Alternative Realizations

For actually implementing the example digital filter, we have only seen the difference equation

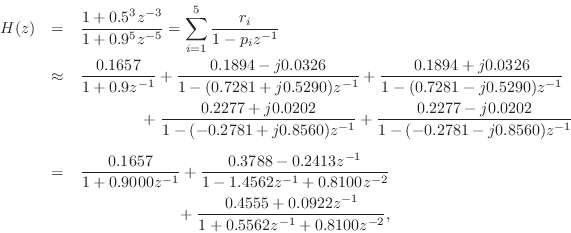

We will now illustrate the computation of a parallel second-order

realization of our example filter

![]() . As discussed above in §3.11, this filter has five

poles and three zeros. We can use the partial fraction

expansion (PFE), described in §6.8, to expand the transfer

function into a sum of five first-order terms:

. As discussed above in §3.11, this filter has five

poles and three zeros. We can use the partial fraction

expansion (PFE), described in §6.8, to expand the transfer

function into a sum of five first-order terms:

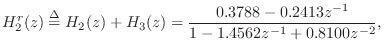

where, in the last step, complex-conjugate one-pole sections are

combined into real second-order sections. Also, numerical values are

given to four decimal places (so `![]() ' is replaced by `

' is replaced by `![]() ' in

the second line). In the following subsections, we will plot the

impulse responses and frequency responses of the first- and

second-order filter sections above.

' in

the second line). In the following subsections, we will plot the

impulse responses and frequency responses of the first- and

second-order filter sections above.

First-Order Parallel Sections

Figure 3.13 shows the impulse response of the real one-pole section

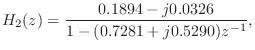

Figure 3.15 shows the impulse response of the complex one-pole section

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcir2}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img362.png) |

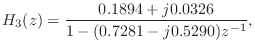

The complex-conjugate section,

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcir3}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img365.png) |

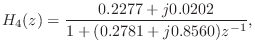

Figure 3.19 shows the impulse response of the complex one-pole section

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcir4}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img371.png) |

Parallel, Real, Second-Order Sections

Figure 3.21 shows the impulse response of the real two-pole section

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arir2}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img375.png) |

Finally, Fig.3.23 gives the impulse response of the real two-pole section

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arir3}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img378.png) |

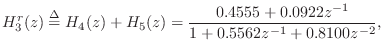

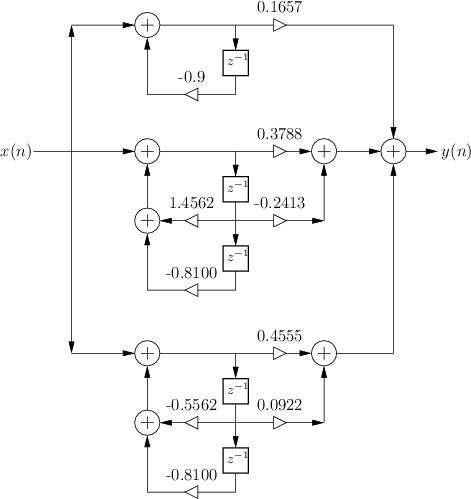

Parallel Second-Order Signal Flow Graph

Figure 3.25 shows the signal flow graph for the implementation of our

example filter using parallel second-order sections (with one

first-order section since the number of poles is odd). This is the

same filter as that shown in Fig.3.1 with ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The second-order sections are

special cases of the ``biquad'' filter section, which is often

implemented in software (and chip) libraries. Any digital filter can

be implemented as a sum of parallel biquads by finding its transfer

function and computing the partial fraction expansion.

. The second-order sections are

special cases of the ``biquad'' filter section, which is often

implemented in software (and chip) libraries. Any digital filter can

be implemented as a sum of parallel biquads by finding its transfer

function and computing the partial fraction expansion.

|

|

The two second-order biquad sections in Fig.3.25 are in so-called ``Direct-Form II'' (DF-II) form. In Chapter 9, a total of four direct-form filter implementations will be discussed, along with some other commonly used implementation structures. In particular, it is explained there why Transposed Direct-Form II (TDF-II) is usually a better choice of implementation structure for IIR filters when numerical dynamic range is limited (as it is in fixed-point ``DSP chips''). Figure 3.26 shows how our example looks using TDF-II biquads in place of the DF-II biquads of Fig.3.25.

Series, Real, Second-Order Sections

Converting the difference equation

![]() to a series bank of real first- and second-order

sections is comparatively easy. In this case, we do not need a full

blown partial fraction expansion. Instead, we need only factor the

numerator and denominator of the transfer function into first- and/or

second-order terms. Since a second-order section can accommodate up

to two poles and two zeros, we must decide how to group pairs of poles

with pairs of zeros. Furthermore, since the series sections can be

implemented in any order, we must choose the section ordering. Both

of these choices are normally driven in practice by numerical

considerations. In fixed-point implementations, the poles and zeros

are grouped such that dynamic range requirements are minimized.

Similarly, the section order is chosen so that the intermediate

signals are well scaled. For example, internal overflow is more likely

if all of the large-gain sections appear before the low-gain sections.

On the other hand, the signal-to-quantization-noise ratio will

deteriorate if all of the low-gain sections are placed before the

higher-gain sections. For further reading on numerical considerations

for digital filter sections, see, e.g., [103].

to a series bank of real first- and second-order

sections is comparatively easy. In this case, we do not need a full

blown partial fraction expansion. Instead, we need only factor the

numerator and denominator of the transfer function into first- and/or

second-order terms. Since a second-order section can accommodate up

to two poles and two zeros, we must decide how to group pairs of poles

with pairs of zeros. Furthermore, since the series sections can be

implemented in any order, we must choose the section ordering. Both

of these choices are normally driven in practice by numerical

considerations. In fixed-point implementations, the poles and zeros

are grouped such that dynamic range requirements are minimized.

Similarly, the section order is chosen so that the intermediate

signals are well scaled. For example, internal overflow is more likely

if all of the large-gain sections appear before the low-gain sections.

On the other hand, the signal-to-quantization-noise ratio will

deteriorate if all of the low-gain sections are placed before the

higher-gain sections. For further reading on numerical considerations

for digital filter sections, see, e.g., [103].

Next Section:

Summary

Previous Section:

Pole-Zero Analysis

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arir1}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img359.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arfr1}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img360.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcfr2}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img363.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcfr3}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img366.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arcfr4}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img372.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arfr2}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img376.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/arfr3}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img379.png)