Multirate Filter Banks

The preceding chapters have been concerned essentially with the short-time Fourier transform and all that goes with it. After developing the overlap-add point of view in Chapter 8, we developed the alternative (dual) filter-bank point of view in Chapter 9. This chapter is concerned more broadly with filter banks, whether they are implemented using an FFT or by some other means. In the end, however, we will come full circle and look at the properly configured STFT as an example of a perfect reconstruction (PR) filter bank as defined herein. Moreover, filter banks in practice are normally implemented using FFT methods.

The subject of PR filter banks is normally considered only in the context of systems for audio compression, and they are normally critically sampled in both time and frequency. This book, on the other hand, belongs to a tiny minority which is not concerned with compression at all, but rather useful time-frequency decompositions for sound, and corresponding applications in music and digital audio effects.

Perhaps the most important new topic introduced in this chapter is the polyphase representation for filter banks. This is both an important analysis tool and a basis for efficient implementation. We will see that it can be seen as a generalization of the overlap-add approach discussed in Chapter 8.

The polyphase representation will make it straightforward to determine general conditions for perfect reconstruction in any filter bank. The STFT will provide some special cases, but there will be many more. In particular, the filter banks used in perceptual audio coding will be special cases as well. Polyphase analysis is used to derive classes of PR filter banks called ``paraunitary,'' ``cosine modulated,'' and ``pseudo-quadrature mirror'' filter banks, among others.

Another extension we will take up in this chapter is multirate systems. Multirate filter banks use different sampling rates in different channels, matched to different filter bandwidths. Multirate filter banks are very important in audio work because the filtering by the inner ear is similarly a variable resolution ``filter bank'' using wider pass-bands at higher frequencies. Finally, the related subject of wavelet filter banks is briefly introduced, and further reading is recommended.

Upsampling and Downsampling

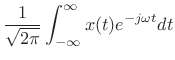

For the DTFT, we proved in Chapter 2 (p.

p. ![]() ) the stretch theorem (repeat theorem) which

relates upsampling (``stretch'') to spectral copies (``images'') in

the DTFT context; this is the discrete-time counterpart of the scaling

theorem for continuous-time Fourier transforms

(§B.4). Also, §2.3.12 discusses the downsampling

theorem (aliasing theorem) for DTFTs which relates downsampling to

aliasing for discrete-time signals. In this section, we review the

main results.

) the stretch theorem (repeat theorem) which

relates upsampling (``stretch'') to spectral copies (``images'') in

the DTFT context; this is the discrete-time counterpart of the scaling

theorem for continuous-time Fourier transforms

(§B.4). Also, §2.3.12 discusses the downsampling

theorem (aliasing theorem) for DTFTs which relates downsampling to

aliasing for discrete-time signals. In this section, we review the

main results.

Upsampling (Stretch) Operator

Figure 11.1 shows the graphical symbol for a digital upsampler

by the factor ![]() . To upsample by the integer factor

. To upsample by the integer factor ![]() , we simply

insert

, we simply

insert ![]() zeros between

zeros between ![]() and

and ![]() for all

for all ![]() . In other

words, the upsampler implements the stretch operator defined

in §2.3.9:

. In other

words, the upsampler implements the stretch operator defined

in §2.3.9:

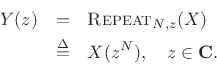

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(n) &=& \hbox{\sc Stretch}_{N,n}(x)\\

&\isdef & \left\{\begin{array}{ll}

x(n/N), & \frac{n}{N}\in{\bf Z} \\ [5pt]

0, & \hbox{otherwise}. \\

\end{array} \right.

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1924.png)

In the frequency domain, we have, by the stretch (repeat) theorem for DTFTs:

Plugging in

![]() , we see that the spectrum on

, we see that the spectrum on

![]() contracts by the factor

contracts by the factor ![]() , and

, and ![]() images appear around the

unit circle. For

images appear around the

unit circle. For ![]() , this is depicted in Fig.11.2.

, this is depicted in Fig.11.2.

Downsampling (Decimation) Operator

Figure 11.3 shows the symbol for downsampling by the factor ![]() .

The downsampler selects every

.

The downsampler selects every ![]() th sample and discards the rest:

th sample and discards the rest:

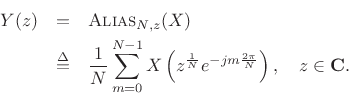

In the frequency domain, we have

Thus, the frequency axis is expanded by the factor ![]() , wrapping

, wrapping

![]() times around the unit circle, adding to itself

times around the unit circle, adding to itself ![]() times. For

times. For

![]() , two partial spectra are summed, as indicated in Fig.11.4.

, two partial spectra are summed, as indicated in Fig.11.4.

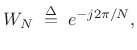

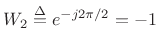

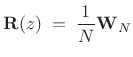

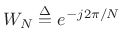

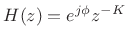

Using the common twiddle factor notation

|

(12.1) |

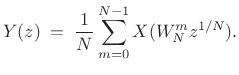

the aliasing expression can be written as

Example: Downsampling by 2

For ![]() , downsampling by 2 can be expressed as

, downsampling by 2 can be expressed as

![]() , so that

(since

, so that

(since

)

)

![\begin{eqnarray*}

Y(z) &=& \frac{1}{2}\left[X\left(W^0_2 z^{1/2}\right) + X\left(W^1_2 z^{1/2}\right)\right] \\ [5pt]

&=& \frac{1}{2}\left[X\left(e^{-j2\pi 0/2} z^{1/2}\right) + X\left(e^{-j2\pi 1/2}z^{1/2}\right)\right] \\ [5pt]

&=& \frac{1}{2}\left[X\left(z^{1/2}\right) + X\left(-z^{1/2}\right)\right] \\ [5pt]

&=& \frac{1}{2}\left[\hbox{\sc Stretch}_2(X) + \hbox{\sc Stretch}_2\left(\hbox{\sc Shift}_\pi(X)\right)\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1936.png)

Example: Upsampling by 2

For ![]() , upsampling (stretching) by 2 can be expressed as

, upsampling (stretching) by 2 can be expressed as

![]() , so that

, so that

| (12.2) |

as discussed more fully in §2.3.11.

Filtering and Downsampling

Because downsampling by ![]() causes aliasing of any frequencies in the

original signal above

causes aliasing of any frequencies in the

original signal above

![]() , the input signal may need to

be first lowpass-filtered to prevent this aliasing, as shown in

Fig.11.5.

, the input signal may need to

be first lowpass-filtered to prevent this aliasing, as shown in

Fig.11.5.

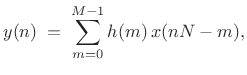

Suppose we implement such an anti-aliasing lowpass filter ![]() as an

FIR filter of length

as an

FIR filter of length ![]() with cut-off frequency

with cut-off frequency

![]() .12.1 This is drawn in direct form in

Fig.11.6.

.12.1 This is drawn in direct form in

Fig.11.6.

![\includegraphics[width=0.6\twidth]{eps/down_FIR}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1943.png) |

We do not need ![]() out of every

out of every ![]() filter output samples due to the

filter output samples due to the

![]() :

:![]() downsampler. To realize this savings, we can commute the

downsampler through the adders inside the FIR filter to obtain the

result shown in Fig.11.7. The multipliers are now running

at

downsampler. To realize this savings, we can commute the

downsampler through the adders inside the FIR filter to obtain the

result shown in Fig.11.7. The multipliers are now running

at ![]() times the sampling frequency of the input signal

times the sampling frequency of the input signal ![]() .

This reduces the computation requirements by a factor of

.

This reduces the computation requirements by a factor of ![]() . The

downsampler outputs in Fig.11.7 are called polyphase

signals. The overall system is a summed polyphase filter

bank in which each ``subphase filter'' is a constant scale factor

. The

downsampler outputs in Fig.11.7 are called polyphase

signals. The overall system is a summed polyphase filter

bank in which each ``subphase filter'' is a constant scale factor

![]() . As we will see, more general subphase filters can be used to

implement time-domain aliasing as needed for Portnoff windows

(§9.7).

. As we will see, more general subphase filters can be used to

implement time-domain aliasing as needed for Portnoff windows

(§9.7).

We may describe the polyphase processing in the anti-aliasing filter of Fig.11.7 as follows:

- Subphase signal 0

![$\displaystyle x(nN)\left\vert _{n=0}^{\infty}\right. \eqsp [x_0,x_N,x_{2N},\ldots]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1947.png)

(12.3)

is scaled by .

.

- Subphase signal 1

![$\displaystyle x(nN-1)\left\vert _{n=0}^{\infty}\right.\eqsp [x_{-1},x_{N-1},x_{2N-1},\ldots]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1948.png)

(12.4)

is scaled by ,

,

- Subphase signal

![$\displaystyle x(nN-m)\left\vert _{n=0}^{\infty}\right.\eqsp [x_{-m},x_{N-m},x_{2N-m},\ldots]

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1951.png)

is scaled by .

.

|

(12.5) |

which we recognize as a direct-form-convolution implementation of a length

The summed polyphase signals of Fig.11.7 can be interpreted

as ``serial to parallel conversion'' from an ``interleaved'' stream of

scalar samples ![]() to a ``deinterleaved'' sequence of buffers (each

length

to a ``deinterleaved'' sequence of buffers (each

length ![]() ) every

) every ![]() samples, followed by an inner product of each

buffer with

samples, followed by an inner product of each

buffer with

![]() . The same operation may be

visualized as a deinterleaving through variable gains into a running

sum, as shown in Fig.11.8.

. The same operation may be

visualized as a deinterleaving through variable gains into a running

sum, as shown in Fig.11.8.

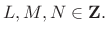

Polyphase Decomposition

The previous section derived an efficient polyphase implementation of

an FIR filter ![]() whose output was downsampled by the factor

whose output was downsampled by the factor ![]() . The

derivation was based on commuting the downsampler with the FIR

summer. We now derive the polyphase representation of a filter of any

length algebraically by splitting the impulse response

. The

derivation was based on commuting the downsampler with the FIR

summer. We now derive the polyphase representation of a filter of any

length algebraically by splitting the impulse response ![]() into

into

![]() polyphase components.

polyphase components.

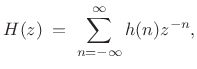

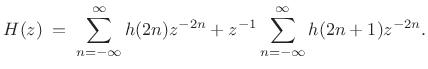

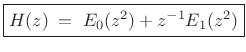

Two-Channel Case

The simplest nontrivial case is ![]() channels. Starting with a

general linear time-invariant filter

channels. Starting with a

general linear time-invariant filter

|

(12.6) |

we may separate the even- and odd-indexed terms to get

|

(12.7) |

We define the polyphase component filters as follows:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

E_0(z)&=&\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty}h(2n)z^{-n}\\ [5pt]

E_1(z)&=&\sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty}h(2n+1)z^{-n}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1958.png)

![]() and

and ![]() are the polyphase components

of the polyphase decomposition of

are the polyphase components

of the polyphase decomposition of ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

Now write ![]() in terms of its polyphase components:

in terms of its polyphase components:

|

(12.8) |

As a simple example, consider

| (12.9) |

Then the polyphase component filters are

![\begin{eqnarray*}

E_0(z) &=& 1 + 3z^{-1}\\ [5pt]

E_1(z) &=& 2 + 4z^{-1}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1963.png)

and

| (12.10) |

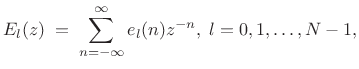

N-Channel Polyphase Decomposition

For the general case of arbitrary ![]() , the basic idea is to decompose

, the basic idea is to decompose

![]() into its periodically interleaved subsequences, as indicated

schematically in Fig.11.9. The polyphase decomposition into

into its periodically interleaved subsequences, as indicated

schematically in Fig.11.9. The polyphase decomposition into

![]() channels is given by

channels is given by

where the subphase filters are defined by

|

(12.12) |

with

|

(12.13) |

The signal

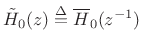

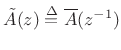

Type II Polyphase Decomposition

The polyphase decomposition of ![]() into

into ![]() channels in

(11.11) may be termed a ``type I'' polyphase decomposition. In

the ``type II'', or reverse polyphase decomposition, the powers

of

channels in

(11.11) may be termed a ``type I'' polyphase decomposition. In

the ``type II'', or reverse polyphase decomposition, the powers

of ![]() progress in the opposite direction:

progress in the opposite direction:

|

(12.14) |

We will see that we need type I for analysis filter banks and type II for synthesis filter banks in a general ``perfect reconstruction filter bank'' analysis/synthesis system.

Filtering and Downsampling, Revisited

Let's return to the example of §11.1.3, but

this time have the FIR lowpass filter h(n) be length ![]() ,

,

![]() . In this case, the

. In this case, the ![]() polyphase filters,

polyphase filters, ![]() , are

each length

, are

each length ![]() .12.2 Recall that

.12.2 Recall that

| (12.15) |

leading to the result shown in Fig.11.11.

Next, we commute the ![]() :

:![]() downsampler through the adders and

upsampled (stretched) polyphase filters

downsampler through the adders and

upsampled (stretched) polyphase filters ![]() to obtain

Fig.11.12. Commuting the downsampler through the

subphase filters

to obtain

Fig.11.12. Commuting the downsampler through the

subphase filters ![]() to obtain

to obtain ![]() is an example of a

multirate noble identity.

is an example of a

multirate noble identity.

Multirate Noble Identities

Figure 11.13 illustrates the so-called noble identities for

commuting downsamplers/upsamplers with ``sparse transfer functions''

that can be expressed a function of ![]() . Note that downsamplers

and upsamplers are linear, time-varying operators. Therefore,

operation order is important. Also note that adders and multipliers

(any memoryless operators) may be commuted across downsamplers and

upsamplers, as shown in Fig.11.14.

. Note that downsamplers

and upsamplers are linear, time-varying operators. Therefore,

operation order is important. Also note that adders and multipliers

(any memoryless operators) may be commuted across downsamplers and

upsamplers, as shown in Fig.11.14.

Critically Sampled Perfect Reconstruction Filter Banks

A Perfect Reconstruction (PR) filter bank is any filter bank

whose reconstruction is the original signal, possibly delayed, and

possibly scaled by a constant [287]. In this context,

critical sampling (also called ``maximal downsampling'') means

that the downsampling factor is the same as the number of filter

channels. For the STFT, this implies ![]() (with

(with ![]() allowed for

Portnoff windows).

allowed for

Portnoff windows).

As derived in Chapter 8, the Short-Time Fourier

Transform (STFT) is a PR filter bank whenever the Constant-OverLap-Add

(COLA) condition is met by the analysis window ![]() and the hop size

and the hop size

![]() . However, only the rectangular window case with no

zero-padding is critically sampled (OLA hop size = FBS downsampling

factor =

. However, only the rectangular window case with no

zero-padding is critically sampled (OLA hop size = FBS downsampling

factor = ![]() ). Perceptual audio compression algorithms such as MPEG

audio coding are based on critically sampled filter banks, for obvious

reasons. It is important to remember that we normally do not require

critical sampling for audio analysis, digital audio effects, and music

applications; instead, we normally need critical sampling only when

compression is a requirement. Thus, when compression is not a

requirement, we are normally interested in oversampled filter

banks. The polyphase representation is useful in that case as

well. In particular, we will obtain some excellent insights into the

aliasing cancellation that goes on in such downsampled filter

banks (including STFTs with hop sizes

). Perceptual audio compression algorithms such as MPEG

audio coding are based on critically sampled filter banks, for obvious

reasons. It is important to remember that we normally do not require

critical sampling for audio analysis, digital audio effects, and music

applications; instead, we normally need critical sampling only when

compression is a requirement. Thus, when compression is not a

requirement, we are normally interested in oversampled filter

banks. The polyphase representation is useful in that case as

well. In particular, we will obtain some excellent insights into the

aliasing cancellation that goes on in such downsampled filter

banks (including STFTs with hop sizes ![]() ), as the next section

makes clear.

), as the next section

makes clear.

Two-Channel Critically Sampled Filter Banks

Figure 11.15 shows a simple two-channel band-splitting filter bank,

followed by the corresponding synthesis filter bank which

reconstructs the original signal (we hope) from the two channels. The

analysis filter ![]() is a half-band lowpass filter, and

is a half-band lowpass filter, and ![]() is a complementary half-band highpass filter. The synthesis filters

is a complementary half-band highpass filter. The synthesis filters

![]() and

and ![]() are to be derived. Intuitively, we expect

are to be derived. Intuitively, we expect

![]() to be a lowpass that rejects the upper half-band due to the

upsampler by 2, and

to be a lowpass that rejects the upper half-band due to the

upsampler by 2, and ![]() should do the same but then also

reposition its output band as the upper half-band, which can be

accomplished by selecting the upper of the two spectral images in the

upsampler output.

should do the same but then also

reposition its output band as the upper half-band, which can be

accomplished by selecting the upper of the two spectral images in the

upsampler output.

The outputs of the two analysis filters in Fig.11.15 are

| (12.16) |

Using the results of §11.1, the signals become, after downsampling,

![$\displaystyle V_k(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{2}\left[X_k(z^{1/2}) + X_k(-z^{1/2})\right], \; k=0,1.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1988.png) |

(12.17) |

After upsampling, the signals become

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}[X_k(z) + X_k(-z)]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1990.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{1}{2}[H_k(z)X(z) + H_k(-z)X(-z)],\; k=0,1.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img1991.png) |

After substitutions and rearranging, we find that the output

For perfect reconstruction, we require the aliasing term to be zero. For ideal half-band filters cutting off at

In this case, synthesis filter

Referring again to (11.18), we see that we also need the

non-aliased term to be of the form

where

| (12.21) |

That is, for perfect reconstruction, we need, in addition to aliasing cancellation, that the non-aliasing term reduce to a constant gain

Let

![]() denote

denote ![]() . Then both constraints can be expressed in

matrix form as follows:

. Then both constraints can be expressed in

matrix form as follows:

![$\displaystyle \left[\begin{array}{cc} H_0 & H_1 \\ [2pt] {\tilde H}_0 & {\tilde H}_1 \end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{c} F_0 \\ [2pt] F_1 \end{array}\right]\eqsp \left[\begin{array}{c} c \\ [2pt] 0 \end{array}\right]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2013.png) |

(12.22) |

Substituting the aliasing-canceling choices for ![]() and

and ![]() from

(11.19) into the filtering-cancellation constraint (11.20), we

obtain

from

(11.19) into the filtering-cancellation constraint (11.20), we

obtain

The filtering-cancellation constraint is almost satisfied by ideal zero-phase half-band filters cutting off at

Amplitude-Complementary 2-Channel Filter Bank

A natural choice of analysis filters for our two-channel critically sampled filter bank is an amplitude-complementary lowpass/highpass pair, i.e.,

| (12.24) |

where we impose the unity dc gain constraint

Substituting the COLA constraint into the filtering and aliasing cancellation constraint (11.23) gives

![\begin{eqnarray*}

g\,z^{-d} &=& H_0(z)\left[1-H_0(-z)\right] - \left[1-H_0(z)\right]H_0(-z) \\ [5pt]

&=& H_0(z) - H_0(-z)\\ [5pt]

\;\longleftrightarrow\;\quad a(n) &=& h_0(n) - (-1)^n h_0(n) \\ [5pt]

&=& \left\{\begin{array}{ll}

0, & \hbox{$n$\ even} \\ [5pt]

2h_0(n), & \hbox{$n$\ odd} \\

\end{array} \right.

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2021.png)

Thus, we find that even-indexed terms of the impulse response are

unconstrained, since they subtract out in the constraint, while,

for perfect reconstruction, exactly one odd-indexed term

must be nonzero in the lowpass impulse response ![]() . The

simplest choice is

. The

simplest choice is

![]() .

.

Thus, we have derived that the lowpass-filter impulse-response for channel 0 can be anything of the form

or

| (12.26) |

etc. The corresponding highpass-filter impulse response is then

| (12.27) |

The first example (11.25) above goes with the highpass filter

| (12.28) |

and similarly for the other example.

The above class of amplitude-complementary filters can be characterized in general as follows:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_0(z) &=& E_0(z^2) + h_0(o) z^{-o}, \quad E_0(1)+h_0(o)\eqsp 1, \, \hbox{$o$\ odd}\\ [5pt]

H_1(z) &=& 1-H_0(z) \eqsp 1 - E_0(z^2) - h_0(o) z^{-o}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2028.png)

In summary, we see that an amplitude-complementary

lowpass/highpass analysis filter pair yields perfect reconstruction

(aliasing and filtering cancellation) when there is exactly one

odd-indexed term in the impulse response of ![]() .

.

Unfortunately, the channel filters are so constrained in form that it

is impossible to make a high quality lowpass/highpass pair. This

happens because ![]() repeats twice around the unit circle. Since

we assume real coefficients, the frequency response,

repeats twice around the unit circle. Since

we assume real coefficients, the frequency response,

![]() is magnitude-symmetric about

is magnitude-symmetric about

![]() as

well as

as

well as ![]() . This is not good since we only have one degree of

freedom,

. This is not good since we only have one degree of

freedom,

![]() , with which we can break the

, with which we can break the ![]() symmetry

to reduce the high-frequency gain and/or boost the low-frequency gain.

This class of filters cannot be expected to give high quality lowpass

or highpass behavior.

symmetry

to reduce the high-frequency gain and/or boost the low-frequency gain.

This class of filters cannot be expected to give high quality lowpass

or highpass behavior.

To achieve higher quality lowpass and highpass channel filters, we will need to relax the amplitude-complementary constraint (and/or filtering cancellation and/or aliasing cancellation) and find another approach.

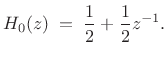

Haar Example

Before we leave the case of amplitude-complementary, two-channel,

critically sampled, perfect reconstruction filter banks, let's see

what happens when ![]() is the simplest possible lowpass filter

having unity dc gain, i.e.,

is the simplest possible lowpass filter

having unity dc gain, i.e.,

|

(12.29) |

This case is obtained above by setting

| (12.30) |

Choosing

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_0(z) &=& \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}z^{-1} \eqsp E_0(z^2)+z^{-1}E_1(z^2)\\ [5pt]

H_1(z) &=& 1-H_0(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2}z^{-1} \eqsp E_0(z^2)-z^{-1}E_1(z^2)\\ [5pt]

F_0(z) &=& \;\;\, H_1(-z) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}z^{-1} \eqsp \;\;\,H_0(z)\\ [5pt]

F_1(z) &=& -H_0(-z) \eqsp -\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}z^{-1} \eqsp -H_1(z).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2038.png)

Thus, both the analysis and reconstruction filter banks are scalings

of the familiar Haar filters (``sum and difference'' filters

![]() ). The frequency responses are

). The frequency responses are

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_0(e^{j\omega}) &=&\;\;\,F_0(e^{j\omega}) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}e^{-j\omega}\eqsp e^{-j\frac{\omega}{2}} \cos\left(\frac{\omega}{2}\right)\\ [5pt]

H_1(e^{j\omega}) &=& -F_0(e^{j\omega}) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{2}e^{-j\omega}\eqsp j e^{-j\frac{\omega}{2}} \sin\left(\frac{\omega}{2}\right)

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2040.png)

which are plotted in Fig.11.16.

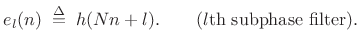

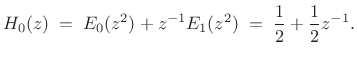

Polyphase Decomposition of Haar Example

Let's look at the polyphase representation for this example. Starting

with the filter bank and its reconstruction (see Fig.11.17), the

polyphase decomposition of ![]() is

is

|

(12.31) |

Thus,

| (12.32) |

We may derive polyphase synthesis filters as follows:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hat{X}(z) &=& \left[F_0(z)H_0(z) + F_1(z)H_1(z)\right] X(z)\\

&=& \left[\left(\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2}z^{-1}\right)H_0(z) + \left(-\frac{1}{2}+\frac{1}{2}z^{-1}\right)H_1(z)\right]X(z)\\

&=& \frac{1}{2}\left\{\left[H_0(z)-H_1(z)\right] + z^{-1}\left[H_0(z) + H_1(z)\right]\right\}X(z)

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2046.png)

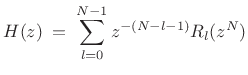

The polyphase representation of the filter bank and its reconstruction can now be drawn as in Fig.11.18. Notice that the reconstruction filter bank is formally the transpose of the analysis filter bank [263]. A filter bank that is inverted by its own transpose is said to be an orthogonal filter bank, a subject to which we will return §11.3.8.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/poly2chan}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2047.png) |

Commuting the downsamplers (using the noble identities from

§11.2.5), we obtain Figure 11.19. Since

![]() , this is simply the OLA form of an

STFT filter bank for

, this is simply the OLA form of an

STFT filter bank for ![]() , with

, with ![]() , and rectangular

window

, and rectangular

window

![]() . That is, the DFT size, window length, and hop

size are all 2, and both the DFT and its inverse are simply

sum-and-difference operations.

. That is, the DFT size, window length, and hop

size are all 2, and both the DFT and its inverse are simply

sum-and-difference operations.

Quadrature Mirror Filters (QMF)

The well studied subject of Quadrature Mirror Filters (QMF) is entered by imposing the following symmetry constraint on the analysis filters:

That is, the filter for channel 1 is constrained to be a

In the time domain, the QMF constraint (11.33) becomes

![]() , i.e., all odd-index coefficients are negated. If

, i.e., all odd-index coefficients are negated. If ![]() is a lowpass filter cutting off near

is a lowpass filter cutting off near

![]() (as is typical),

then

(as is typical),

then ![]() is a complementary highpass filter. The exact cut-off

frequency can be adjusted along with the roll-off rate to provide a

maximally constant frequency-response sum.

is a complementary highpass filter. The exact cut-off

frequency can be adjusted along with the roll-off rate to provide a

maximally constant frequency-response sum.

Two-channel QMFs have been around since at least 1976 [51], and appear to be the first critically sampled perfect reconstruction filter banks. Moreover, the Princen-Bradley filter bank, the initial foundation of MPEG audio as we now know it, was conceived as the Fourier dual of QMFs [214]. Historically, the term QMF applied only to two-channel filter banks having the QMF symmetry constraint (11.33). Today, the term ``QMF filter bank'' may refer to more general PR filter banks with any number of channels and not obeying (11.33) [287].

Combining the QMF symmetry constraint with the aliasing-cancellation constraints, given by

![\begin{eqnarray*}

F_0(z) &=& \quad\! H_1(-z) \eqsp \quad\! H_0(z)\\ [5pt]

F_1(z) &=& -H_0(-z) \eqsp -H_1(z),

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2055.png)

the perfect reconstruction requirement reduces to

Now, all four filters are determined by

It is easy to show using the polyphase representation of ![]() (see

[287]) that the only causal FIR QMF analysis filters yielding

exact perfect reconstruction are two-tap FIR filters of the

form

(see

[287]) that the only causal FIR QMF analysis filters yielding

exact perfect reconstruction are two-tap FIR filters of the

form

where ![]() and

and ![]() are constants, and

are constants, and ![]() and

and ![]() are integers.

Therefore, only weak channel filters are available in the QMF case

[

are integers.

Therefore, only weak channel filters are available in the QMF case

[

![]() ], as we saw in the amplitude-complementary case

above. On the other hand, very high quality IIR solutions are

possible. See [287, pp. 201-204] for details. In

practice, approximate ``pseudo QMF'' filters are more practical, which

only give approximate perfect reconstruction. We'll return to this

topic in §11.7.1.

], as we saw in the amplitude-complementary case

above. On the other hand, very high quality IIR solutions are

possible. See [287, pp. 201-204] for details. In

practice, approximate ``pseudo QMF'' filters are more practical, which

only give approximate perfect reconstruction. We'll return to this

topic in §11.7.1.

The scaled Haar filters, which we saw gave perfect reconstruction in the amplitude-complementary case, are also examples of a QMF filter bank:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_0(z) &=& 1 + z^{-1}\\ [5pt]

H_1(z) &=& 1 - z^{-1}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2063.png)

In this example, ![]() , and

, and ![]() .

.

Linear Phase Quadrature Mirror Filter Banks

Linear phase filters delay all frequencies by equal amounts, and this

is often a desirable property in audio and other applications. A

filter phase response is linear in ![]() whenever its impulse

response

whenever its impulse

response ![]() is symmetric, i.e.,

is symmetric, i.e.,

| (12.35) |

in which case the frequency response can be expressed as

| (12.36) |

Substituting this into the QMF perfect reconstruction constraint (11.34) gives

![$\displaystyle g\,e^{-j\omega d} \eqsp e^{-j\omega N}\left[ \left\vert H_0(e^{j\omega})\right\vert^2 - (-1)^N\left\vert H_0(e^{j(\pi-\omega)})\right\vert^2\right].$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2068.png) |

(12.37) |

When

![$\displaystyle g\,z^{-j\omega d} \eqsp e^{-j\omega N}\left[ \left\vert H_0(e^{j\omega})\right\vert^2 + \left\vert H_0(e^{j(\pi-\omega)}\right\vert^2\right].$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2069.png) |

(12.38) |

We see that perfect reconstruction is obtained in the linear-phase case whenever the analysis filters are power complementary. See [287] for further details.

Conjugate Quadrature Filters (CQF)

A class of causal, FIR, two-channel, critically sampled, exact perfect-reconstruction filter-banks is the set of so-called Conjugate Quadrature Filters (CQF). In the z-domain, the CQF relationships are

| (12.39) |

In the time domain, the analysis and synthesis filters are given by

![\begin{eqnarray*}

h_1(n) &=& -(-1)^n h_0(L-1-n) \\ [5pt]

f_0(n) &=& h_0(L-1-n) \\ [5pt]

f_1(n) &=& -(-1)^n h_0(n) \eqsp - h_1(L-1-n).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2071.png)

That is,

![]() for the lowpass channel, and each highpass

channel filter is a modulation of its lowpass counterpart by

for the lowpass channel, and each highpass

channel filter is a modulation of its lowpass counterpart by ![]() .

Again, all four analysis and synthesis filters are determined by the

lowpass analysis filter

.

Again, all four analysis and synthesis filters are determined by the

lowpass analysis filter ![]() . It can be shown that this is an

orthogonal filter bank. The analysis filters

. It can be shown that this is an

orthogonal filter bank. The analysis filters ![]() and

and

![]() are power complementary, i.e.,

are power complementary, i.e.,

| (12.40) |

or

| (12.41) |

where

denotes the

paraconjugate of

denotes the

paraconjugate of | (12.42) |

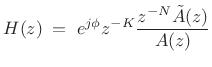

The power symmetric case was introduced by Smith and Barnwell in 1984 [272]. With the CQF constraints, (11.18) reduces to

Let

![]() , such that

, such that ![]() is a spectral factor of

the half-band filter

is a spectral factor of

the half-band filter ![]() (i.e.,

(i.e.,

![]() is a nonnegative power

response which is lowpass, cutting off near

is a nonnegative power

response which is lowpass, cutting off near

![]() ). Then,

(11.43) reduces to

). Then,

(11.43) reduces to

The problem of PR filter design has thus been reduced to designing one half-band filter

A simple design of an FIR half-band filter would be to window a sinc function:

![$\displaystyle p(n) \eqsp \frac{\hbox{sin}[\pi n/2]}{\pi n/2}w(n)$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2087.png) |

(12.45) |

where

Note that as a result of (11.43), the CQF filters are power complementary. That is, they satisfy

| (12.46) |

Also note that the filters

- FIR

- orthogonal

- linear phase

By relaxing ``orthogonality'' to ``biorthogonality'', it becomes possible to obtain FIR linear phase filters in a critically sampled, perfect reconstruction filter bank. (See §11.9.)

Orthogonal Two-Channel Filter Banks

Recall the reconstruction equation for the two-channel, critically sampled, perfect-reconstruction filter-bank:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hat{X}(z) &=& \frac{1}{2}[H_0(z)F_0(z) + H_1(z)F_1(z)]X(z)

\nonumber\\ [5pt]

&+& \frac{1}{2}[H_0(-z)F_0(z) + H_1(-z)F_1(z)]X(-z)

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2089.png)

This can be written in matrix form as

![$\displaystyle \hat{X}(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{array}{c} F_0(z) \\ [2pt] F_1(z) \end{array}\right]^{T} \left[\begin{array}{cc} H_0(z) & H_0(-z) \\ [2pt] H_1(z) & H_1(-z) \end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} X(z) \\ [2pt] X(-z) \end{array}\right]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2090.png) |

(12.47) |

where the above

| (12.48) |

where

denotes the

paraconjugate of

denotes the

paraconjugate of

It turns out orthogonal filter banks give perfect reconstruction filter banks for any number of channels. Orthogonal filter banks are also called paraunitary filter banks, which we'll study in polyphase form in §11.5 below. The AC matrix is paraunitary if and only if the polyphase matrix (defined in the next section) is paraunitary [287].

Perfect Reconstruction Filter Banks

We now consider filter banks with an arbitrary number of channels, and

ask under what conditions do we obtain a perfect reconstruction filter

bank? Polyphase analysis will give us the answer readily. Let's

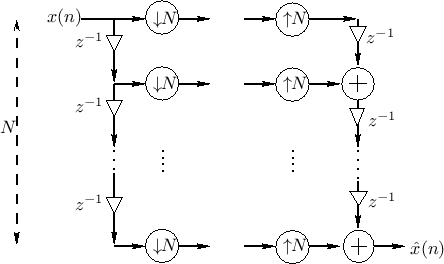

begin with the ![]() -channel filter bank in Fig.11.20. The

downsampling factor is

-channel filter bank in Fig.11.20. The

downsampling factor is ![]() . For critical sampling, we set

. For critical sampling, we set

![]() .

.

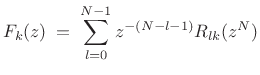

The next step is to expand each analysis filter ![]() into its

into its

![]() -channel ``type I'' polyphase representation:

-channel ``type I'' polyphase representation:

|

(12.49) |

or

![$\displaystyle \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{c} H_0(z) \\ [2pt] H_1(z) \\ [2pt] \vdots \\ [2pt] \!\!H_{N-1}(z)\!\!\end{array}\right]}_{\bold{h}(z)} = \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{cccc} E_{0,0}(z^N) & E_{0,1}(z^N) & \cdots & E_{0,N-1}(z^N) \\ E_{1,0}(z^N) & E_{1,1}(z^N) & \cdots & E_{1,N-1}(z^N)\\ \vdots & \vdots & \cdots & \vdots\\ \!\!E_{N-1,0}(z^N) & E_{N-1,1}(z^N) & \cdots & E_{N-1,N-1}(z^N) \!\! \end{array}\right]}_{\bold{E}(z^N)} \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{c} 1 \\ [2pt] z^{-1} \\ [2pt] \vdots \\ [2pt] \!\!z^{-(N-1)}\!\!\end{array}\right]}_{\bold{e}(z)}$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2099.png) |

(12.50) |

which we can write as

| (12.51) |

Similarly, expand the synthesis filters in a type II polyphase decomposition:

|

(12.52) |

or

![$\displaystyle \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{c} F_0(z) \\ [2pt] F_1(z) \\ [2pt] \vdots \\ [2pt] \!\!F_{N-1}(z)\!\!\end{array}\right]^T}_{\bold{f}^T(z)} \eqsp \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{c} \!\!z^{-(N-1)}\!\! \\ [2pt] \!\!z^{-(N-2)}\!\! \\ [2pt] \vdots \\ [2pt] 1\end{array}\right]^T}_{{\tilde{\bold{e}}}(z)} \underbrace{\left[\begin{array}{cccc} R_{0,0}(z^N) & R_{0,1}(z^N) & \cdots & R_{0,N-1}(z^N) \\ R_{1,0}(z^N) & R_{1,1}(z^N) & \cdots & R_{1,N-1}(z^N)\\ \vdots & \vdots & \cdots & \vdots\\ \!\!R_{N-1,0}(z^N) & R_{N-1,1}(z^N) & \cdots & R_{N-1,N-1}(z^N)\!\! \end{array}\right]}_{\bold{R}(z^N)}$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2102.png) |

(12.53) |

which we can write as

| (12.54) |

The polyphase representation can now be depicted as shown in

Fig.11.21. When ![]() , commuting the up/downsamplers gives

the result shown in Fig.11.22. We call

, commuting the up/downsamplers gives

the result shown in Fig.11.22. We call

![]() the

polyphase matrix.

the

polyphase matrix.

As we will show below, the above simplification can be carried out

more generally whenever ![]() divides

divides ![]() (e.g.,

(e.g.,

![]() ). In these cases

). In these cases

![]() becomes

becomes

![]() and

and

![]() becomes

becomes

![]() .

.

Simple Examples of Perfect Reconstruction

If we can arrange to have

| (12.55) |

then the filter bank will reduce to the simple system shown in Fig.11.23.

Thus, when ![]() and

and

![]() ,

we have a simple parallelizer/serializer,

which is perfect-reconstruction by inspection: Referring to

Fig.11.23, think of the input samples

,

we have a simple parallelizer/serializer,

which is perfect-reconstruction by inspection: Referring to

Fig.11.23, think of the input samples ![]() as ``filling'' a

length

as ``filling'' a

length ![]() delay line over

delay line over ![]() sample clocks. At time 0

, the

downsamplers and upsamplers ``fire'', transferring

sample clocks. At time 0

, the

downsamplers and upsamplers ``fire'', transferring ![]() (and

(and ![]() zeros) from the delay line to the output delay chain, summing with

zeros. Over the next

zeros) from the delay line to the output delay chain, summing with

zeros. Over the next ![]() clocks,

clocks, ![]() makes its way toward the

output, and zeros fill in behind it in the output delay chain.

Simultaneously, the input buffer is being filled with samples of

makes its way toward the

output, and zeros fill in behind it in the output delay chain.

Simultaneously, the input buffer is being filled with samples of

![]() . At time

. At time ![]() ,

, ![]() makes it to the output. At time

makes it to the output. At time ![]() ,

the downsamplers ``fire'' again, transferring a length

,

the downsamplers ``fire'' again, transferring a length ![]() ``buffer''

[

``buffer''

[![]() :

:![]() ] to the upsamplers. On the same clock pulse, the

upsamplers also ``fire'', transferring

] to the upsamplers. On the same clock pulse, the

upsamplers also ``fire'', transferring ![]() samples to the output delay

chain. The bottom-most sample [

samples to the output delay

chain. The bottom-most sample [

![]() ] goes out immediately

at time

] goes out immediately

at time ![]() . Over the next

. Over the next ![]() sample clocks, the length

sample clocks, the length ![]() output buffer will be ``drained'' and refilled by zeros.

Simultaneously, the input buffer will be replaced by new samples of

output buffer will be ``drained'' and refilled by zeros.

Simultaneously, the input buffer will be replaced by new samples of

![]() . At time

. At time ![]() , the downsamplers and upsamplers ``fire'', and

the process goes on, repeating with period

, the downsamplers and upsamplers ``fire'', and

the process goes on, repeating with period ![]() . The output of the

. The output of the

![]() -way parallelizer/serializer is therefore

-way parallelizer/serializer is therefore

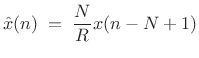

| (12.56) |

and we have perfect reconstruction.

Sliding Polyphase Filter Bank

When ![]() , there is no downsampling or upsampling, and the system

further reduces to the case shown in Fig.11.24. Working

backward along the output delay chain, the output sum can be written

as

, there is no downsampling or upsampling, and the system

further reduces to the case shown in Fig.11.24. Working

backward along the output delay chain, the output sum can be written

as

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hat{X}(z) &=& \left[z^{-0}z^{-(N-1)} + z^{-1}z^{-(N-2)} + z^{-2}z^{-(N-3)} + \cdots \right.\\

& & \left. + z^{-(N-2)}z^{-1} + z^{-(N-1)}z^{-0} \right] X(z)\\

&=& N z^{-(N-1)} X(z).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2121.png)

Thus, when ![]() , the output is

, the output is

| (12.57) |

and we again have perfect reconstruction.

Hopping Polyphase Filter Bank

When ![]() and

and ![]() divides

divides ![]() , we have, by a similar analysis,

, we have, by a similar analysis,

|

(12.58) |

which is again perfect reconstruction. Note the built-in overlap-add when

Sufficient Condition for Perfect Reconstruction

Above, we found that, for any integer

![]() which divides

which divides

![]() , a sufficient condition for perfect reconstruction is

, a sufficient condition for perfect reconstruction is

|

(12.59) |

and the output signal is then

|

(12.60) |

More generally, we allow any nonzero scaling and any additional delay:

where

|

(12.62) |

Thus, given any polyphase matrix

![]() , we can attempt to compute

, we can attempt to compute

![]() : If it is stable, we can use it to build a

perfect-reconstruction filter bank. However, if

: If it is stable, we can use it to build a

perfect-reconstruction filter bank. However, if

![]() is FIR,

is FIR,

![]() will typically be IIR. In §11.5 below, we will look at

paraunitary filter banks, for which

will typically be IIR. In §11.5 below, we will look at

paraunitary filter banks, for which

![]() is FIR and

paraunitary whenever

is FIR and

paraunitary whenever

![]() is.

is.

Necessary and Sufficient Conditions for Perfect Reconstruction

It can be shown [287] that the most general conditions for perfect reconstruction are that

![$\displaystyle \zbox {\bold{R}(z)\bold{E}(z) \eqsp c z^{-K} \left[\begin{array}{cc} \bold{0}_{(N-L)\times L} & z^{-1}\bold{I}_{N-L} \\ [2pt] \bold{I}_L & \bold{0}_{L \times (N-L)} \end{array}\right]}$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2132.png) |

(12.63) |

for some constant

Note that the more general form of

![]() above can be regarded as a (non-unique) square root of a vector unit delay, since

above can be regarded as a (non-unique) square root of a vector unit delay, since

![$\displaystyle \left[\begin{array}{cc} \bold{0}_{(N-L)\times L} & z^{-1}\bold{I}_{N-L} \\ [2pt] \bold{I}_L & \bold{0}_{L \times (N-L)} \end{array}\right]^2 \eqsp z^{-1}\bold{I}_N.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2136.png) |

(12.64) |

Thus, the general case is the same thing as

| (12.65) |

except for some channel swapping and an extra sample of delay in some channels.

Polyphase View of the STFT

As a familiar special case, set

| (12.66) |

where

![$\displaystyle \bold{W}_N^\ast[kn] \eqsp \left[e^{-j2\pi kn/N}\right]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2140.png) |

(12.67) |

The inverse of this polyphase matrix is then simply the inverse DFT matrix:

|

(12.68) |

Thus, the STFT (with rectangular window) is the simple special case of a perfect reconstruction filter bank for which the polyphase matrix is constant. It is also unitary; therefore, the STFT is an orthogonal filter bank.

The channel analysis and synthesis filters are, respectively,

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_k(z) &=& H_0(zW_N^k)\\ [5pt]

F_k(z) &=& F_0(zW_N^{-k})

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2142.png)

where

, and

, and

![$\displaystyle F_0(z)\eqsp H_0(z)\eqsp \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}z^{-n}\;\longleftrightarrow\;[1,1,\ldots,1]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2144.png) |

(12.69) |

corresponding to the rectangular window.

Looking again at the polyphase representation of the ![]() -channel

filter bank with hop size

-channel

filter bank with hop size ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() dividing

dividing ![]() , we have the system shown in Fig.11.25.

Following the same analysis as in §11.4.1 leads to the following

conclusion:

, we have the system shown in Fig.11.25.

Following the same analysis as in §11.4.1 leads to the following

conclusion:

Our analysis showed that the STFT using a rectangular window is

a perfect reconstruction filter bank for all

integer hop sizes in the set

![]() .

The same type of analysis can be applied to the STFT using the other

windows we've studied, including Portnoff windows.

.

The same type of analysis can be applied to the STFT using the other

windows we've studied, including Portnoff windows.

Example: Polyphase Analysis of the STFT with 50% Overlap, Zero-Padding, and a Non-Rectangular Window

Figure 11.26 illustrates how a window and a hop size other than

![]() can be introduced into the polyphase representation of the STFT.

The constant-overlap-add of the window

can be introduced into the polyphase representation of the STFT.

The constant-overlap-add of the window ![]() is implemented in the

synthesis delay chain (which is technically the

transpose of a tapped delay

line). The downsampling factor and window must be selected

together to give constant overlap-add, independent of the

choice of polyphase matrices

is implemented in the

synthesis delay chain (which is technically the

transpose of a tapped delay

line). The downsampling factor and window must be selected

together to give constant overlap-add, independent of the

choice of polyphase matrices

![]() and

and

![]() (shown here as the

(shown here as the

![]() and

and

![]() ).

).

Example: Polyphase Analysis of the Weighted Overlap Add Case: 50% Overlap, Zero-Padding, and a Non-Rectangular Window

We may convert the previous example to a weighted overlap-add

(WOLA) (§8.6) filter bank by replacing each ![]() by

by

![]() and introducing these gains also between the

and introducing these gains also between the

![]() and

upsamplers, as shown in Fig.11.27.

and

upsamplers, as shown in Fig.11.27.

Paraunitary Filter Banks

Paraunitary filter banks form an interesting subset of perfect

reconstruction (PR) filter banks. We saw above that we get a PR filter

bank whenever the

synthesis polyphase matrix

![]() times the

analysis polyphase matrix

times the

analysis polyphase matrix

![]() is the identity matrix

is the identity matrix ![]() , i.e., when

, i.e., when

|

(12.70) |

In particular, if

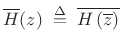

Paraconjugation is the generalization of the complex conjugate

transpose operation from the unit circle to the entire ![]() plane. A

paraunitary filter bank is therefore a generalization of an

orthogonal filter bank. Recall that an orthogonal filter bank

is one in which

plane. A

paraunitary filter bank is therefore a generalization of an

orthogonal filter bank. Recall that an orthogonal filter bank

is one in which

![]() is an orthogonal (or unitary) matrix, to

within a constant scale factor, and

is an orthogonal (or unitary) matrix, to

within a constant scale factor, and

![]() is its transpose (or

Hermitian transpose).

is its transpose (or

Hermitian transpose).

Lossless Filters

To motivate the idea of paraunitary filters, let's first review some properties of lossless filters, progressing from the simplest cases up to paraunitary filter banks:

A linear, time-invariant filter ![]() is said to be

lossless (or

allpass) if it preserves signal

energy. That is, if the input signal is

is said to be

lossless (or

allpass) if it preserves signal

energy. That is, if the input signal is ![]() , and the output

signal is

, and the output

signal is

![]() , then we have

, then we have

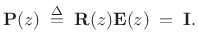

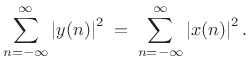

|

(12.71) |

In terms of the

| (12.72) |

Notice that only stable filters can be lossless since, otherwise,

It is straightforward to show that losslessness implies

| (12.73) |

That is, the frequency response must have magnitude 1 everywhere on the unit circle in the

| (12.74) |

and this form generalizes to

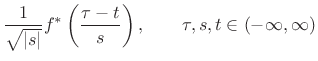

The paraconjugate of a transfer function may be defined as the

analytic continuation of the complex conjugate from the unit circle to

the whole ![]() plane:

plane:

|

(12.75) |

where

|

(12.76) |

in which the conjugation of

We refrain from conjugating ![]() in the definition of the paraconjugate

because

in the definition of the paraconjugate

because

![]() is not analytic in the complex-variables sense.

Instead, we invert

is not analytic in the complex-variables sense.

Instead, we invert ![]() , which is analytic, and which

reduces to complex conjugation on the unit circle.

, which is analytic, and which

reduces to complex conjugation on the unit circle.

The paraconjugate may be used to characterize allpass filters as follows:

A causal, stable, filter ![]() is allpass if and only if

is allpass if and only if

| (12.77) |

Note that this is equivalent to the previous result on the unit circle since

| (12.78) |

To generalize lossless filters to the multi-input, multi-output (MIMO) case, we must generalize conjugation to MIMO transfer function matrices.

A ![]() transfer function matrix

transfer function matrix

![]() is

said to be lossless

if it is stable and its frequency-response matrix

is

said to be lossless

if it is stable and its frequency-response matrix

![]() is

unitary. That is,

is

unitary. That is,

| (12.79) |

for all

|

(12.80) |

Note that

![]() is a

is a ![]() matrix

product of a

matrix

product of a ![]() times a

times a ![]() matrix. If

matrix. If ![]() , then

the rank must be deficient. Therefore, we must have

, then

the rank must be deficient. Therefore, we must have ![]() .

(There must be at least as many outputs as there are inputs, but it's

ok to have extra outputs.)

.

(There must be at least as many outputs as there are inputs, but it's

ok to have extra outputs.)

A lossless ![]() transfer function matrix

transfer function matrix

![]() is paraunitary,

i.e.,

is paraunitary,

i.e.,

| (12.81) |

Thus, every paraunitary matrix transfer function is unitary on the unit circle for all

Lossless Filter Examples

The simplest lossless filter is a unit-modulus gain

| (12.82) |

where

A lossless FIR filter can only consist of a single nonzero tap:

for some fixed integer

Every finite-order, single-input, single-output (SISO), lossless IIR filter (recursive allpass filter) can be written as

|

(12.84) |

where

. The polynomial

. The polynomial

The normalized DFT matrix is an ![]() order zero paraunitary

transformation. This is because the normalized DFT matrix,

order zero paraunitary

transformation. This is because the normalized DFT matrix,

![]() ,

,

![]() , where

, where

![]() , is a unitary matrix:

, is a unitary matrix:

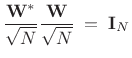

|

(12.85) |

Properties of Paraunitary Filter Banks

Paraunitary systems are essentially multi-input, multi-output (MIMO)

allpass filters. Let

![]() denote the

denote the ![]() matrix transfer

function of a paraunitary system. In the square case (

matrix transfer

function of a paraunitary system. In the square case (![]() ), the

matrix determinant,

), the

matrix determinant,

![]() , is an allpass filter.

Therefore, if a square

, is an allpass filter.

Therefore, if a square

![]() contains FIR elements, its determinant

is a simple delay:

contains FIR elements, its determinant

is a simple delay:

![]() for some integer

for some integer ![]() .

.

An ![]() -channel analysis filter bank can be viewed as an

-channel analysis filter bank can be viewed as an ![]() MIMO filter:

MIMO filter:

![$\displaystyle \bold{H}(z) \eqsp \left[\begin{array}{c} H_1(z) \\ [2pt] H_2(z) \\ [2pt] \vdots \\ [2pt] H_N(z)\end{array}\right]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2206.png) |

(12.86) |

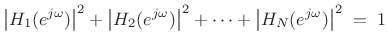

A paraunitary filter bank must therefore satisfy

| (12.87) |

More generally, we allow paraunitary filter banks to scale and/or delay the input signal:

| (12.88) |

where

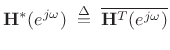

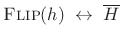

We can note the following properties of paraunitary filter banks:

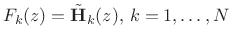

- The synthesis filter bank is simply the paraconjugate of the

analysis filter bank:

(12.89)

That is, since the paraconjugate is the inverse of a paraunitary filter matrix, it is exactly what we need for perfect reconstruction. - The channel filters

are power complementary:

are power complementary:

(12.90)

This follows immediately from looking at the paraunitary property on the unit circle. - When

is FIR, the corresponding synthesis filter matrix

is FIR, the corresponding synthesis filter matrix

is also FIR.

is also FIR.

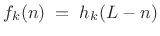

- When

is FIR, each synthesis filter,

is FIR, each synthesis filter,

, is simply the

, is simply the

of its corresponding

analysis filter

of its corresponding

analysis filter

:

:

(12.91)

where is the filter length. (When the filter coefficients are

complex,

is the filter length. (When the filter coefficients are

complex,

includes a complex conjugation as well.) This

follows from the fact that paraconjugating an FIR filter amounts to

simply flipping (and conjugating) its coefficients. As we observed in

(11.83) above (§11.5.2), only trivial FIR filters of

the form

includes a complex conjugation as well.) This

follows from the fact that paraconjugating an FIR filter amounts to

simply flipping (and conjugating) its coefficients. As we observed in

(11.83) above (§11.5.2), only trivial FIR filters of

the form

can be paraunitary in the

single-input, single-output (SISO) case. In the MIMO case, on the

other hand, paraunitary systems can be composed of FIR filters of any

order.

can be paraunitary in the

single-input, single-output (SISO) case. In the MIMO case, on the

other hand, paraunitary systems can be composed of FIR filters of any

order.

- FIR analysis and synthesis filters in paraunitary filter banks

have the same amplitude response. This follows from the fact

that

, i.e., flipping an FIR filter

impulse response

, i.e., flipping an FIR filter

impulse response  conjugates the frequency response, which does

not affect its amplitude response

conjugates the frequency response, which does

not affect its amplitude response

.

.

- The polyphase matrix

for any FIR paraunitary perfect

reconstruction filter bank can be written as the product of a

paraunitary and a unimodular matrix, where a

unimodular polynomial matrix

for any FIR paraunitary perfect

reconstruction filter bank can be written as the product of a

paraunitary and a unimodular matrix, where a

unimodular polynomial matrix

is any square

polynomial matrix having a constant nonzero

determinant. For example,

is any square

polynomial matrix having a constant nonzero

determinant. For example, ![$\displaystyle \bold{U}(z) \eqsp

\left[\begin{array}{cc} 1+z^3 & z^2 \\ [2pt] z & 1 \end{array}\right] $](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2221.png)

is unimodular. See [287, p. 663] for further details.

Examples

Consider the Haar filter bank discussed in §11.3.3, for which

![$\displaystyle \bold{H}(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{c} 1+z^{-1} \\ [2pt] 1-z^{-1} \end{array}\right].$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2222.png) |

(12.92) |

The paraconjugate of

![$\displaystyle {\tilde {\bold{H}}}(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cc} 1+z & 1 - z \end{array}\right]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2223.png) |

(12.93) |

so that

![$\displaystyle {\tilde {\bold{H}}}(z) \bold{H}(z) \eqsp \frac{1}{2} \left[\begin{array}{cc} 1+z & 1 - z \end{array}\right] \left[\begin{array}{c} 1+z^{-1} \\ [2pt] 1-z^{-1} \end{array}\right] \eqsp 1.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2224.png) |

(12.94) |

Thus, the Haar filter bank is paraunitary. This is true for any power-complementary filter bank, since when

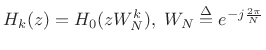

Filter Banks Equivalent to STFTs

We now turn to various practical examples of perfect reconstruction filter banks, with emphasis on those using FFTs in their implementation (i.e., various STFT filter banks).

Figure 11.28 illustrates a generic filter bank with ![]() channels,

much like we derived in §9.3.

The analysis filters

channels,

much like we derived in §9.3.

The analysis filters ![]() ,

,

![]() are bandpass filters

derived from a lowpass prototype

are bandpass filters

derived from a lowpass prototype ![]() by modulation (e.g.,

by modulation (e.g.,

), as

shown in the right portion of the figure. The channel signals

), as

shown in the right portion of the figure. The channel signals

![]() are given by the convolution of the input signal with

the

are given by the convolution of the input signal with

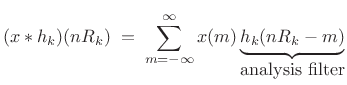

the ![]() th channel impulse response:

th channel impulse response:

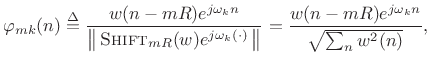

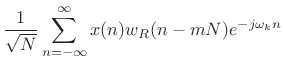

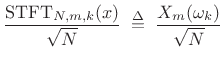

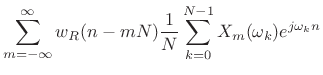

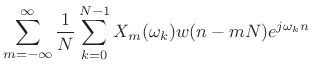

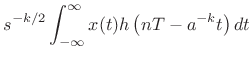

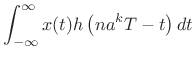

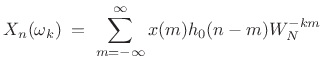

From Chapter 9, we recognize this expression as the sliding-window STFT, where

Suppose the analysis window ![]() (flip of the baseband-filter impulse

response

(flip of the baseband-filter impulse

response ![]() ) is length

) is length ![]() . Then in the context of overlap-add

processors (Chapter 8),

. Then in the context of overlap-add

processors (Chapter 8), ![]() is a Portnoff

window, and implementing the window with a length

is a Portnoff

window, and implementing the window with a length ![]() FFT requires

that the windowed data frame be time-aliased down to length

FFT requires

that the windowed data frame be time-aliased down to length

![]() prior to taking a length

prior to taking a length ![]() FFT (see §9.7). We can

obtain this same result via polyphase analysis, as elaborated in the

next section.

FFT (see §9.7). We can

obtain this same result via polyphase analysis, as elaborated in the

next section.

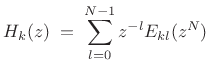

Polyphase Analysis of Portnoff STFT

Consider the ![]() th filter-bank channel filter

th filter-bank channel filter

| (12.96) |

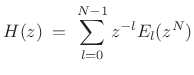

The impulse-response

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_{0}(z) & = & \sum_{l=0}^{N-1} z^{-l}E_l(z^{N}) \\ [5pt]

H_{k}(z) & = & \sum_{l=0}^{N-1} (zW_N^k)^{-l} E_l[(z W_N^k)^{N}] \\ [5pt]

& = & \sum_{l=0}^{N-1} z^{-l} E_l(z^{N}) W_N^{-kl}.

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2238.png)

Consequently,

![\begin{eqnarray*}

H_{k}(z)X(z) & = & \sum_{l=0}^{N-1} z^{-l} E_l(z^{N})X(z) W_N^{-kl} \\

\left[\begin{array}{c}

H_{0}(z) \\

\ldots \\

H_{N-1}(z) \end{array} \right]

& = & \left[\begin{array}{ccc}

& & \\

& W_N^{-kl} & \\

& & \end{array} \right]

\left[\begin{array}{c}

E_0(z^N) z^{-0} X(z) \\

\ldots \\

E_{N-1}(z^N) z^{-(N-1)} X(z) \end{array}

\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2239.png)

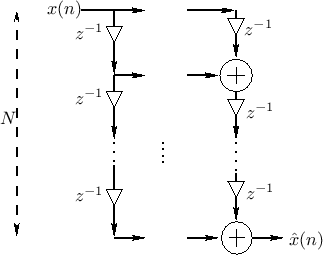

If ![]() is a good

is a good ![]() th-band lowpass, the subband signals

th-band lowpass, the subband signals

![]() are bandlimited to a region of width

are bandlimited to a region of width ![]() . As a result,

there is negligible aliasing when we downsample each of the subbands

by

. As a result,

there is negligible aliasing when we downsample each of the subbands

by ![]() . Commuting the downsamplers to get an efficient implementation

gives Fig.11.29.

. Commuting the downsamplers to get an efficient implementation

gives Fig.11.29.

First note that if

![]() for all

for all ![]() , the system of

Fig.11.29 reduces to a rectangularly windowed STFT in which the

window length

, the system of

Fig.11.29 reduces to a rectangularly windowed STFT in which the

window length ![]() equals the DFT length

equals the DFT length ![]() . The downsamplers

``hold off'' the DFT until the length 3 delay line fills with new

input samples, then it ``fires'' to produce a spectral frame. A new

spectral frame is produced after every third sample of input data is

received.

. The downsamplers

``hold off'' the DFT until the length 3 delay line fills with new

input samples, then it ``fires'' to produce a spectral frame. A new

spectral frame is produced after every third sample of input data is

received.

In the more general case in which ![]() are nontrivial filters,

such as

are nontrivial filters,

such as

![]() , for example, they can be seen to compute the

equivalent of a time aliased windowed input frame, such as

, for example, they can be seen to compute the

equivalent of a time aliased windowed input frame, such as

![]() . This follows because the filters operate on the

downsampled input stream, so that the filter coefficients operate on

signal samples separated by

. This follows because the filters operate on the

downsampled input stream, so that the filter coefficients operate on

signal samples separated by ![]() samples. The linear combination of

these samples by the filter implements the time-aliased windowed data

frame in a Portnoff-windowed overlap-add STFT. Taken together, the

polyphase filters

samples. The linear combination of

these samples by the filter implements the time-aliased windowed data

frame in a Portnoff-windowed overlap-add STFT. Taken together, the

polyphase filters ![]() compute the appropriately time-aliased data

frame windowed by

compute the appropriately time-aliased data

frame windowed by

![]() .

.

In the overlap-add interpretation of Fig.11.29, the window is

hopped by ![]() samples. While this was the entire window length in

the rectangular window case (

samples. While this was the entire window length in

the rectangular window case (![]() ), it is only a portion of the

effective frame length

), it is only a portion of the

effective frame length ![]() when the analysis filters have order 1 or

greater.

when the analysis filters have order 1 or

greater.

MPEG Filter Banks

This section provides some highlights of the history of filter banks used for perceptual audio coding (MPEG audio). For a more complete introduction and discussion of MPEG filter banks, see, e.g., [16,273].

Pseudo-QMF Cosine Modulation Filter Bank

Section 11.3.5 introduced two-channel quadrature mirror filter banks (QMF). QMFs were shown to provide a particular class of perfect reconstruction filter banks. We found, however, that the quadrature mirror constraint on the analysis filters,

| (12.97) |

was rather severe in that linear-phase FIR implementations only exist in the two-tap case

The Pseudo-QMF (PQMF) filter bank is a ``near perfect

reconstruction'' filter bank in which aliasing cancellation occurs

only between adjacent bands [194,287]. The PQMF

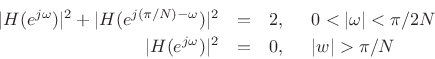

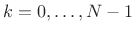

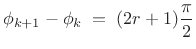

filters commonly used in perceptual audio coders employ bandpass

filters with stop-band attenuation near ![]() dB, so the neglected

bands (which alias freely) are not significant. An outline of the

design procedure is as follows:

dB, so the neglected

bands (which alias freely) are not significant. An outline of the

design procedure is as follows:

- Design a lowpass prototype window,

, with length

, with length  ,

,

- The lowpass design is

constrained to give aliasing cancellation in neighboring subbands:

- The filter bank analysis filters

are cosine modulations of

are cosine modulations of

:

:

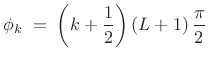

![$\displaystyle h_k(n) \eqsp h(n)\hbox{cos}\left[\left(k+\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(n-\frac{M-1}{2}\right)\frac{\pi}{N} + \phi_k\right],$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2254.png)

(12.98)

, where the phases are restricted according to

, where the phases are restricted according to

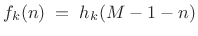

(12.99)

again for aliasing cancellation. - Since it is an orthogonal filter bank by construction,

the synthesis filters are simply the time-reverse of the analysis filters:

(12.100)

Perfect Reconstruction Cosine Modulated Filter Banks

By changing the phases ![]() , the pseudo-QMF filter bank can yield

perfect reconstruction:

, the pseudo-QMF filter bank can yield

perfect reconstruction:

|

(12.101) |

where

If ![]() , then this is the

oddly stacked Princen-Bradley filter bank

and the analysis filters are related by cosine modulations of

the lowpass prototype:

, then this is the

oddly stacked Princen-Bradley filter bank

and the analysis filters are related by cosine modulations of

the lowpass prototype:

![$\displaystyle f_k(n) \eqsp h(n)\hbox{cos}\left[\left(n+\frac{N+1}{2}\right)\left(k+\frac{1}{2}\right)\frac{\pi}{N}\right],\quad k=0,\ldots,N-1$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2262.png) |

(12.102) |

However, the length of the filters

| (12.103) |

The parameter

MPEG Layer III Filter Bank

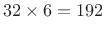

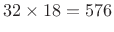

MPEG 1 and 2, Layer III is popularly known as ``MP3 format.'' The original MPEG 1 and 2, Layers I and II, based on the MUSICAM coder, contained only 32 subbands, each band approximately 650 Hz wide, implemented using a length 512 lowpass-prototype window, lapped (``time aliased'') by factor of 512/32 = 16, thus yielding 32 real bands with 96 dB of stop-band rejection, and having a hop size of 32 samples [149, §4.1.1]. It was found, however, that a higher coding gain was obtained using a finer frequency resolution. As a result, the MPEG 1&2 Layer III coder (based on the ASPEC coder from AT&T), appended a Princen-Bradley filter bank [214] having 6 to 18 subbands to the output of each subband of the 32-channel PQMF cosine-modulated analysis filter bank [149, § 4.1.2]. The number of sub-bands and window shape were chosen to be signal-dependent as follows:

- Transients use

subbands, corresponding to relatively

high time resolution and low frequency resolution.

subbands, corresponding to relatively

high time resolution and low frequency resolution.

- Steady-state tones use

subbands, corresponding to higher

frequency resolution and lower time resolution relative to

transients.12.3

subbands, corresponding to higher

frequency resolution and lower time resolution relative to

transients.12.3

- The encoder generates a function called the perceptual entropy (PE) which tells the coder when to switch resolutions.

The MPEG AAC coder is often regarded as providing nearly twice the

compression ratio of ``MP3'' (MPEG 1-2 Layer III) coding at the same

quality level.12.4 MPEG AAC

introduced a new MDCT filter bank that adaptively switches between 128

and 1024 bands (length 256 and 2048 FFT windows, using 50% overlap)

[149, §4.1.6]. The nearly doubled number of frequency

bands available for coding steady-state signal intervals contributed

much to the increased coding gain of AAC over MP3. The 128-1024 MDCT

filter bank in AAC is also considerably simpler than the hierarchical

![]() -

-![]() MP3 filter bank, without requiring the ``cross-talk

aliasing reduction'' needed by the PQMF/MDCT hierarchical filter bank

of MP3 [149, §4.1.6].

MP3 filter bank, without requiring the ``cross-talk

aliasing reduction'' needed by the PQMF/MDCT hierarchical filter bank

of MP3 [149, §4.1.6].

The MPEG-4 audio compression standard (there was no MPEG-3), included a new transform coder based on the AAC filter bank [149, §4.1.7].

See, e.g., [16,273] for much more on MPEG coders and related topics. Chapter 4 of [149] contains an excellent summary of MPEG, Sony ATRAC, and Dolby AC-n coders up to 1998.

Review of STFT Filterbanks

Let's take a look at some of the STFT processors we've seen before, now viewed as polyphase filter banks. Since they all use FFTs to perform overlap-add decompositions of spectra, they are all efficient, but most are oversampled in time and/or frequency as ``filter banks'' go. Oversampling is usually preferred outside of a compression context, and normally required when spectral modifications are to be performed. The STFT also computes a uniform filter bank, but it can be used as the basis for a variety of non-uniform filter banks, as discussed in §10.7, to give frequency resolution more like that of hearing (§7.3).

For each selected STFT example below, a list of filter-bank properties

is listed, followed by some discussion. Most of the properties are

determined by the choice of FFT window ![]() and FFT hop size

and FFT hop size ![]() .

.

STFT, Rectangular Window, No Overlap

- Perfect reconstruction

- Critically sampled (relies on aliasing cancellation)

- Poor channel isolation (

dB)

dB)

- Not robust to filter-bank modifications

STFT, Rectangular Window, 50% Overlap

- Perfect reconstruction

- Oversampled by 2 (less reliant on aliasing cancellation)

- Poor channel isolation (

dB)

dB)

- Not very robust to filter-bank modifications, but better

STFT, Triangular Window, 50% Overlap

- Perfect reconstruction

- Oversampled by 2

- Better channel isolation (

dB)

dB)

- Moderately robust to filter-bank modifications

STFT, Hamming Window, 75% Overlap

- Perfect reconstruction

- Oversampled by 4

- Aliasing from side lobes only

- Good channel isolation (

dB)

dB)

- Moderately robust to filter-bank modifications

STFT, Kaiser Window, Beta=10, 90% Overlap

- Approximate perfect reconstruction (side lobes controlled by

)

)

- Oversampled by

- Excellent channel isolation (

dB)

dB)

- Very robust to filter-bank modifications

- Aliasing from side lobes only

Sliding FFT (Maximum Overlap), Any Window, Zero-Padded by 5

- Perfect reconstruction (always true when hop-size

)

)

- Oversampled by

, where

, where

= window length (time-domain oversampling factor)

= window length (time-domain oversampling factor)

- 5 = zero-padding factor (frequency-domain oversampling factor)

- Excellent channel isolation (set by window side lobes)

- Extremely robust to filter-bank modifications

- No aliasing to cancel!

Wavelet Filter Banks

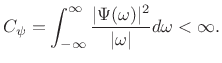

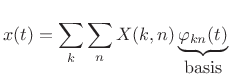

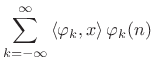

Let's now approach filter-bank derivation from a ``Hilbert space'' (geometric) point of view. This is the most natural setting for the study of wavelet filter banks [291,287].

Geometric Signal Theory

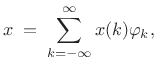

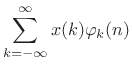

In general, signals can be expanded as a linear combination

of orthonormal basis signals ![]() [264]. In the

discrete-time case, this can be expressed as

[264]. In the

discrete-time case, this can be expressed as

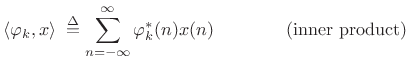

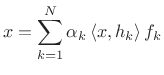

where the coefficient of projection of

|

(12.105) |

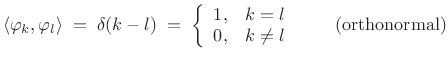

and the basis signals are orthonormal:

|

(12.106) |

The signal expansion (11.104) can be interpreted geometrically as a sum of orthogonal projections of

A set of signals

![]() is said to be

a biorthogonal basis set if any signal

is said to be

a biorthogonal basis set if any signal ![]() can be represented

as

can be represented

as

|

(12.107) |

where

The following examples illustrate the Hilbert space point of view for various familiar cases of the Fourier transform and STFT. A more detailed introduction appears in Book I [264].

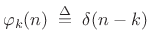

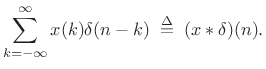

Natural Basis

The natural basis for a discrete-time signal ![]() is the set

of shifted impulses:

is the set

of shifted impulses:

![$\displaystyle \varphi_k \isdefs [\ldots, 0,\underbrace{1}_{k^{\hbox{\tiny th}}},0,\ldots],$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2291.png) |

(12.108) |

or,

|

(12.109) |

for all integers

| (12.110) |

so that the expansion of

|

(12.111) |

i.e.,

|

|||

|

This expansion was used in Book II [263] to derive the impulse-response representation of an arbitrary linear, time-invariant filter.

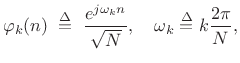

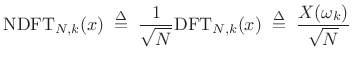

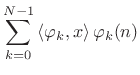

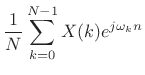

Normalized DFT Basis for

The Normalized Discrete Fourier Transform (NDFT) (introduced in

Book I [264]) projects the signal ![]() onto

onto ![]() discrete-time sinusoids of length

discrete-time sinusoids of length ![]() , where the sinusoids are

normalized to have unit

, where the sinusoids are

normalized to have unit ![]() norm:

norm:

|

(12.112) |

and

|

|||

|

and the expansion of

|

|||

|

|||

for

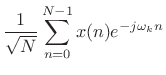

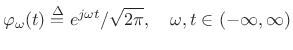

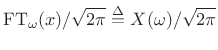

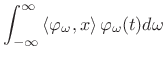

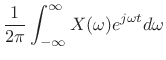

Normalized Fourier Transform Basis

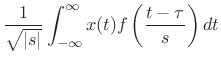

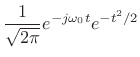

The Fourier transform projects a continuous-time signal ![]() onto an

infinite set of continuous-time complex sinusoids

onto an