

![]() , say, on one side of a mass disk and

, say, on one side of a mass disk and

![]() on the other side in order to provide effectively

six spring-connection points around the mass disk for only

three connecting springs per section. This improves isotropy

of the string model with respect to bending direction.

on the other side in order to provide effectively

six spring-connection points around the mass disk for only

three connecting springs per section. This improves isotropy

of the string model with respect to bending direction.

A problem with the simple mass-spring-chain-bundle is that there is no

resistance whatsoever to shear deformation, as is clear from

Fig.9.29. To rectify this problem (which does not

arise due implicit assumptions when classically deriving the

stiff-string wave equation), diagonal springs can be added to the

model, as shown in

Fig.![]() .

.

In the simulation results reported in [266], the spring-constants of the shear springs were chosen so that their stiffness in the longitudinal direction would equal that of the longitudinal springs.

Nonlinear Piano-String Equations of Motion in State-Space Form

For the flexible (non-stiff) mass-spring string, referring to

Fig.9.26 and Eq.![]() (9.34), we have the following

equations of motion:

(9.34), we have the following

equations of motion:

or, in ![]() vector form,

vector form,

Finite Difference Implementation

Digitizing

![]() via the centered second-order difference

[Eq.

via the centered second-order difference

[Eq.![]() (7.5)]

(7.5)]

Note that requiring three adjacent spatial string samples to be in

contact with the piano hammer during the attack (which helps to

suppress aliasing of spatial frequencies on the string during the

attack) implies a sampling rate in the vicinity of 6 megahertz

[265]. Thus, the model is expensive to compute!

However, results to date show a high degree of accuracy, as desired.

In particular, the stretching of the partial overtones in the

stiff-string model of

Fig.![]() has

been measured to be highly accurate despite using only three spring

attachment points on one side of each mass disk [265].

has

been measured to be highly accurate despite using only three spring

attachment points on one side of each mass disk [265].

See [53] for alternative finite-difference formulations that better preserve physical energy and have other nice properties worth considering.

Next Section:

Commuted Piano Synthesis

Previous Section:

Nonlinear Piano Strings

![\includegraphics[width=0.35\twidth]{eps/massspringmass}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2271.png)

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\twidth]{eps/massspringstring}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2278.png)

![\includegraphics[width=0.8\twidth]{eps/masssprings3circ}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2286.png)

![\includegraphics[width=0.4\twidth]{eps/masssprings3shear}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2288.png)