Acoustic Wave Propagation Simulation

Delay lines can be used to simulate acoustic wave propagation. We start with the simplest case of a pure traveling wave, followed by the more general case of spherical waves. We then look at the details of a simple acoustic echo simulation using a delay line to model the difference in time-of-arrival between the direct and reflected signals.

Traveling Waves

In acoustic wave propagation, pure delays can be used to simulate traveling waves. A traveling wave is any kind of wave which propagates in a single direction with negligible change in shape. An important class of traveling waves is ``plane waves'' in air which create ``standing waves'' in rectangular enclosures such as ``shoebox'' shaped concert halls. Also, far away from any acoustic source (where ``far'' is defined as ``many wavelengths''), the direct sound emanating from any source can be well approximated as a plane wave, and thus as a traveling wave.

Another case in which plane waves dominate is the cylindrical bore, such as the bore of a clarinet or the straight tube segments of a trumpet. Additionally, the vocal tract is generally simulated using plane waves, though in this instance there is a higher degree of approximation error.

Transverse and longitudinal waves in a vibrating string, such as on a guitar, are also nearly perfect traveling waves, and they can be simulated to a very high degree of perceptual accuracy by approximating them as ideal, while implementing slight losses and dispersion once per period (i.e., at one particular point along the ``virtual string'').

In a conical bore, we find sections of spherical waves taking

the place of plane waves. However, they still ``travel'' like plane

waves, and we can still use a delay line to simulate their

propagation. The same applies to spherical waves created by a ``point

source.'' Spherical waves will be considered on

page ![]() .

.

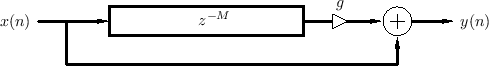

Damped Traveling Waves

The delay line shown in Fig.2.1 on page ![]() can be used

to simulate any traveling wave, where the traveling wave must

propagate in one direction with a fixed waveshape. If a traveling

wave attenuates as it propagates, with the same attenuation

factor at each frequency, the attenuation can be simulated by a simple

scaling of the delay line output (or input), as shown in

Fig.2.3. This is perhaps the simplest example of

the important principle of lumping distributed losses at

discrete points. That is, it is not necessary to implement a small

attenuation

can be used

to simulate any traveling wave, where the traveling wave must

propagate in one direction with a fixed waveshape. If a traveling

wave attenuates as it propagates, with the same attenuation

factor at each frequency, the attenuation can be simulated by a simple

scaling of the delay line output (or input), as shown in

Fig.2.3. This is perhaps the simplest example of

the important principle of lumping distributed losses at

discrete points. That is, it is not necessary to implement a small

attenuation ![]() for each time-step of wave propagation; the same

result is obtained at the delay-line output if propagation is

``lossless'' within the delay line, and the total cumulative

attenuation

for each time-step of wave propagation; the same

result is obtained at the delay-line output if propagation is

``lossless'' within the delay line, and the total cumulative

attenuation ![]() is applied at the output. The input-output

simulation is exact, while the signal samples inside the delay line

are simulated with a slight gain error. If the internal signals are

needed later, they can be tapped out using correcting gains. For

example, the signal half way along the delay line can be tapped using

a coefficient of

is applied at the output. The input-output

simulation is exact, while the signal samples inside the delay line

are simulated with a slight gain error. If the internal signals are

needed later, they can be tapped out using correcting gains. For

example, the signal half way along the delay line can be tapped using

a coefficient of ![]() in order to make it an exact second output.

In summary, computational efficiency can often be greatly increased at

no cost to accuracy by lumping losses only at the outputs and points

of interaction with other simulations.

in order to make it an exact second output.

In summary, computational efficiency can often be greatly increased at

no cost to accuracy by lumping losses only at the outputs and points

of interaction with other simulations.

Modeling traveling-wave attenuation by a scale factor is only exact

physically when all frequency components decay at the same rate. For

accurate acoustic modeling, it is usually necessary to replace the

constant scale factor ![]() by a digital filter

by a digital filter ![]() which

implements frequency-dependent attenuation, as depicted in

Fig.2.4. In principle, a linear time-invariant (LTI) filter

can provide an independent attenuation factor at each frequency.

Section 2.3 addresses this case in more detail.

Frequency-dependent damping substitution will be used in artificial

reverberation design in §3.7.4.

which

implements frequency-dependent attenuation, as depicted in

Fig.2.4. In principle, a linear time-invariant (LTI) filter

can provide an independent attenuation factor at each frequency.

Section 2.3 addresses this case in more detail.

Frequency-dependent damping substitution will be used in artificial

reverberation design in §3.7.4.

Dispersive Traveling Waves

In many acoustic systems, such as piano strings

(§9.4.1,§C.6), wave propagation is also

significantly dispersive. A wave-propagation medium is said to

be dispersive if the speed of wave propagation is not the same at all

frequencies. As a result, a propagating wave shape will ``disperse''

(change shape) as its various frequency components travel at different

speeds. Dispersive propagation in one direction can be simulated

using a delay line in series with a nonlinear phase filter, as

indicated in Fig.2.5. If there is no damping, the filter

![]() must be all-pass [449], i.e.,

must be all-pass [449], i.e.,

![]() for

all

for

all

![]() .

.

Converting Propagation Distance to Delay Length

We may regard the delay-line memory itself as the fixed ``air'' which

propagates sound samples at a fixed speed ![]() (

(![]() meters per

second at

meters per

second at ![]() degrees Celsius and 1 atmosphere). The input signal

degrees Celsius and 1 atmosphere). The input signal

![]() can be associated with a sound source, and the output signal

can be associated with a sound source, and the output signal

![]() (see Fig.2.1 on page

(see Fig.2.1 on page ![]() ) can be associated with

the listening point. If the listening point is

) can be associated with

the listening point. If the listening point is ![]() meters away from

the source, then the delay line length

meters away from

the source, then the delay line length ![]() needs to be

needs to be

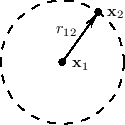

Spherical Waves from a Point Source

Acoustic theory tells us that a point source produces a spherical wave in an ideal isotropic (uniform) medium such as air. Furthermore, the sound from any radiating surface can be computed as the sum of spherical wave contributions from each point on the surface (including any relevant reflections). The Huygens-Fresnel principle explains wave propagation itself as the superposition of spherical waves generated at each point along a wavefront (see, e.g., [349, p. 175]). Thus, all linear acoustic wave propagation can be seen as a superposition of spherical traveling waves.

To a good first approximation, wave energy is conserved as it

propagates through the air. In a spherical pressure wave of radius

![]() , the energy of the wavefront is spread out over the spherical

surface area

, the energy of the wavefront is spread out over the spherical

surface area ![]() . Therefore, the energy per unit area of an

expanding spherical pressure wave decreases as

. Therefore, the energy per unit area of an

expanding spherical pressure wave decreases as ![]() . This is

called spherical spreading loss. It is also an example of an

inverse square law which is found repeatedly in the physics of

conserved quantities in three-dimensional space. Since energy is

proportional to amplitude squared, an inverse square law for energy

translates to a

. This is

called spherical spreading loss. It is also an example of an

inverse square law which is found repeatedly in the physics of

conserved quantities in three-dimensional space. Since energy is

proportional to amplitude squared, an inverse square law for energy

translates to a ![]() decay law for amplitude.

decay law for amplitude.

The sound-pressure amplitude of a traveling wave is proportional to

the square-root of its energy per unit area. Therefore, in a

spherical traveling wave, acoustic amplitude is proportional to ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the radius of the sphere. In terms of Cartesian

coordinates, the amplitude

is the radius of the sphere. In terms of Cartesian

coordinates, the amplitude

![]() at the point

at the point

![]() due to a point source located at

due to a point source located at

![]() is given by

is given by

In summary, every point of a radiating sound source emits spherical

traveling waves in all directions which decay as ![]() , where

, where ![]() is

the distance from the source. The amplitude-decay by

is

the distance from the source. The amplitude-decay by ![]() can be

considered a consequence of energy conservation for propagating waves.

(The energy spreads out over the surface of an expanding sphere.) We

often visualize such waves as ``rays'' emanating from the source, and

we can simulate them as a delay line along with a

can be

considered a consequence of energy conservation for propagating waves.

(The energy spreads out over the surface of an expanding sphere.) We

often visualize such waves as ``rays'' emanating from the source, and

we can simulate them as a delay line along with a ![]() scaling

coefficient (see Fig.2.7). In contrast, since

plane waves propagate with no decay at all, each ``ray'' can be

considered lossless, and the simulation involves only a delay line

with no scale factor, as shown in Fig.2.1 on page

scaling

coefficient (see Fig.2.7). In contrast, since

plane waves propagate with no decay at all, each ``ray'' can be

considered lossless, and the simulation involves only a delay line

with no scale factor, as shown in Fig.2.1 on page ![]() .

.

Reflection of Spherical or Plane Waves

When a spreading spherical wave reaches a wall or other obstacle, it is either reflected or scattered. A wavefront is reflected when it impinges on a surface which is flat over at least a few wavelengths in each direction.3.1 Reflected wavefronts can be easily mapped using ray tracing, i.e., the reflected ray leaves at an angle to the surface equal to the angle of incidence (``law of reflection''). Wavefront reflection is also called specular reflection, especially when considering light waves.

A wave is scattered when it encounters a surface which has variations on the scale of the spatial wavelength. A scattering reflection is also called a diffuse reflection. As a special case, objects smaller than a wavelength yield a diffuse reflection which approaches a spherical wave as the object approaches zero volume. More generally, each point of a scatterer can be seen as emitting a new spherically spreading wavefront in response to the incoming wave--a decomposition known as Huygen's principle, as mentioned in the previous section. The same process happens in reflection, but the hemispheres emitted by each point of the flat reflecting surface combine to form a more organized wavefront which is the same as the incident wave but traveling in a new direction.

The distinction between specular and diffuse reflections is dependent

on frequency. Since sound travels approximately 1 foot per

millisecond, a cube 1 foot on each side will ``specularly reflect''

directed ``beams'' of sound energy above ![]() KHz, and will ``diffuse''

or scatter sound energy below

KHz, and will ``diffuse''

or scatter sound energy below ![]() KHz. A good concert hall, for

example, will have plenty of diffusion. As a general rule,

reverberation should be diffuse in order to avoid ``standing waves''

(isolated energetic modes). In other words, in reverberation, we wish

to spread the sound energy uniformly in both time and space, and we do

not want any specific spatial or temporal patterns in the

reverberation.

KHz. A good concert hall, for

example, will have plenty of diffusion. As a general rule,

reverberation should be diffuse in order to avoid ``standing waves''

(isolated energetic modes). In other words, in reverberation, we wish

to spread the sound energy uniformly in both time and space, and we do

not want any specific spatial or temporal patterns in the

reverberation.

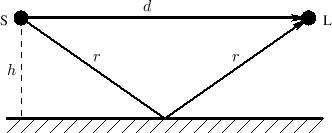

An Acoustic Echo Simulator

An acoustic echo is one of the simplest acoustic modeling problems. Echoes occur when a sound arrives via more than one acoustic propagation path, as shown in Fig.2.8. We may hear a discrete echo, for example, if we clap our hands standing in front of a large flat wall outdoors, such as the side of a building. To be perceived as an echo, however, the reflection must arrive well after the direct signal (or previous echo).

|

A common cause of echoes is ``multipath'' wave propagation, as

diagrammed in Fig.2.8. The acoustic source is denoted by `S',

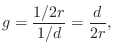

the listener by `L', and they are at the same height ![]() meters

from a reflecting surface. The direct path is

meters

from a reflecting surface. The direct path is ![]() meters long, while

the length of the single reflection is

meters long, while

the length of the single reflection is ![]() meters. These quantities

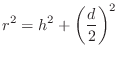

are of course related by the Pythagorean theorem:

meters. These quantities

are of course related by the Pythagorean theorem:

Figure 2.9 illustrates an echo simulator for the case of a direct signal and single echo, as shown in Fig.2.8. It is common practice to pull out and discard any common delay which affects all signals equally, since such a delay does not affect timbre; thus, the direct signal delay is not implemented at all in Fig.2.9. Similarly, it is not necessary to implement the attenuation of the direct signal due to propagation, since it is the relative amplitude of the direct signal and its echoes which affect timbre.

From the geometry in Fig.2.8, we see that the delay-line length in Fig.2.9 should be

Program for Acoustic Echo Simulation

The following main program (Fig.2.10) simulates a simple acoustic echo using the delayline function in Fig.2.2. It reads a sound file and writes a sound file containing a single, discrete echo at the specified delay. For simplicity, utilities from the free Synthesis Tool Kit (STK) (Version 4.2.x) are used for sound input/output [86].3.2

/* Acoustic echo simulator, main C++ program. Compatible with STK version 4.2.1. Usage: main inputsoundfile Writes main.wav as output soundfile */ #include "FileWvIn.h" /* STK soundfile input support */ #include "FileWvOut.h" /* STK soundfile output support */ static const int M = 20000; /* echo delay in samples */ static const int g = 0.8; /* relative gain factor */ #include "delayline.c" /* defined previously */ int main(int argc, char *argv[]) { long i; Stk::setSampleRate(FileRead(argv[1]).fileRate()); FileWvIn input(argv[1]); /* read input soundfile */ FileWvOut output("main"); /* creates main.wav */ long nsamps = input.getSize(); for (i=0;i<nsamps+M;i++) { StkFloat insamp = input.tick(); output.tick(insamp + g * delayline(insamp)); } } |

In summary, a delay line simulates the time delay associated

with wave propagation in a particular direction. Attenuation (e.g.,

by ![]() ) associated with ray propagation can of course be simulated

by multiplying the delay-line output by some constant

) associated with ray propagation can of course be simulated

by multiplying the delay-line output by some constant ![]() .

.

Next Section:

Lossy Acoustic Propagation

Previous Section:

Delay Lines