Partial Fraction Expansion

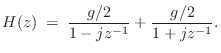

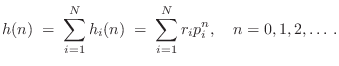

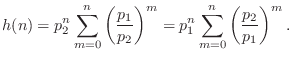

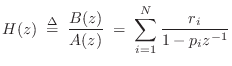

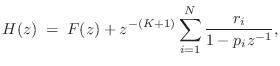

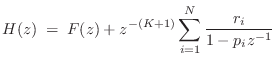

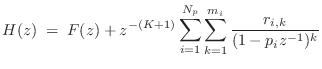

An important tool for inverting the z transform and converting among digital filter implementation structures is the partial fraction expansion (PFE). The term ``partial fraction expansion'' refers to the expansion of a rational transfer function into a sum of first and/or second-order terms. The case of first-order terms is the simplest and most fundamental:

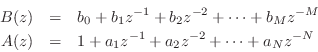

where

and ![]() . (The case

. (The case ![]() is addressed in the next section.)

The denominator coefficients

is addressed in the next section.)

The denominator coefficients ![]() are called the poles of the

transfer function, and each numerator

are called the poles of the

transfer function, and each numerator ![]() is called the

residue of pole

is called the

residue of pole ![]() . Equation (6.7) is general only if the poles

. Equation (6.7) is general only if the poles

![]() are distinct. (Repeated poles are addressed in

§6.8.5 below.) Both the poles and their residues may be

complex. The poles may be found by factoring the polynomial

are distinct. (Repeated poles are addressed in

§6.8.5 below.) Both the poles and their residues may be

complex. The poles may be found by factoring the polynomial ![]() into first-order terms,7.4e.g., using the roots function in matlab.

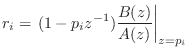

The residue

into first-order terms,7.4e.g., using the roots function in matlab.

The residue ![]() corresponding to pole

corresponding to pole ![]() may be found

analytically as

may be found

analytically as

when the poles

Note that in Eq.![]() (6.8), there is always a pole-zero cancellation at

(6.8), there is always a pole-zero cancellation at

![]() . That is, the term

. That is, the term

![]() is always cancelled by an

identical term in the denominator of

is always cancelled by an

identical term in the denominator of ![]() , which must exist because

, which must exist because

![]() has a pole at

has a pole at ![]() . The residue

. The residue ![]() is simply the

coefficient of the one-pole term

is simply the

coefficient of the one-pole term

![]() in the partial

fraction expansion of

in the partial

fraction expansion of ![]() at

at ![]() . The transfer function

is

. The transfer function

is

![]() , in the limit, as

, in the limit, as ![]() .

.

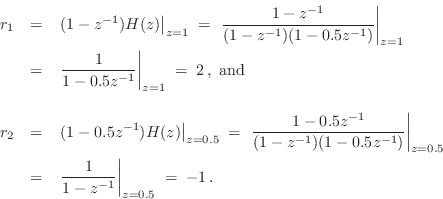

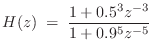

Example

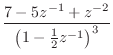

Consider the two-pole filter

We thus conclude that

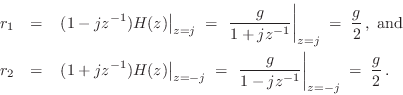

Complex Example

To illustrate an example involving complex poles, consider the filter

Thus,

A more elaborate example of a partial fraction expansion into complex one-pole sections is given in §3.12.1.

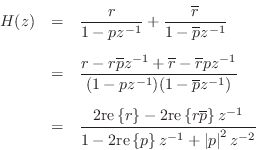

PFE to Real, Second-Order Sections

When all coefficients of ![]() and

and ![]() are real (implying that

are real (implying that

![]() is the transfer function of

a real filter), it will

always happen that the complex one-pole filters will occur in

complex conjugate pairs. Let

is the transfer function of

a real filter), it will

always happen that the complex one-pole filters will occur in

complex conjugate pairs. Let ![]() denote any one-pole

section in the PFE of Eq.

denote any one-pole

section in the PFE of Eq.![]() (6.7). Then if

(6.7). Then if ![]() is complex and

is complex and ![]() describes a real filter, we will also find

describes a real filter, we will also find

![]() somewhere among

the terms in the one-pole expansion. These two terms can be paired to

form a real second-order section as follows:

somewhere among

the terms in the one-pole expansion. These two terms can be paired to

form a real second-order section as follows:

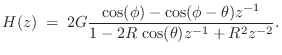

Expressing the pole ![]() in polar form as

in polar form as

![]() ,

and the residue as

,

and the residue as

![]() ,

the last expression above can be rewritten as

,

the last expression above can be rewritten as

Expanding a transfer function into a sum of second-order terms with

real coefficients gives us the filter coefficients for a parallel bank

of real second-order filter sections. (Of course, each real pole can

be implemented in its own real one-pole section in parallel with the

other sections.) In view of the foregoing, we may conclude that every

real filter with ![]() can be implemented as a parallel bank

of biquads.7.6 However, the full generality of a biquad

section (two poles and two zeros) is not needed because the PFE

requires only one zero per second-order term.

can be implemented as a parallel bank

of biquads.7.6 However, the full generality of a biquad

section (two poles and two zeros) is not needed because the PFE

requires only one zero per second-order term.

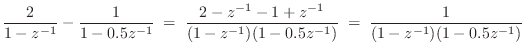

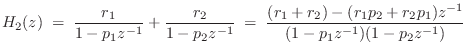

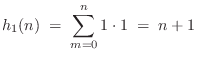

To see why we must stipulate ![]() in Eq.

in Eq.![]() (6.7), consider the sum of two

first-order terms by direct calculation:

(6.7), consider the sum of two

first-order terms by direct calculation:

|

(7.9) |

Notice that the numerator order, viewed as a polynomial in

Inverting the Z Transform

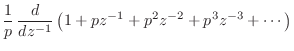

The partial fraction expansion (PFE) provides a simple means for inverting the z transform of rational transfer functions. The PFE provides a sum of first-order terms of the form

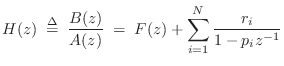

In the improper case, discussed in the next section, we additionally obtain an FIR part in the z transform to be inverted:

The case of repeated poles is addressed in §6.8.5 below.

FIR Part of a PFE

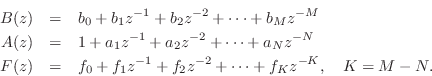

When ![]() in Eq.

in Eq.![]() (6.7), we may perform a step of long division

of

(6.7), we may perform a step of long division

of ![]() to produce an FIR part in parallel with a

strictly proper IIR part:

to produce an FIR part in parallel with a

strictly proper IIR part:

where

When ![]() , we define

, we define ![]() . This type of decomposition is

computed by the residuez function (a matlab function for

computing a complete partial fraction expansion, as illustrated in

§6.8.8 below).

. This type of decomposition is

computed by the residuez function (a matlab function for

computing a complete partial fraction expansion, as illustrated in

§6.8.8 below).

An alternate FIR part is obtained by performing long division on the reversed polynomial coefficients to obtain

where

We may compare these two PFE alternatives as follows:

Let ![]() denote

denote ![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() .

(I.e., we use a subscript to indicate polynomial order, and `

.

(I.e., we use a subscript to indicate polynomial order, and `![]() ' is

omitted for notational simplicity.) Then for

' is

omitted for notational simplicity.) Then for

![]() we have two cases:

we have two cases:

In the first form, the

![]() coefficients are ``left

justified'' in the reconstructed numerator, while in the second form

they are ``right justified''. The second form is generally more

efficient for modeling purposes, since the numerator of the IIR

part (

coefficients are ``left

justified'' in the reconstructed numerator, while in the second form

they are ``right justified''. The second form is generally more

efficient for modeling purposes, since the numerator of the IIR

part (

![]() ) can be used to match additional

terms in the impulse response after the FIR part

) can be used to match additional

terms in the impulse response after the FIR part ![]() has

``died out''.

has

``died out''.

In summary, an arbitrary digital filter transfer function ![]() with

with

![]() distinct poles can always be expressed as a parallel combination

of complex one-pole filters, together with a parallel FIR part

when

distinct poles can always be expressed as a parallel combination

of complex one-pole filters, together with a parallel FIR part

when ![]() . When there is an FIR part, the strictly proper IIR

part may be delayed such that its impulse response begins where that

of the FIR part leaves off.

. When there is an FIR part, the strictly proper IIR

part may be delayed such that its impulse response begins where that

of the FIR part leaves off.

In artificial reverberation applications, the FIR part may correspond to the early reflections, while the IIR part provides the late reverb, which is typically dense, smooth, and exponentially decaying [86]. The predelay (``pre-delay'') control in some commercial reverberators is the amount of pure delay at the beginning of the reverberator's impulse response. Thus, neglecting the early reflections, the order of the FIR part can be viewed as the amount of predelay for the IIR part.

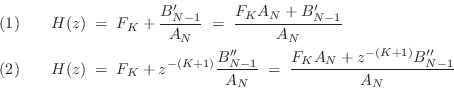

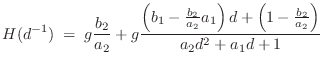

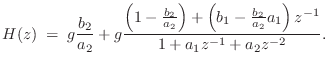

Example: The General Biquad PFE

The general second-order case with ![]() (the so-called

biquad section) can be written when

(the so-called

biquad section) can be written when ![]() as

as

yielding

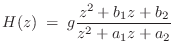

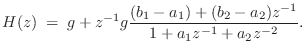

The delayed form of the partial fraction expansion is obtained by

leaving the coefficients in their original order. This corresponds

to writing ![]() as a ratio of polynomials in

as a ratio of polynomials in ![]() :

:

giving

Numerical examples of partial fraction expansions are given in §6.8.8

below. Another worked example, in which the filter

![]() is converted to a set of parallel, second-order

sections is given in §3.12. See also §9.2 regarding

conversion to second-order sections in general, and §G.9.1 (especially

Eq.

is converted to a set of parallel, second-order

sections is given in §3.12. See also §9.2 regarding

conversion to second-order sections in general, and §G.9.1 (especially

Eq.![]() (G.22)) regarding

a state-space approach to partial fraction expansion.

(G.22)) regarding

a state-space approach to partial fraction expansion.

Alternate PFE Methods

Another method for finding the pole residues is to write down the general

form of the PFE, obtain a common denominator, expand the numerator

terms to obtain a single polynomial, and equate like powers of ![]() .

This gives a linear system of

.

This gives a linear system of ![]() equations in

equations in ![]() unknowns

unknowns ![]() ,

,

![]() .

.

Yet another method for finding residues is by means of Taylor series

expansions of the numerator ![]() and denominator

and denominator ![]() about each

pole

about each

pole ![]() , using l'Hôpital's

rule..

, using l'Hôpital's

rule..

Finally, one can alternatively construct a state space realization of a strictly proper transfer function (using, e.g., tf2ss in matlab) and then diagonalize it via a similarity transformation. (See Appendix G for an introduction to state-space models and diagonalizing them via similarity transformations.) The transfer function of the diagonalized state-space model is trivially obtained as a sum of one-pole terms--i.e., the PFE. In other words, diagonalizing a state-space filter realization implicitly performs a partial fraction expansion of the filter's transfer function. When the poles are distinct, the state-space model can be diagonalized; when there are repeated poles, it can be block-diagonalized instead, as discussed further in §G.10.

Repeated Poles

When poles are repeated, an interesting new phenomenon emerges. To see what's going on, let's consider two identical poles arranged in parallel and in series. In the parallel case, we have

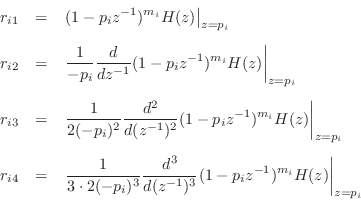

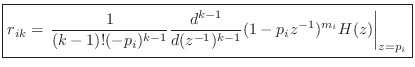

Dealing with Repeated Poles Analytically

A pole of multiplicity ![]() has

has

![]() residues associated with it. For example,

residues associated with it. For example,

and the three residues associated with the pole

Let ![]() denote the

denote the ![]() th residue associated with the pole

th residue associated with the pole ![]() ,

,

![]() .

Successively differentiating

.

Successively differentiating

![]()

![]() times with

respect to

times with

respect to ![]() and setting

and setting ![]() isolates the residue

isolates the residue ![]() :

:

or

Example

For the example of Eq.![]() (6.12), we obtain

(6.12), we obtain

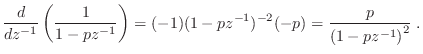

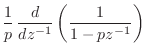

Impulse Response of Repeated Poles

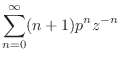

In the time domain, repeated poles give rise to polynomial amplitude envelopes on the decaying exponentials corresponding to the (stable) poles. For example, in the case of a single pole repeated twice, we have

Proof:

First note that

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| (7.13) |

Note that

So What's Up with Repeated Poles?

In the previous section, we found that repeated poles give rise to polynomial amplitude-envelopes multiplying the exponential decay due to the pole. On the other hand, two different poles can only yield a convolution (or sum) of two different exponential decays, with no polynomial envelope allowed. This is true no matter how closely the poles come together; the polynomial envelope can occur only when the poles merge exactly. This might violate one's intuitive expectation of a continuous change when passing from two closely spaced poles to a repeated pole.

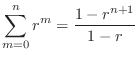

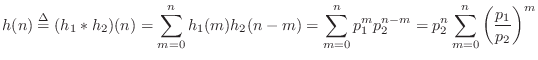

To study this phenomenon further, consider the convolution of two

one-pole impulse-responses

![]() and

and

![]() :

:

The finite limits on the summation result from the fact that both

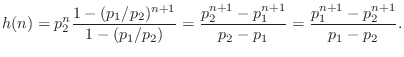

Going back to Eq.![]() (6.14), we have

(6.14), we have

|

(7.15) |

Setting

| (7.16) |

which is the first-order polynomial amplitude-envelope case for a repeated pole. We can see that the transition from ``two convolved exponentials'' to ``single exponential with a polynomial amplitude envelope'' is perfectly continuous, as we would expect.

We also see that the polynomial amplitude-envelopes fundamentally

arise from iterated convolutions. This corresponds to the

repeated poles being arranged in series, rather than in

parallel. The simplest case is when the repeated pole is at ![]() , in

which case its impulse response is a constant:

, in

which case its impulse response is a constant:

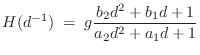

Alternate Stability Criterion

In §5.6 (page ![]() ), a filter was defined to

be stable if its impulse response

), a filter was defined to

be stable if its impulse response ![]() decays to 0 in

magnitude as time

decays to 0 in

magnitude as time ![]() goes to infinity. In §6.8.5, we saw that

the impulse response of every finite-order LTI filter can be expressed

as a possible FIR part (which is always stable) plus a linear

combination of terms of the form

goes to infinity. In §6.8.5, we saw that

the impulse response of every finite-order LTI filter can be expressed

as a possible FIR part (which is always stable) plus a linear

combination of terms of the form

![]() , where

, where ![]() is some

finite-order polynomial in

is some

finite-order polynomial in ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the

is the ![]() th pole of the

filter. In this form, it is clear that the impulse response always

decays to zero when each pole is strictly inside the unit circle of

the

th pole of the

filter. In this form, it is clear that the impulse response always

decays to zero when each pole is strictly inside the unit circle of

the ![]() plane, i.e., when

plane, i.e., when ![]() . Thus, having all poles strictly

inside the unit circle is a sufficient criterion for filter

stability. If the filter is observable (meaning that there are

no pole-zero cancellations in the transfer function from input to

output), then this is also a necessary criterion.

. Thus, having all poles strictly

inside the unit circle is a sufficient criterion for filter

stability. If the filter is observable (meaning that there are

no pole-zero cancellations in the transfer function from input to

output), then this is also a necessary criterion.

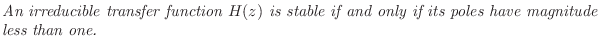

A transfer function with no pole-zero cancellations is said to be

irreducible. For example,

![]() is

irreducible, while

is

irreducible, while

![]() is reducible, since

there is the common factor of

is reducible, since

there is the common factor of

![]() in the numerator and

denominator. Using this terminology, we may state the following

stability criterion:

in the numerator and

denominator. Using this terminology, we may state the following

stability criterion:

This characterization of stability is pursued further in §8.4, and yet another stability test (most often used in practice) is given in §8.4.1.

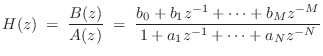

Summary of the Partial Fraction Expansion

In summary, the partial fraction expansion can be used to expand any rational z transform

|

(7.17) |

for

for

- When

, perform a step of long division to obtain

an FIR part

, perform a step of long division to obtain

an FIR part  and a strictly proper IIR part

and a strictly proper IIR part

.

.

- Find the

poles

poles  ,

,

(roots of

(roots of  ).

).

- If the poles are distinct, find the

residues

residues  ,

,

from

from

- If there are repeated poles, find the additional residues via

the method of §6.8.5, and the general form of the PFE is

where denotes the number of distinct poles, and

denotes the number of distinct poles, and

denotes the multiplicity of the

denotes the multiplicity of the  th pole.

th pole.

In step 2, the poles are typically found by factoring the

denominator polynomial ![]() . This is a dangerous step numerically

which may fail when there are many poles, especially when many poles

are clustered close together in the

. This is a dangerous step numerically

which may fail when there are many poles, especially when many poles

are clustered close together in the ![]() plane.

plane.

The following matlab code illustrates factoring

![]() to

obtain the three roots,

to

obtain the three roots,

![]() ,

, ![]() :

:

A = [1 0 0 -1]; % Filter denominator polynomial poles = roots(A) % Filter poles

See Chapter 9 for additional discussion regarding digital filters implemented as parallel sections (especially §9.2.2).

Software for Partial Fraction Expansion

Figure 6.3 illustrates the use of residuez (§J.5) for performing a partial fraction expansion on the transfer function

B = [1 0 0 0.125]; A = [1 0 0 0 0 0.9^5]; [r,p,f] = residuez(B,A) % r = % 0.16571 % 0.22774 - 0.02016i % 0.22774 + 0.02016i % 0.18940 + 0.03262i % 0.18940 - 0.03262i % % p = % -0.90000 % -0.27812 - 0.85595i % -0.27812 + 0.85595i % 0.72812 - 0.52901i % 0.72812 + 0.52901i % % f = [](0x0) |

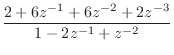

Example 2

For the filter

we obtain the output of residued (§J.6) shown in Fig.6.4. In contrast to residuez, residued delays the IIR part until after the FIR part. In contrast to this result, residuez returns r=[-24;16] and f=[10;2], corresponding to the PFE

| (7.22) |

in which the FIR and IIR parts have overlapping impulse responses.

See Sections J.5 and J.6 starting on page ![]() for

listings of residuez, residued and related

discussion.

for

listings of residuez, residued and related

discussion.

B=[2 6 6 2]; A=[1 -2 1]; [r,p,f,m] = residued(B,A) % r = % 8 % 16 % % p = % 1 % 1 % % f = % 2 10 % % m = % 1 % 2 |

Polynomial Multiplication in Matlab

The matlab function conv (convolution) can be used to perform polynomial multiplication. For example:

B1 = [1 1]; % 1st row of Pascal's triangle B2 = [1 2 1]; % 2nd row of Pascal's triangle B3 = conv(B1,B2) % 3rd row % B3 = 1 3 3 1 B4 = conv(B1,B3) % 4th row % B4 = 1 4 6 4 1 % ...The matlab conv(B1,B2) is identical to filter(B1,1,B2), except that conv returns the complete convolution of its two input vectors, while filter truncates the result to the length of the ``input signal'' B2.7.10 Thus, if B2 is zero-padded with length(B1)-1 zeros, it will return the complete convolution:

B1 = [1 2 3]; B2 = [4 5 6 7]; conv(B1,B2) % ans = 4 13 28 34 32 21 filter(B1,1,B2) % ans = 4 13 28 34 filter(B1,1,[B2,zeros(1,length(B1)-1)]) % ans = 4 13 28 34 32 21

Polynomial Division in Matlab

The matlab function deconv (deconvolution) can be used to perform polynomial long division in order to split an improper transfer function into its FIR and strictly proper parts:

B = [ 2 6 6 2]; % 2*(1+1/z)^3 A = [ 1 -2 1]; % (1-1/z)^2 [firpart,remainder] = deconv(B,A) % firpart = % 2 10 % remainder = % 0 0 24 -8Thus, this example finds that

Bh = remainder + conv(firpart,A) % = 2 6 6 2

The operation deconv(B,A) can be implemented using filter in a manner analogous to the polynomial multiplication case (see §6.8.8 above):

firpart = filter(B,A,[1,zeros(1,length(B)-length(A))]) % = 2 10 remainder = B - conv(firpart,A) % = 0 0 24 -8That this must work can be seen by looking at Eq.

In summary, we may conveniently use convolution and deconvolution to perform polynomial multiplication and division, respectively, such as when converting transfer functions to various alternate forms.

When carrying out a partial fraction expansion on a transfer function having a numerator order which equals or exceeds the denominator order, a necessary preliminary step is to perform long division to obtain an FIR filter in parallel with a strictly proper transfer function. This section describes how an FIR part of any length can be extracted from an IIR filter, and this can be used for PFEs as well as for more advanced applications [].

Next Section:

Problems

Previous Section:

Series and Parallel Transfer Functions

![$\displaystyle (2+10z^{-1}) + z^{-2}\left[\frac{8}{1-z^{-1}} + \frac{16}{(1-z^{-1})^2}\right]

\protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img819.png)