Wave Digital Elements

When modeling mechanical systems composed of masses, springs, and dashpots, it is best to begin with an electrical equivalent circuit. Equivalent circuits make clear the network-theoretic structure of the system, clearly indicating, for example, whether interacting elements should be connected in series or parallel. Each element of the equivalent circuit can then be replaced by a first-order wave digital element, and the elements are finally parallel or series connected by means of scattering-junction interfaces known as adaptors.

Wave digital elements may be derived from their describing differential equations (in continuous time) as follows:

- First express

all physical quantities (such as force and velocity) in terms of

traveling-wave components. The traveling wave components are called

wave variables. For example, the force

on a mass is

decomposed as

on a mass is

decomposed as

, where

, where

is regarded as a

traveling wave propagating toward the mass, while

is regarded as a

traveling wave propagating toward the mass, while

is

seen as the traveling component propagating

away from the mass. A ``traveling wave'' view of

force mediation is actually much closer to physical reality than any

instantaneous model.

is

seen as the traveling component propagating

away from the mass. A ``traveling wave'' view of

force mediation is actually much closer to physical reality than any

instantaneous model.

- Second, digitize the resulting traveling-wave system using the

bilinear transform. The bilinear transform is equivalent in

the time domain to the

trapezoidal rule for numerical integration (see §7.3.2).

- Connect

elementary units together by means of

elementary units together by means of

-port scattering junctions. There are two basic

types of scattering junction, one for parallel, and one for series

connection. (See §C.8 for the theory of scattering junctions.)

-port scattering junctions. There are two basic

types of scattering junction, one for parallel, and one for series

connection. (See §C.8 for the theory of scattering junctions.)

An important benefit of introducing wave variables prior to bilinear transformation is the elimination of delay-free loops when connecting elementary building blocks. In other words, any number of elementary models can be interconnected, in series or in parallel, and the resulting finite-difference scheme remains explicit (free of delay-free loops).

A Physical Derivation of Wave Digital Elements

This section provides a ``physical'' derivation of Wave Digital Filters (WDF), which contrasts somewhat with the more formal derivation common in the literature. The derivation is presented as a numbered series of steps (some with rather long discussions):

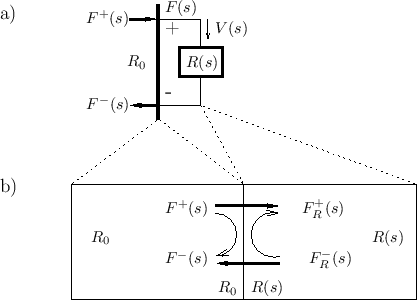

- To each element, such as a capacitor or inductor, attach a

length of waveguide (electrical transmission line) having wave

impedance

, and make it infinitesimally long. (Take the limit as

its length goes to zero.) A schematic depiction of this is shown in

Fig.F.1a. For consistency, all signals are Laplace transforms of

their respective time-domain signals. The length must approach zero

in order not to introduce propagation delays into the signal path.

, and make it infinitesimally long. (Take the limit as

its length goes to zero.) A schematic depiction of this is shown in

Fig.F.1a. For consistency, all signals are Laplace transforms of

their respective time-domain signals. The length must approach zero

in order not to introduce propagation delays into the signal path.

Figure F.1: a) Physical schematic for the derivation of a wave digital model of driving-point impedance  . The inserted

waveguide impedance

. The inserted

waveguide impedance  is real and positive, but otherwise

arbitrary. b) Expanded view of the interior of the infinitesimal

waveguide section, also representing the termination impedance

is real and positive, but otherwise

arbitrary. b) Expanded view of the interior of the infinitesimal

waveguide section, also representing the termination impedance  as an impedance-step within the waveguide.

as an impedance-step within the waveguide.

Points to note:

- The infinitesimal waveguide is terminated by the element.

The element reflects waves as if it were a new waveguide section at

impedance

, as depicted in Fig.F.1b.

, as depicted in Fig.F.1b.

- The interface to the element is recast as traveling-wave

components

and

and  at impedance

at impedance  .

In terms of these components, the physical force on the element is

obtained by adding them together:

.

In terms of these components, the physical force on the element is

obtained by adding them together:

.

.

- The waveguide impedance

is arbitrary because it

has been physically introduced. We will need to know it when we

connect this element to other elements. The element's interface to

other elements is now a waveguide (transmission line) at real

impedance

is arbitrary because it

has been physically introduced. We will need to know it when we

connect this element to other elements. The element's interface to

other elements is now a waveguide (transmission line) at real

impedance  .

.

- The junction is ``parallel'' (cf. §7.2):

- Force (voltage) must be continuous across the junction, since

otherwise there would be a finite force across a zero mass, producing

infinite acceleration.

- The sum of velocities (currents) into the junction must be zero

by conservation of mass (charge).

- Force (voltage) must be continuous across the junction, since

otherwise there would be a finite force across a zero mass, producing

infinite acceleration.

- The infinitesimal waveguide is terminated by the element.

The element reflects waves as if it were a new waveguide section at

impedance

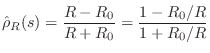

Reflectance of a General Lumped Waveguide Termination

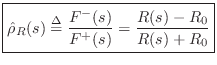

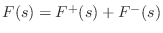

Calculate the reflectance of the terminated waveguide. That is, find the Laplace transform of the return wave divided by the Laplace transform of the input wave going into the waveguide. In general, the reflectance of an impedance step for force waves (voltage waves in the electrical case) is

This is easily derived from continuity constraints across the junction. Specifically, referring to Fig.F.1b, let

By the definition of wave impedance in a waveguide, we have

Thus,

![\begin{eqnarray*}

0 &=& V(s) + V_R(s)\\

&=& \left[V^{+}(s)+V^{-}(s)\right] + ...

...s)}\right]

&=& \frac{2}{R_0}F^{+}(s) + \frac{2}{R(s)}F^{+}_R(s)

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img4758.png)

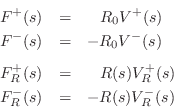

Defining

![]() and

and

![]() , we have

, we have

Now that we've solved for the junction force

Finally, the force-wave reflectance of an impedance step from

as claimed.

Reflectances of Elementary Impedances

We now derive the reflectances of the elements used in LTI analog electric circuits, viz., the capacitor, inductor, and resistor.

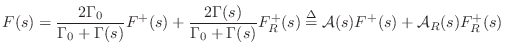

Capacitor Reflectance

For a capacitor of ![]() Farads, the driving-point impedance is (see

§7.1.3)

Farads, the driving-point impedance is (see

§7.1.3)

Inductor Reflectance

For an inductor of ![]() Henrys, we have

Henrys, we have

Resistor Reflectance

Finally, for a resistor of ![]() Ohms, we get

Ohms, we get

Note that both the capacitor and inductor reflectances are

stable allpass filters, as they must be. Also, the resistor

reflectance is always less than 1, no matter what waveguide impedance

![]() we choose.

we choose.

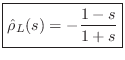

Choosing Impedance to Simplify Element Reflectance

Observe that there is a natural choice for each waveguide impedance which will give us a normalized, ``universal reflectance'' for each element:

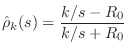

- For the capacitor, setting

gives

gives

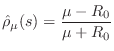

- For the inductor, setting

gives

gives

- And for the resistor, we set

to obtain

to obtain

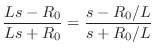

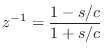

Digitizing Elementary Reflectances by Bilinear Transform

Going to discrete time via the bilinear transform means making the substitution

|

(F.11) |

where

Solving for ![]() gives us the inverse bilinear transform:

gives us the inverse bilinear transform:

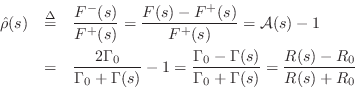

In this case, we see that setting ![]() further simplifies our

universal reflectances in the digital domain:

further simplifies our

universal reflectances in the digital domain:

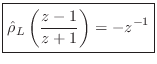

- For the ``wave digital capacitor'' (or spring), Eq.

(F.8) becomes

(F.8) becomes

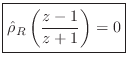

- For the ``wave digital inductor'' (or mass), Eq.

(F.9) becomes

(F.9) becomes

- And for the ``wave digital resistor'' (or dashpot), Eq.

(F.10) becomes

as before in the continuous-time case.

(F.10) becomes

as before in the continuous-time case.

Note that this choice of ![]() is also the only one that eliminates

delay-free paths in the fundamental elements. This allows them to

be used as building blocks for explicit finite difference

schemes.

is also the only one that eliminates

delay-free paths in the fundamental elements. This allows them to

be used as building blocks for explicit finite difference

schemes.

We may still obtain the above results using the more typical value

![]() (instead of

(instead of ![]() ) in the bilinear transform. From

Eq.

) in the bilinear transform. From

Eq.![]() (F.12), it is clear that changing

(F.12), it is clear that changing ![]() amounts to a linear

frequency scaling of

amounts to a linear

frequency scaling of ![]() . Such a scaling may be compensated

by choosing the waveguide (port) impedances to be

. Such a scaling may be compensated

by choosing the waveguide (port) impedances to be

![]() (instead of

(instead of ![]() ) for the inductor, and

) for the inductor, and

![]() (instead of

(instead of

![]() ) for the capacitor.

) for the capacitor.

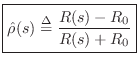

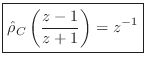

Summary of Wave Digital Elements

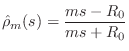

From Eq.![]() (F.1), we have that the general reflectance of impedance

(F.1), we have that the general reflectance of impedance

![]() with respect to the reference impedance

with respect to the reference impedance ![]() in the wave

variable formulation is given by

in the wave

variable formulation is given by

In WDF construction, the free constant in the bilinear transform is taken to be

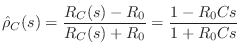

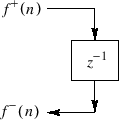

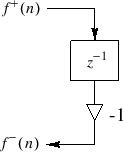

Wave Digital Mass

In the case of a mass ![]() , we have

, we have

|

Thus, the wave digital mass is simply a unit-sample delay and a negation. The fact that the value of the mass has been canceled out will be addressed below in the subsection on ``adaptors,'' i.e., it only affects interconnection with other elements. For now, just remember that the reference impedance was chosen to be equal to the mass in order to get this simple wave flow diagram. Also note that the WDF mass simulator has no delay-free path from input to output.

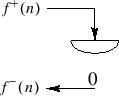

Wave Digital Spring

In the case of a spring with stiffness ![]() , we have the impedance

, we have the impedance

![$\displaystyle \fbox{$\displaystyle \hat{\tilde{\rho}}_k(z) = z^{-1}$} \qquad\makebox[0pt][l]{(Wave Digital Spring)}

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img4811.png)

Thus, the WDF of a spring is simply a unit-sample delay, which is just the negative of the WDF mass. If we were to switch to velocity waves instead of force waves, both masses and springs would again correspond to unit-sample delays, but the spring would become inverting and the mass non-inverting.

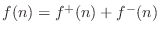

Wave Digital Dashpot

Starting with a dashpot with coefficient ![]() , we have

, we have

In the context of waveguide theory, a zero reflectance corresponds to a matched impedance, i.e., the terminating transmission-line impedance equals the characteristic impedance of the line.

The difference equation for the wave digital dashpot is simply

![]() . While this may appear overly degenerate at first,

remember that the interface to the element is a port at impedance

. While this may appear overly degenerate at first,

remember that the interface to the element is a port at impedance

![]() . Thus, in this particular case only, the infinitesimal

waveguide interface is the element itself.

. Thus, in this particular case only, the infinitesimal

waveguide interface is the element itself.

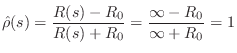

Limiting Cases

The force-wave reflectance of an infinite impedance (rigid wall or ``open circuit'') is

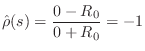

Similarly, the force-wave reflectance of a zero impedance (free termination, frictionless surface, or ``short circuit'') is

For velocity waves, we obtain the opposite results: rigid terminations are inverting, and free terminations are non-inverting.

Unit Elements

The unit element two-port is simply a bidirectional delay line with half a sample delay in each direction. As a result, it really belongs under the topic of distributed modeling. To avoid delay-free loops, Fettweis noted [135] that every pair of adaptors must be separated by at least one unit element. More recently, this objective is accomplished instead using ``reflection-free ports'' [136] (see also §F.2.2).

Next Section:

Adaptors for Wave Digital Elements

Previous Section:

Acknowledgments