Phase Vocoder Sinusoidal Modeling

As mentioned in §G.7, the phase vocoder had become a standard analysis tool for additive synthesis (§G.8) by the late 1970s [186,187]. This section summarizes that usage.

In analysis for additive synthesis, we convert a time-domain signal

![]() into a collection of amplitude envelopes

into a collection of amplitude envelopes ![]() and frequency envelopes

and frequency envelopes

![]() (or phase modulation envelopes

(or phase modulation envelopes

![]() ), as graphed in Fig.G.12.

It is usually desired that these envelopes be slowly varying

relative to the original signal. This leads to the assumption that we

have at most one sinusoid in each filter-bank channel. (By

``sinusoid'' we mean, of course, ``quasi sinusoid,'' since its

amplitude and phase may be slowly time-varying.) The channel-filter

frequency response is given by the FFT of the analysis window used

(Chapter 9).

), as graphed in Fig.G.12.

It is usually desired that these envelopes be slowly varying

relative to the original signal. This leads to the assumption that we

have at most one sinusoid in each filter-bank channel. (By

``sinusoid'' we mean, of course, ``quasi sinusoid,'' since its

amplitude and phase may be slowly time-varying.) The channel-filter

frequency response is given by the FFT of the analysis window used

(Chapter 9).

The signal in the ![]() subband (filter-bank channel) can be

written

subband (filter-bank channel) can be

written

In this expression,

Typically, the instantaneous phase modulation ![]() is

differentiated to obtain instantaneous frequency deviation:

is

differentiated to obtain instantaneous frequency deviation:

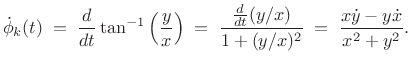

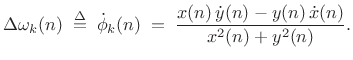

|

(G.4) |

The analysis and synthesis signal models are summarized in Fig.G.9.

Computing Vocoder Parameters

To compute the amplitude ![]() at the output of the

at the output of the ![]() th subband,

we can apply an envelope follower. Classically, such as in the

original vocoder, this can be done by full-wave rectification and

subsequent low pass filtering, as shown in Fig.G.10. This

produces an approximation of the average power in each subband.

th subband,

we can apply an envelope follower. Classically, such as in the

original vocoder, this can be done by full-wave rectification and

subsequent low pass filtering, as shown in Fig.G.10. This

produces an approximation of the average power in each subband.

In digital signal processing, we can do much better than the classical amplitude-envelope follower: We can measure instead the instantaneous amplitude of the (assumed quasi sinusoidal) signal in each filter band using so-called analytic signal processing (introduced in §4.6). For this, we generalize (G.3) to the real-part of the corresponding analytic signal:

In general, when both amplitude and phase are needed, we must compute two real signals for each vocoder channel:

We call

In order to determine these signals, we need to compute the analytic

signal ![]() from its real part

from its real part ![]() . Ideally, the imaginary

part of the analytic signal is obtained from its real part using

the Hilbert transform (§4.6), as shown

in Fig.G.11.

. Ideally, the imaginary

part of the analytic signal is obtained from its real part using

the Hilbert transform (§4.6), as shown

in Fig.G.11.

Using the Hilbert-transform filter, we obtain the analytic signal in ``rectangular'' (Cartesian) form:

| (G.7) |

To obtain the instantaneous amplitude and phase, we simply convert each complex value of

| (G.8) |

as given by (G.6).

Frequency Envelopes

It is convenient in practice to work with instantaneous frequency deviation instead of phase:

|

(G.9) |

Since the

Note that ![]() is a narrow-band signal centered about the channel

frequency

is a narrow-band signal centered about the channel

frequency ![]() . As detailed in Chapter 9, it is typical

to heterodyne the channel signals to ``base band'' by shifting

the input spectrum by

. As detailed in Chapter 9, it is typical

to heterodyne the channel signals to ``base band'' by shifting

the input spectrum by ![]() so that the channel bandwidth is

centered about frequency zero (dc). This may be expressed by

modulating the analytic signal by

so that the channel bandwidth is

centered about frequency zero (dc). This may be expressed by

modulating the analytic signal by

![]() to get

to get

|

(G.10) |

The `b' superscript here stands for ``baseband,'' i.e., the channel-filter frequency-response is centered about dc. Working at baseband, we may compute the frequency deviation as simply the time-derivative of the instantaneous phase of the analytic signal:

|

(G.11) |

where

|

(G.12) |

denotes the time derivative of

|

(G.13) |

For discrete time, we replace

Initially, the sliding FFT was used (hop size

Using (G.6) and (G.14) to compute the instantaneous amplitude and frequency for each subband, we obtain data such as shown qualitatively in Fig.G.12. A matlab algorithm for phase unwrapping is given in §F.4.1.

Envelope Compression

Once we have our data in the form of amplitude and frequency envelopes

for each filter-bank channel, we can compress them by a large factor.

If there are ![]() channels, we nominally expect to be able to

downsample by a factor of

channels, we nominally expect to be able to

downsample by a factor of ![]() , as discussed initially in Chapter 9

and more extensively in Chapter 11.

, as discussed initially in Chapter 9

and more extensively in Chapter 11.

In early computer music [97,186], amplitude and frequency envelopes were ``downsampled'' by means of piecewise linear approximation. That is, a set of breakpoints were defined in time between which linear segments were used. These breakpoints correspond to ``knot points'' in the context of polynomial spline interpolation [286]. Piecewise linear approximation yielded large compression ratios for relatively steady tonal signals.G.10For example, compression ratios of 100:1 were not uncommon for isolated ``toots'' on tonal orchestral instruments [97].

A more straightforward method is to simply downsample each envelope by

some factor. Since each subband is bandlimited to the channel

bandwidth, we expect a downsampling factor on the order of the number

of channels in the filter bank. Using a hop size ![]() in the STFT

results in downsampling by the factor

in the STFT

results in downsampling by the factor ![]() (as discussed

in §9.8). If

(as discussed

in §9.8). If ![]() channels are downsampled by

channels are downsampled by ![]() , then the

total number of samples coming out of the filter bank equals the

number of samples going into the filter bank. This may be called

critical downsampling, which is invariably used in filter banks

for audio compression, as discussed further in Chapter 11. A benefit

of converting a signal to critically sampled filter-bank form is that

bits can be allocated based on the amount of energy in each subband

relative to the psychoacoustic masking threshold in that band.

Bit-allocation is typically different for tonal and noise signals in a

band [113,25,16].

, then the

total number of samples coming out of the filter bank equals the

number of samples going into the filter bank. This may be called

critical downsampling, which is invariably used in filter banks

for audio compression, as discussed further in Chapter 11. A benefit

of converting a signal to critically sampled filter-bank form is that

bits can be allocated based on the amount of energy in each subband

relative to the psychoacoustic masking threshold in that band.

Bit-allocation is typically different for tonal and noise signals in a

band [113,25,16].

Vocoder-Based Additive-Synthesis Limitations

Using the phase-vocoder to compute amplitude and frequency envelopes for additive synthesis works best for quasi-periodic signals. For inharmonic signals, the vocoder analysis method can be unwieldy: The restriction of one sinusoid per subband leads to many ``empty'' bands (since radix-2 FFT filter banks are always uniformly spaced). As a result, we have to compute many more filter bands than are actually needed, and the empty bands need to be ``pruned'' in some way (e.g., based on an energy detector within each band). The unwieldiness of a uniform filter bank for tracking inharmonic partial overtones through time led to the development of sinusoidal modeling based on the STFT, as described in §G.11.2 below.

Another limitation of the phase-vocoder analysis was that it did not capture the attack transient very well in the amplitude and frequency envelopes computed. This is because an attack transient typically only partially filled an STFT analysis window. Moreover, filter-bank amplitude and frequency envelopes provide an inefficient model for signals that are noise-like, such as a flute with a breathy attack. These limitations are addressed by sinusoidal modeling, sines+noise modeling, and sines+noise+transients modeling, as discussed starting in §10.4 below (as well as in §10.4).

The phase vocoder was not typically implemented as an identity system due mainly to the large data reduction of the envelopes (piecewise linear approximation). However, it could be used as an identity system by keeping the envelopes at the full signal sampling rate and retaining the initial phase information for each channel. Instantaneous phase is then reconstructed as the initial phase plus the time-integral of the instantaneous frequency (given by the frequency envelope).

Further Reading on Vocoders

This section has focused on use of the phase vocoder as an analysis filter-bank for additive synthesis, following in the spirit of Homer Dudley's analog channel vocoder (§G.7), but taken to the digital domain. For more about vocoders and phase-vocoders in computer music, see, e.g., [19,183,215,235,187,62].

Next Section:

Spectral Modeling Synthesis

Previous Section:

Frequency Modulation (FM) Synthesis

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/pvchan}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img3000.png)

![\begin{psfrags}

% latex2html id marker 42527\psfrag{x} []{ \LARGE$ x_k(t)$\ }\psfrag{xkt} []{ \LARGE$ \tilde{x}_k(t)$\ }\psfrag{xk} []{ \LARGE$ x_k(t)$\ }\psfrag{output} []{ \LARGE$ y_k=h*\tilde{x}_k $\ }\begin{figure}[htbp]

\includegraphics[width=\textwidth ]{eps/envelope}

\caption{Classic method for amplitude envelope

extraction in continuous-time analog circuits.}

\end{figure}

\end{psfrags}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img3001.png)

![$\displaystyle \tan^{-1} \left[ \frac{\mbox{im\ensuremath{\left\{x_k^a(t)\right\}}}}

{\mbox{re\ensuremath{\left\{x_k^a(t)\right\}}}} \right] - \omega_kt

\protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img3011.png)

![\begin{psfrags}

% latex2html id marker 42563\psfrag{x} []{ \LARGE$ x_k(t)$\ }\psfrag{Rex} []{ \LARGE$ \mbox{re\ensuremath{\left\{x_k^a(t)\right\}}}$\ }\psfrag{Imx} []{ \LARGE$ \mbox{im\ensuremath{\left\{x_k^a(t)\right\}}}$\ }\begin{figure}[htbp]

\includegraphics[width=0.8\twidth]{eps/hilbert}

\caption{Creating an analytic signal

from its real part using the Hilbert transform

(\textit{cf.}{} \sref {hilbert}).}

\end{figure}

\end{psfrags}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img3015.png)

![\begin{psfrags}

% latex2html id marker 42622\psfrag{ak} []{ \LARGE$ a_k(t)$\ }\psfrag{wkt} []{ \LARGE$ \Delta\omega_k(t)=\dot{\phi_k}(t) $\ }\psfrag{wk} []{ \LARGE$ 0 $\ }\psfrag{t} []{ \LARGE$ t$\ }\begin{figure}[htbp]

\includegraphics[width=3.5in]{eps/traj}

\caption{Example amplitude envelope (top)

and frequency envelope (bottom).}

\end{figure}

\end{psfrags}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img3033.png)