Time-Varying Two-Pole Filters

It is quite common to want to vary the resonance frequency of a resonator in real time. This is a special case of a tunable filter. In the pre-digital days of analog synthesizers, filter modules were tuned by means of control voltages, and were thus called voltage-controlled filters (VCF). In the digital domain, control voltages are replaced by time-varying filter coefficients. In the time-varying case, the choice of filter structure has a profound effect on how the filter characteristics vary with respect to coefficient variations. In this section, we will take a look at the time-varying two-pole resonator.

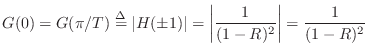

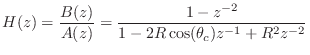

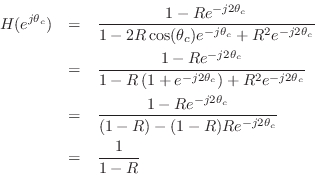

Evaluating the transfer function of the two-pole resonator

(Eq.![]() (B.1)) at the point

(B.1)) at the point

![]() on the unit circle

(the filter's resonance frequency

on the unit circle

(the filter's resonance frequency

![]() ) yields a gain at resonance equal to

) yields a gain at resonance equal to

For simplicity, let

Since

An important fact we can now see is that the gain at resonance depends markedly on the resonance frequency. In particular, the ratio of the two cases just analyzed is

Note that the ratio of the dc resonance gain to the ![]() resonance

gain is unbounded! The sharper the resonance (the closer

resonance

gain is unbounded! The sharper the resonance (the closer ![]() is to 1), the greater the disparity in the gain.

is to 1), the greater the disparity in the gain.

Figure B.17 illustrates a number of resonator frequency responses

for the case ![]() . (Resonators in practice may use values of

. (Resonators in practice may use values of ![]() even closer to 1 than this--even the case

even closer to 1 than this--even the case ![]() is used for making

recursive digital sinusoidal oscillators [90].) For

resonator tunings at dc and

is used for making

recursive digital sinusoidal oscillators [90].) For

resonator tunings at dc and ![]() , we predict the resonance gain to

be

, we predict the resonance gain to

be

![]() dB, and this is what we see in the plot.

When the resonance is tuned to

dB, and this is what we see in the plot.

When the resonance is tuned to ![]() , the gain drops well below 40

dB. Clearly, we will need to compensate this gain variation when

trying to use the two-pole digital resonator as a tunable filter.

, the gain drops well below 40

dB. Clearly, we will need to compensate this gain variation when

trying to use the two-pole digital resonator as a tunable filter.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/resgain}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1506.png) |

Figure B.18 shows the same type of plot for the complex

one-pole resonator

![]() , for

, for ![]() and

10 values of

and

10 values of ![]() . In this case, we expect the frequency

response evaluated at the center frequency to be

. In this case, we expect the frequency

response evaluated at the center frequency to be

![]() . Thus, the gain at

resonance for the plotted example is

. Thus, the gain at

resonance for the plotted example is

![]() db for all

tunings. Furthermore, for the complex resonator, the resonance gain

is also exactly equal to the peak gain.

db for all

tunings. Furthermore, for the complex resonator, the resonance gain

is also exactly equal to the peak gain.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cresgain}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1509.png) |

Normalizing Two-Pole Filter Gain at Resonance

The question we now pose is how to best compensate the tunable

two-pole resonator of §B.1.3 so that its peak gain is the same for

all tunings. Looking at Fig.B.17, and remembering the graphical

method for determining the amplitude response,B.6 it is intuitively

clear that we can help matters by adding two zeros to the

filter, one near dc and the other near ![]() . A zero exactly at dc

is provided by the term

. A zero exactly at dc

is provided by the term

![]() in the transfer function numerator.

Similarly, a zero at half the sampling rate is provided by the term

in the transfer function numerator.

Similarly, a zero at half the sampling rate is provided by the term

![]() in the numerator. The series combination of both zeros

gives the numerator

in the numerator. The series combination of both zeros

gives the numerator

![]() . The complete

second-order transfer function then becomes

. The complete

second-order transfer function then becomes

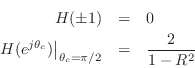

Checking the gain for the case

which is better behaved, but now the response falls to zero at dc and

![]() rather than being heavily boosted, as we found in

Eq.

rather than being heavily boosted, as we found in

Eq.![]() (B.12).

(B.12).

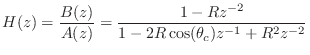

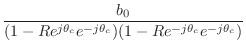

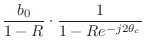

Constant Resonance Gain

It turns out it is possible to normalize exactly the

resonance gain of the second-order resonator tuned by a

single coefficient [89]. This is accomplished by

placing the two zeros at

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the radius of

the complex-conjugate pole pair . The transfer function numerator

becomes

is the radius of

the complex-conjugate pole pair . The transfer function numerator

becomes

![]() , yielding

the total transfer function

, yielding

the total transfer function

Thus, the gain at resonance is ![]() for all resonance tunings

for all resonance tunings ![]() .

.

Figure B.19 shows a family of amplitude responses for the

constant resonance-gain two-pole, for various values of ![]() and

and

![]() . We see an excellent improvement in the regularity of the

amplitude response as a function of tuning.

. We see an excellent improvement in the regularity of the

amplitude response as a function of tuning.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cgresgain}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1523.png) |

Peak Gain Versus Resonance Gain

While the constant resonance-gain filter is very well behaved, it is

not ideal, because, while the resonance gain is perfectly

normalized, the peak gain is not. The amplitude-response peak

does not occur exactly at the resonance frequencies

![]() except for the special cases

except for the special cases

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() . At other resonance frequencies, the peak due to one pole

is shifted by the presence of the other pole.

When

. At other resonance frequencies, the peak due to one pole

is shifted by the presence of the other pole.

When ![]() is close to 1, the shifting can be negligible, but in more

damped resonators, e.g., when

is close to 1, the shifting can be negligible, but in more

damped resonators, e.g., when ![]() , there can be a significant

difference between the gain at resonance and the true peak gain.

, there can be a significant

difference between the gain at resonance and the true peak gain.

Figure B.20 shows a family of amplitude responses for the

constant resonance-gain two-pole, for various values of ![]() and

and

![]() . We see that while the gain at resonance is exactly the same

in all cases, the actual peak gain varies somewhat, especially

near dc and

. We see that while the gain at resonance is exactly the same

in all cases, the actual peak gain varies somewhat, especially

near dc and ![]() when the two poles come closest together. A more

pronounced variation in peak gain can be seen in

Fig.B.21, for which the pole radii have been reduced

to

when the two poles come closest together. A more

pronounced variation in peak gain can be seen in

Fig.B.21, for which the pole radii have been reduced

to ![]() .

.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cgresgaindamped}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1526.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cgresgaindampedp5}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1527.png) |

Constant Peak-Gain Resonator

It is surprisingly easy to normalize exactly the peak gain in a second-order resonator tuned by a single coefficient [94]. The filter structure that accomplishes this is the one we already considered in §B.6.1:

That is, the two-pole resonator normalized by zeros at

Real-time audio ``plugins'' based on the constant-peak-gain resonator are developed in Appendix K.

The peak gain is ![]() , so multiplying the transfer function by

, so multiplying the transfer function by

![]() normalizes the peak gain to one for all tunings. It can

also be shown [94] that the peak gain coincides with the

variance gain when the resonator is driven by white noise. That

is, if the variance of the driving noise is

normalizes the peak gain to one for all tunings. It can

also be shown [94] that the peak gain coincides with the

variance gain when the resonator is driven by white noise. That

is, if the variance of the driving noise is ![]() , the variance

of the noise at the resonator output is

, the variance

of the noise at the resonator output is

![]() .

Therefore, scaling the resonator input by

.

Therefore, scaling the resonator input by

![]() will

normalize the resonator such that the output signal power equals the

input signal power when the input signal is white noise.

will

normalize the resonator such that the output signal power equals the

input signal power when the input signal is white noise.

Frequency response overlays for the constant-peak-gain resonator are

shown in Fig.B.23 (![]() ), Fig.B.20

(

), Fig.B.20

(![]() ), and Fig.B.21 (

), and Fig.B.21 (![]() ). While the peak

frequency may be far from the resonance tuning in the more heavily

damped examples, the peak gain is always normalized to unity. The

normalized radian frequency

). While the peak

frequency may be far from the resonance tuning in the more heavily

damped examples, the peak gain is always normalized to unity. The

normalized radian frequency

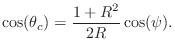

![]() at which the peak gain

occurs is related to the pole angle

at which the peak gain

occurs is related to the pole angle

![]() by

[94]

by

[94]

When the right-hand side of the above equation exceeds 1 in magnitude, there is no (real) solution for the pole frequency

Thus, ![]() must be close to 1 to obtain a resonant peak near dc (a case

commonly needed in audio work) or half the sampling rate (rarely

needed in practice). When

must be close to 1 to obtain a resonant peak near dc (a case

commonly needed in audio work) or half the sampling rate (rarely

needed in practice). When ![]() is much less than 1, the peak frequency

is much less than 1, the peak frequency

![]() cannot leave a small interval near one-fourth the sampling

rate, as can be seen at the far left in Fig.B.22.

cannot leave a small interval near one-fourth the sampling

rate, as can be seen at the far left in Fig.B.22.

Figure B.22 predicts that for ![]() , the lowest peak-gain

frequency should be around

, the lowest peak-gain

frequency should be around

![]() radian per sample.

Figure B.21 agrees with this prediction.

radian per sample.

Figure B.21 agrees with this prediction.

As Figures B.23 through B.25 show, the peak gain remains

constant even at very low and very high frequencies, to the extent

they are reachable for a given ![]() . The zeros at dc and

. The zeros at dc and ![]() preclude the possibility of peaks at exactly those frequencies, but

for

preclude the possibility of peaks at exactly those frequencies, but

for ![]() near 1, we can get very close to having a peak at dc or

near 1, we can get very close to having a peak at dc or

![]() , as shown in Figures B.19 and B.20.

, as shown in Figures B.19 and B.20.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cpgresgain}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1546.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cpgresgaindamped}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1547.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/cpgresgaindampedp5}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1548.png) |

Four-Pole Tunable Lowpass/Bandpass Filters

As a practical note, it is worth mentioning that in popular analog synthesizers (both real and virtualB.7), VCFs are typically fourth order rather than second order as we have studied here. Perhaps the best known VCF is the Moog VCF. The four-pole Moog VCF is configured to be a lowpass filter with an optional resonance near the cut-off frequency. When the resonance is strong, it functions more like a resonator than a lowpass filter. Various methods for digitizing the Moog VCF are described in [95]. It turns out to be nontrivial to preserve all desirable properties of the analog filter (such as frequency response, order, and control structure), when translated to digital form by standard means.

Next Section:

Elementary Filter Problems

Previous Section:

Peaking Equalizers

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/psivsthetac}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/filters/img1543.png)