Window Method for FIR Filter Design

The window method for digital filter design is fast, convenient, and robust, but generally suboptimal. It is easily understood in terms of the convolution theorem for Fourier transforms, making it instructive to study after the Fourier theorems and windows for spectrum analysis. It can be effectively combined with the frequency sampling method, as we will see in §4.6 below.

The window method consists of simply ``windowing'' a theoretically

ideal filter impulse response ![]() by some suitably chosen window

function

by some suitably chosen window

function ![]() , yielding

, yielding

| (5.8) |

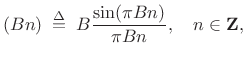

For example, as derived in Eq.

|

(5.9) |

where

Since

![]() sinc

sinc![]() decays away from time 0 as

decays away from time 0 as ![]() , we would

expect to be able to truncate it to the interval

, we would

expect to be able to truncate it to the interval ![]() , for some

sufficiently large

, for some

sufficiently large ![]() , and obtain a pretty good FIR filter which

approximates the ideal filter. This would be an example of using the

window method with the rectangular window. We saw in

§4.3 that such a choice is optimal in the least-squares

sense, but it designs relatively poor audio filters. Choosing other

windows corresponds to tapering the ideal impulse response to

zero instead of truncating it. Tapering better preserves the shape of

the desired frequency response, as we will see. By choosing the

window carefully, we can manage various trade-offs so as to maximize

the filter-design quality in a given application.

, and obtain a pretty good FIR filter which

approximates the ideal filter. This would be an example of using the

window method with the rectangular window. We saw in

§4.3 that such a choice is optimal in the least-squares

sense, but it designs relatively poor audio filters. Choosing other

windows corresponds to tapering the ideal impulse response to

zero instead of truncating it. Tapering better preserves the shape of

the desired frequency response, as we will see. By choosing the

window carefully, we can manage various trade-offs so as to maximize

the filter-design quality in a given application.

Window functions are always time limited. This means there is

always a finite integer ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all

![]() . The final windowed impulse response

. The final windowed impulse response

![]() is thus always time-limited, as needed for practical

implementation. The window method always designs a

finite-impulse-response (FIR) digital filter (as opposed to an

infinite-impulse-response (IIR) digital filter).

is thus always time-limited, as needed for practical

implementation. The window method always designs a

finite-impulse-response (FIR) digital filter (as opposed to an

infinite-impulse-response (IIR) digital filter).

By the dual of the convolution theorem, pointwise multiplication in

the time domain corresponds to convolution in the frequency domain.

Thus, the designed filter ![]() has a frequency response given by

has a frequency response given by

| (5.10) |

where

- The pass-band gain is primarily the area under the

main lobe of the window transform, provided the main lobe

``fits'' inside the pass-band (i.e., the total lowpass bandwidth

is greater than or equal to the main-lobe width

of

is greater than or equal to the main-lobe width

of  ).

).

- The stop-band gain is given by an integral over a portion

of the side lobes of the window transform. Since side-lobes

oscillate about zero, a finite integral over them is normally much

smaller than the side-lobes themselves, due to adjacent side-lobe

cancellation under the integral.

- The best stop-band performance occurs when the cut-off

frequency is set so that the stop-band side-lobe integral traverses a

whole number of side lobes.

- The transition bandwidth is equal to the bandwidth of

the main lobe of the window transform, again provided that the main

lobe ``fits'' inside the pass-band.

- For very small lowpass bandwidths

,

,  approaches an

impulse in the frequency domain. Since the impulse is the

identity operator under convolution, the resulting lowpass filter

approaches an

impulse in the frequency domain. Since the impulse is the

identity operator under convolution, the resulting lowpass filter

approaches the window transform

approaches the window transform  for small

for small

. In particular, the stop-band gain approaches the window

side-lobe level, and the transition width approaches half the

main-lobe width. Thus, for good results, the lowpass cut-off

frequency should be set no lower than half the window's main-lobe

width.

. In particular, the stop-band gain approaches the window

side-lobe level, and the transition width approaches half the

main-lobe width. Thus, for good results, the lowpass cut-off

frequency should be set no lower than half the window's main-lobe

width.

Matlab Support for the Window Method

Octave and the Matlab Signal Processing Toolbox have two functions implementing the window method for FIR digital filter design:

- fir1 designs lowpass, highpass, bandpass, and

multi-bandpass filters.

- fir2 takes an arbitrary magnitude frequency response

specification.

Bandpass Filter Design Example

The matlab code below designs a bandpass filter which passes

frequencies between 4 kHz and 6 kHz, allowing transition bands from 3-4

kHz and 6-8 kHz (i.e., the stop-bands are 0-3 kHz and 8-10 kHz, when the

sampling rate is 20 kHz). The desired stop-band attenuation is 80 dB,

and the pass-band ripple is required to be no greater than 0.1 dB. For

these specifications, the function kaiserord returns a beta

value of

![]() and a window length of

and a window length of ![]() . These values

are passed to the function kaiser which computes the window

function itself. The ideal bandpass-filter impulse response is

computed in fir1, and the supplied Kaiser window is applied

to shorten it to length

. These values

are passed to the function kaiser which computes the window

function itself. The ideal bandpass-filter impulse response is

computed in fir1, and the supplied Kaiser window is applied

to shorten it to length ![]() .

.

fs = 20000; % sampling rate F = [3000 4000 6000 8000]; % band limits A = [0 1 0]; % band type: 0='stop', 1='pass' dev = [0.0001 10^(0.1/20)-1 0.0001]; % ripple/attenuation spec [M,Wn,beta,typ] = kaiserord(F,A,dev,fs); % window parameters b = fir1(M,Wn,typ,kaiser(M+1,beta),'noscale'); % filter design

Note the conciseness of the matlab code thanks to the use of kaiserord and fir1 from Octave or the Matlab Signal Processing Toolbox.

Figure 4.6 shows the magnitude frequency response

![]() of the resulting FIR filter

of the resulting FIR filter ![]() . Note that

the upper pass-band edge has been moved to 6500 Hz instead of 6000 Hz,

and the stop-band begins at 7500 Hz instead of 8000 Hz as requested.

While this may look like a bug at first, it's actually a perfectly

fine solution. As discussed earlier (§4.5), all

transition-widths in filters designed by the window method must equal

the window-transform's main-lobe width. Therefore, the only way to

achieve specs when there are multiple transition regions specified is

to set the main-lobe width to the minimum transition width.

For the others, it makes sense to center the transition within

the requested transition region.

. Note that

the upper pass-band edge has been moved to 6500 Hz instead of 6000 Hz,

and the stop-band begins at 7500 Hz instead of 8000 Hz as requested.

While this may look like a bug at first, it's actually a perfectly

fine solution. As discussed earlier (§4.5), all

transition-widths in filters designed by the window method must equal

the window-transform's main-lobe width. Therefore, the only way to

achieve specs when there are multiple transition regions specified is

to set the main-lobe width to the minimum transition width.

For the others, it makes sense to center the transition within

the requested transition region.

Under the Hood of kaiserord

Without kaiserord, we would need to implement Kaiser's

formula [115,67] for estimating the Kaiser-window

![]() required to achieve the given filter specs:

required to achieve the given filter specs:

where

A similar function from [198] for window design (as opposed to filter design5.7) is

where now

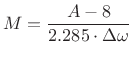

Similarly, the filter order ![]() is estimated from stop-band

attenuation

is estimated from stop-band

attenuation ![]() and desired transition width

and desired transition width

![]() using the

empirical formula

using the

empirical formula

|

(5.13) |

where

Without the function fir1, we would have to manually

implement the window method of filter design by (1) constructing the

impulse response of the ideal bandpass filter ![]() (a cosine

modulated sinc function), (2) computing the Kaiser window

(a cosine

modulated sinc function), (2) computing the Kaiser window ![]() using

the estimated length and

using

the estimated length and ![]() from above, then finally (3)

windowing the ideal impulse response with the Kaiser window to obtain

the FIR filter coefficients

from above, then finally (3)

windowing the ideal impulse response with the Kaiser window to obtain

the FIR filter coefficients

![]() . A manual design of

this nature will be illustrated in the Hilbert transform example of

§4.6.

. A manual design of

this nature will be illustrated in the Hilbert transform example of

§4.6.

Comparison to the Optimal Chebyshev FIR Bandpass Filter

To provide some perspective on the results, let's compare the window method to the optimal Chebyshev FIR filter (§4.10) for the same length and design specifications above.

The following Matlab code illustrates two different bandpass filter designs. The first (different transition bands) illustrates a problem we'll look at. The second (equal transition bands, commented out), avoids the problem.

M = 101; normF = [0 0.3 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0]; % transition bands different %normF = [0 0.3 0.4 0.6 0.7 1.0]; % transition bands the same amp = [0 0 1 1 0 0]; % desired amplitude in each band [b2,err2] = firpm(M-1,normF,amp); % optimal filter of length M

Figure 4.7 shows the frequency response of the Chebyshev FIR filter designed by firpm, to be compared with the window-method FIR filter in Fig.4.6. Note that the upper transition band ``blows up''. This is a well known failure mode in FIR filter design using the Remez exchange algorithm [176,224]. It can be eliminated by narrowing the transition band, as shown in Fig.4.8. There is no error penalty in the transition region, so it is necessary that each one be ``sufficiently narrow'' to avoid this phenomenon.

Remember the rule of thumb that the narrowest transition-band possible

for a length ![]() FIR filter is on the order of

FIR filter is on the order of ![]() , because

that's the width of the main-lobe of a length

, because

that's the width of the main-lobe of a length ![]() rectangular window

(measured between zero-crossings) (§3.1.2). Therefore, this

value is quite exact for the transition-widths of FIR bandpass filters

designed by the window method using the rectangular window (when the

main-lobe fits entirely within the adjacent pass-band and stop-band).

For a Hamming window, the window-method transition width would instead

be

rectangular window

(measured between zero-crossings) (§3.1.2). Therefore, this

value is quite exact for the transition-widths of FIR bandpass filters

designed by the window method using the rectangular window (when the

main-lobe fits entirely within the adjacent pass-band and stop-band).

For a Hamming window, the window-method transition width would instead

be ![]() . Thus, we might expect an optimal Chebyshev design to

provide transition widths in the vicinity of

. Thus, we might expect an optimal Chebyshev design to

provide transition widths in the vicinity of ![]() , but probably

not too close to

, but probably

not too close to ![]() or below

In the example above, where the sampling rate was

or below

In the example above, where the sampling rate was ![]() kHz, and the

filter length was

kHz, and the

filter length was ![]() , we expect to be able to achieve transition

bands circa

, we expect to be able to achieve transition

bands circa

![]() Hz, but not so low

as

Hz, but not so low

as

![]() Hz. As we found above,

Hz. As we found above,

![]() Hz was under-constrained, while

Hz was under-constrained, while ![]() Hz was ok, being near

the ``Hamming transition width.''

Hz was ok, being near

the ``Hamming transition width.''

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fltDesignRemez}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img738.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fltDesignRemezTighter}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img739.png) |

Next Section:

Hilbert Transform Design Example

Previous Section:

Frequency Sampling Method for FIR Filter Design

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fltDesign}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img724.png)

![$\displaystyle \beta = \left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0.1102(A-8.7), & A > 50 \\ [5pt] 0.5842(A-21)^{0.4} + 0.07886(A-21), & 21< A < 50 \\ [5pt] 0, & A < 21, \\ \end{array} \right. \protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img725.png)

![$\displaystyle \beta = \left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & A<13.26 \\ [5pt] 0.76609(A-13.26)^{0.4} + 0.09834(A-13.26), & 13.26< A < 60 \\ [5pt] 0.12438*(A+6.3), & 60<A<120, \\ \end{array} \right. \protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img728.png)