Bilinear Frequency-Warping for Audio Spectrum Analysis over Bark and ERB Frequency Scales

With the increasing use of frequency-domain techniques in audio signal processing applications such as audio compression, there is increasing emphasis on psychoacoustic-based spectral measures [274,17,113,118]. In particular, frequency warping is an important tool in spectral audio signal processing. For example, audio spectrograms (Chapter 7) can display signal energy versus time over a more perceptual, nonuniform, audio frequency axis (§7.3). Also, methods for digital filter design (Chapter 4) having no weighting function versus frequency, such as linear predictive coding (LPC) (§10.3), can be given an effective weighting function by means of frequency warping [278].

A common choice of audio frequency warping in audio applications is from a linear frequency scale to a Bark frequency scale (also called ``critical band rate'') [306,307,304,179,102,269]. The Bark scale is defined so that critical bands of hearing are uniformly spaced. (One critical bandwidth equals one Bark.)

A more recently developed psychoacoustic frequency scale, called the Equivalent Rectangular Bandwidth (ERB) scale [88], is based on different psychoacoustic experiments resulting in generally narrower critical bandwidth estimates.

This appendix, condensed from [269,268],

describes a useful class approximate Bark/ERB frequency warpings that

may be implemented using a bilinear transform (first-order

conformal map of the unit circle to itself in the ![]() plane). Such

warpings preserve order in filter-design applications. That is,

the warping can be undone by the inverse bilinear transform which,

because its first order, does not change the order of the filter that

was designed over the warped frequency axis.

plane). Such

warpings preserve order in filter-design applications. That is,

the warping can be undone by the inverse bilinear transform which,

because its first order, does not change the order of the filter that

was designed over the warped frequency axis.

The Bark Frequency Scale

Based on the results of many psychoacoustic experiments, the Bark scale is defined so that the critical bands of human hearing each have a width of one Bark. By representing spectral energy (in dB) over the Bark scale, a closer correspondence is obtained with spectral information processing in the ear (§7.3).

The Bark scale ranges from 1 to 24 Barks, corresponding to the first 24 critical bands of hearing [304]. The published Bark band edges are given in Hertz as [0, 100, 200, 300, 400, 510, 630, 770, 920, 1080, 1270, 1480, 1720, 2000, 2320, 2700, 3150, 3700, 4400, 5300, 6400, 7700, 9500, 12000, 15500]. The published band centers in Hertz are [50, 150, 250, 350, 450, 570, 700, 840, 1000, 1170, 1370, 1600, 1850, 2150, 2500, 2900, 3400, 4000, 4800, 5800, 7000, 8500, 10500, 13500]. These center-frequencies and bandwidths are to be interpreted as samplings of a continuous variation in the frequency response of the ear to a sinusoid or narrow-band noise process. That is, critical-band-shaped masking patterns should be seen as forming around specific stimuli in the ear rather than being associated with a specific fixed filter bank in the ear.

Note that since the Bark scale is defined only up to 15.5 kHz, the highest sampling rate for which the Bark scale is defined up to the Nyquist limit, without requiring extrapolation, is 31 kHz. The 25th Bark band certainly extends above 19 kHz (the sum of the 24th Bark band edge and the 23rd critical bandwidth), so that a sampling rate of 40 kHz is implicitly supported by the data. We have extrapolated the Bark band-edges in our work, appending the values [20500, 27000] so that sampling rates up to 54 kHz are defined. While human hearing generally does not extend above 20 kHz, audio sampling rates as high as 48 kHz or higher are common in practice.

The Bark scale is defined above in terms of frequency in Hz versus Bark number. For computing optimal bilinear transformations, it is preferable to optimize the fit to the inverse of this map, i.e., Barks versus Hz, so that the mapping error will be measured in Barks rather than Hz.

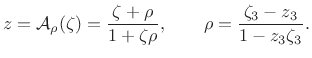

The Bilinear Transform

The formula for a general first-order (bilinear) conformal mapping of functions of a complex variable is conveniently expressed by [42, page 75]

It can be seen that choosing three specific points and their images determines the mapping for all

Bilinear transformations map circles and lines into circles and lines

(lines being viewed as circles passing through the point at infinity).

In digital audio, where both domains are ``![]() planes,'' we normally

want to map the unit circle to itself, with dc mapping to dc

(

planes,'' we normally

want to map the unit circle to itself, with dc mapping to dc

(

![]() ) and half the sampling rate mapping to half the

sampling rate (

) and half the sampling rate mapping to half the

sampling rate (

![]() ). Making these substitutions in

(E.2) leaves us with transformations of the form

). Making these substitutions in

(E.2) leaves us with transformations of the form

|

(E.1) |

The constant

![$\displaystyle \rho = {\sin\{[a(\omega )-\omega ]/2\} \over \sin\{[a(\omega )+\omega ]/2\} }.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2876.png) |

(E.2) |

In this form, it is clear that

Optimal Bilinear Bark Warping

It turns out that a first-order conformal map (bilinear transform) can provide a surprisingly close match to the Bark frequency scale [268,269]. This is shown in Fig.E.1.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fitlogf}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2882.png) |

In the following, a simple direct-form expression is developed for the

map parameter ![]() giving the best least-squares fit to a Bark scale

for a chosen sampling rate. As Fig.E.1 shows, the error is so

small that the solution is also very close to the optimal Chebyshev

fit. In fact, the

giving the best least-squares fit to a Bark scale

for a chosen sampling rate. As Fig.E.1 shows, the error is so

small that the solution is also very close to the optimal Chebyshev

fit. In fact, the ![]() optimal warping is within 0.04 Bark of the

optimal warping is within 0.04 Bark of the

![]() optimal warping. Since the experimental uncertainty when

measuring critical bands is on the order of a tenth of a Bark or more

[178,181,251,298],

we consider the optimal Chebyshev and least-squares maps to be

essentially equivalent psychoacoustically.

optimal warping. Since the experimental uncertainty when

measuring critical bands is on the order of a tenth of a Bark or more

[178,181,251,298],

we consider the optimal Chebyshev and least-squares maps to be

essentially equivalent psychoacoustically.

Computing

Our goal is to find the allpass coefficient ![]() such that the

frequency mapping

such that the

frequency mapping

best approximates the Bark scale

Using squared frequency errors to gauge the fit between

![]() and

its Bark-warped counterpart, the optimal mapping-parameter

and

its Bark-warped counterpart, the optimal mapping-parameter ![]() may

be written as

may

be written as

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*= \hbox{Arg}\left[\min_{\rho }\left\{\left\Vert\,a(\omega )- b(\omega )\,\right\Vert\right\}\right],

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2886.png)

where

is nonlinear in

has a norm which is more amenable to minimization. The first issue we address is how the minimizers of

Denote by ![]() and

and ![]() the complex representations of the

frequencies

the complex representations of the

frequencies

![]() and

and

![]() on the unit circle,

on the unit circle,

As seen in Fig.E.2, the absolute frequency error

The desired arc length error

Accordingly, essentially the same

The error

![]() is also nonlinear in the parameter

is also nonlinear in the parameter ![]() , and to find

its norm minimizer, an equation error is introduced, as is

common practice in developing solutions to nonlinear system

identification problems [152]. Consider mapping

the frequency

, and to find

its norm minimizer, an equation error is introduced, as is

common practice in developing solutions to nonlinear system

identification problems [152]. Consider mapping

the frequency

![]() via the allpass transformation

via the allpass transformation

![]() ,

,

Now, multiply (E.3.1) by the denominator

Rearranging terms, we have

where

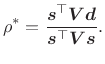

It is shown in [269] that the optimal weighted least-squares conformal map parameter estimate is given by

If the weighting matrix

![$\displaystyle \frac{\sum_{k=1}^K

v(\omega _k)

\sin\left[\frac{b(\omega_{k})-\omega_{k}}{2}\right]

\sin\left[\frac{b(\omega_{k})+\omega_{k}}{2}\right]

}{\sum_{k=1}^K

v(\omega _k)\sin^2\left[\frac{b(\omega_{k})+\omega_{k}}{2}\right]}$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2913.png) |

|||

![$\displaystyle \frac{\sum_{k=1}^{K}

v(\omega _k)

\left\{\cos\left[b(\omega_{k})\right]- \cos(\omega_{k})\right\}}{%

\sum_{k=1}^{K} v(\omega_{k}) \left\{\cos\left[b(\omega_{k}) + \omega_{k}\right]- 1\right\}}.$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2914.png) |

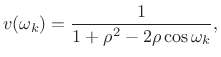

The kth diagonal element of an optimal diagonal weighting matrix

![]() is given by [269]

is given by [269]

Note that the desired weighting depends on the unknown map parameter

![]() . To overcome this difficulty, we suggest first estimating

. To overcome this difficulty, we suggest first estimating

![]() using

using

![]() , where

, where

![]() denotes the identity matrix,

and then computing

denotes the identity matrix,

and then computing ![]() using the weighting (E.3.1) based on the

unweighted solution. This is analogous to the Steiglitz-McBride

algorithm for converting an equation-error minimizer to the more

desired ``output-error'' minimizer using an iteratively computed

weight function [151].

using the weighting (E.3.1) based on the

unweighted solution. This is analogous to the Steiglitz-McBride

algorithm for converting an equation-error minimizer to the more

desired ``output-error'' minimizer using an iteratively computed

weight function [151].

Optimal Frequency Warpings

In [269], optimal allpass coefficients ![]() were

computed for sampling rates of twice the Bark band-edge frequencies by

means of four different optimization methods:

were

computed for sampling rates of twice the Bark band-edge frequencies by

means of four different optimization methods:

- Minimize the peak

arc-length error

at each sampling rate to obtain

the optimal Chebyshev allpass parameter

at each sampling rate to obtain

the optimal Chebyshev allpass parameter

.

.

- Minimize the sum of squared

arc-length errors

to obtain

the optimal least-squares allpass parameter

to obtain

the optimal least-squares allpass parameter

.

.

- Use the closed-form weighted equation-error solution

(E.3.1) computed twice, first with

,

and second with

,

and second with

set from (E.3.1) to obtain

the optimal ``weighted equation error'' solution

set from (E.3.1) to obtain

the optimal ``weighted equation error'' solution

.

.

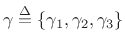

- Fit the function

![$ \gamma_1\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(\gamma_2f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}+\gamma_3 $](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2923.png) to the optimal Chebyshev allpass

parameter

to the optimal Chebyshev allpass

parameter

via Chebyshev optimization with respect to

via Chebyshev optimization with respect to

.

We will refer to the resulting function as

the ``arctangent approximation''

.

We will refer to the resulting function as

the ``arctangent approximation''

(or, less

formally, the ``Barktan formula''), and note that

it is easily computed directly from the sampling rate.

(or, less

formally, the ``Barktan formula''), and note that

it is easily computed directly from the sampling rate.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/pfs}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2927.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/rmspkerr}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2928.png) |

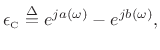

The peak and rms frequency-mapping errors are plotted versus sampling rate in Fig.E.4. Peak and rms errors in BarksE.1 are plotted for all four cases (Chebyshev, least squares, weighted equation-error, and arctangent approximation). The conformal-map fit to the Bark scale is generally excellent in all cases. We see that the rms error is essentially identical in the first three cases, although the Chebyshev rms error is visibly larger below 10 kHz. Similarly, the peak error is essentially the same for least squares and weighted equation error, with the Chebyshev case being able to shave almost 0.1 Bark from the maximum error at high sampling rates. The arctangent formula shows up to a tenth of a Bark larger peak error at sampling rates 15-30 and 54 kHz, but otherwise it performs very well; at 41 kHz and below 12 kHz the arctangent approximation is essentially optimal in all senses considered.

At sampling rates up to the maximum non-extrapolated sampling rate of ![]() kHz, the peak mapping errors are all much less than one Bark (0.64 Barks

for the Chebyshev case and 0.67 Barks for the two least squares cases).

The mapping errors in Barks can be seen to increase almost linearly with

sampling rate. However, the irregular nature of the Bark-scale data

results in a nonmonotonic relationship at lower sampling rates.

kHz, the peak mapping errors are all much less than one Bark (0.64 Barks

for the Chebyshev case and 0.67 Barks for the two least squares cases).

The mapping errors in Barks can be seen to increase almost linearly with

sampling rate. However, the irregular nature of the Bark-scale data

results in a nonmonotonic relationship at lower sampling rates.

The specific frequency mapping errors versus frequency at the ![]() kHz

sampling rate (the same case shown in Fig.E.1) are plotted in

Fig.E.5. Again, all four cases are overlaid, and again the least

squares and weighted equation-error cases are essentially identical.

By forcing equal and opposite peak errors, the Chebyshev case is able

to lower the peak error from 0.67 to 0.64 Barks. A difference of 0.03

Barks is probably insignificant for most applications. The peak

errors occur at 1.3 kHz and 8.8 kHz where the error is approximately

2/3 Bark. The arctangent formula peak error is 0.73 Barks at 8.8 kHz,

but in return, its secondary error peak at 1.3 kHz is only 0.55 Barks.

In some applications, such as when working with oversampled signals,

higher accuracy at low frequencies at the expense of higher error at

very high frequencies may be considered a desirable tradeoff.

kHz

sampling rate (the same case shown in Fig.E.1) are plotted in

Fig.E.5. Again, all four cases are overlaid, and again the least

squares and weighted equation-error cases are essentially identical.

By forcing equal and opposite peak errors, the Chebyshev case is able

to lower the peak error from 0.67 to 0.64 Barks. A difference of 0.03

Barks is probably insignificant for most applications. The peak

errors occur at 1.3 kHz and 8.8 kHz where the error is approximately

2/3 Bark. The arctangent formula peak error is 0.73 Barks at 8.8 kHz,

but in return, its secondary error peak at 1.3 kHz is only 0.55 Barks.

In some applications, such as when working with oversampled signals,

higher accuracy at low frequencies at the expense of higher error at

very high frequencies may be considered a desirable tradeoff.

We see that the mapping falls ``behind'' a bit as frequency increases

from zero to 1.3 kHz, mapping linear frequencies slightly below the

desired corresponding Bark values; then, the mapping ``catches up,''

reaching an error of 0 Barks near 3 kHz. Above 3 kHz, it gets

``ahead'' slightly, with frequencies in Hz being mapped a little too

high, reaching the positive error peak at 8.8 kHz, after which it

falls back down to zero error at

![]() . (Recall that dc and

half the sampling-rate are always points of zero error by

construction.)

. (Recall that dc and

half the sampling-rate are always points of zero error by

construction.)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/rbe}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2935.png) |

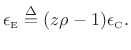

Bark Relative Bandwidth Mapping Error

The slope of the frequency versus warped-frequency curve can be

interpreted as being proportional to critical bandwidth, since a unit

interval (one Bark) on the warped-frequency axis is magnified by the slope

to restore the band to its original size (one critical bandwidth). It is

therefore interesting to look at the relative slope error, i.e., the

error in the slope of the frequency mapping divided by the ideal Bark-map

slope. We interpret this error measure as the relative

bandwidth-mapping error (RBME). The RBME is plotted in Fig.E.6 for

a ![]() kHz sampling rate. The worst case is 21% for the Chebyshev case

and 20% for both least-squares cases. When the mapping coefficient is

explicitly optimized to minimize RBME, the results of Fig.E.7 are

obtained: the Chebyshev peak error drops from 21% down to 18%, while the

least-squares cases remain unchanged at 20% maximum RBME. A 3% change in

RBME is comparable to the 0.03 Bark peak-error reduction seen in

Fig.E.5 when using the Chebyshev norm instead of the

kHz sampling rate. The worst case is 21% for the Chebyshev case

and 20% for both least-squares cases. When the mapping coefficient is

explicitly optimized to minimize RBME, the results of Fig.E.7 are

obtained: the Chebyshev peak error drops from 21% down to 18%, while the

least-squares cases remain unchanged at 20% maximum RBME. A 3% change in

RBME is comparable to the 0.03 Bark peak-error reduction seen in

Fig.E.5 when using the Chebyshev norm instead of the ![]() norm;

again, such a small difference is not likely to be significant in most

applications.

norm;

again, such a small difference is not likely to be significant in most

applications.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/pkrbmeslp}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2937.png) |

Similar observations are obtained at other sampling rates, as shown in Fig.E.8. Near a 10 kHz sampling rate, the Chebyshev RBME is reduced from 17% when minimizing absolute error in Barks (not shown in any figure) to around 12% by explicitly minimizing the RBME, and this is the sampling-rate range of maximum benefit. At 15.2, 19, 41, and 54 kHz sampling rates, the difference is on the order of only 1%. Other cases generally lie between these extremes. The arctangent formula generally falls between the Chebyshev and optimal least-squares cases, except at the highest (extrapolated) sampling rate 54 kHz. The rms error is very similar in all four cases, although the Chebyshev case has a little larger rms error near a 10 kHz sampling rate, and the arctangent case gives a noticeably larger rms error at 54 kHz.

Error Significance

In one study, young normal listeners exhibited a standard deviation in their measured auditory bandwidths (based on notched-noise masking experiments) on the order of 10% of center frequency [178]. Therefore, a 20% peak error in mapped bandwidth (typical for sampling rates approaching 40 kHz) could be considered significant. However, the range of auditory-filter bandwidths measured in 93 young normal subjects at 2 kHz [178] was 230 to 410 Hz, which is -26% to +32% relative to 310 Hz. In [298], 40 subjects were measured, yielding auditory-filter bandwidths between -33% and +65%, with a standard deviation of 18%. It may thus be concluded that a worst-case mapping error on the order of 20%, while probably detectable by ``golden ears'' listeners, lies well within the range of experimental deviations in the empirical measurement of auditory bandwidth.

As a worst-case example of how the 18% peak bandwidth-mapping error in Fig.E.7 might correspond to an audible distortion, consider one critical band of noise centered at the frequency of maximum negative mapping error, scaled to be the same loudness as a single critical band of noise centered at the frequency of maximum positive error. The systematic nature of the mapping error results in a narrowing of the lower band and expansion of the upper band by about 1.7 dB. As a result, over the warped frequency axis, the upper band will be effectively emphasized over the lower band by about 3 dB.

Arctangent Approximations for

This subsection provides further details on the arctangent approximation for the optimal allpass coefficient as a function of sampling rate. Compared with other spline or polynomial approximations, the arctangent form

was found to provide a more parsimonious expression at a given accuracy level. The idea was that the arctangent function provided a mapping from the interval

![$\displaystyle f_s= {1\over \gamma_2}\tan\left[{\pi\over2} \left(\frac{\rho _{\mathbf\gamma}- \gamma_3}{\gamma_1}\right)^2\right].

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2945.png)

To obtain the optimal arctangent form

![]() , the expression for

, the expression for

![]() in (E.3.5) was optimized with respect to its free

parameters

in (E.3.5) was optimized with respect to its free

parameters

![]() to match the optimal

Chebyshev allpass coefficient as a function of sampling rate:

to match the optimal

Chebyshev allpass coefficient as a function of sampling rate:

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*_{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) \isdef \hbox{Arg}\left[\min_{{\mathbf\gamma}}\left\{\left\Vert\,\rho ^*_\infty(f_s) - \rho _{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s)\,\right\Vert _\infty\right\}\right].

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2947.png)

For a Bark warping, the optimized arctangent formula was found to be

where

When the optimality criterion is chosen to minimize relative bandwidth mapping error (relative map slope error), the arctangent formula optimization yields

The performance of this formula is shown in Fig.E.8. It tends to follow the performance of the optimal least squares map parameter even though the peak parameter error was minimized relative to the optimal Chebyshev map. At 54 kHz there is an additional 3% bandwidth error due to the arctangent approximation, and near 10 kHz the additional error is about 4%; at other sampling rates, the performance of the RBME arctangent approximation is better, and like (E.3.5), it is extremely accurate at 41 kHz.

Application to Audio Filter Design

Frequency warping is generally employed in audio filter design by

- warping the desired frequency response, thus ``horizontally stretching'' the more important low-frequency region of the spectrum.

- performing a filter design over the warped frequency axis, and

- transforming the resulting filter to eliminate the frequency warp, returning it to the normal frequency axis.

Filter Design Example

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fd}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2950.png) |

We conclude discussion of the Bark bilinear transform with the filter

design example of Fig.E.9. A ![]() th-order pole-zero filter was fit

using Prony's method [162] to the equalization function plotted in the

figure as a dashed line. Prony's method was applied normally over a

uniformly sampled linear frequency grid in the example of

Fig.E.9a, and over an approximate Bark-scale axis in the example

of Fig.E.9b. The procedure in the Bark-scale case was as

follows [258]:E.2

th-order pole-zero filter was fit

using Prony's method [162] to the equalization function plotted in the

figure as a dashed line. Prony's method was applied normally over a

uniformly sampled linear frequency grid in the example of

Fig.E.9a, and over an approximate Bark-scale axis in the example

of Fig.E.9b. The procedure in the Bark-scale case was as

follows [258]:E.2

- The optimal allpass coefficient

was found using

(E.3.5).

was found using

(E.3.5).

- The desired frequency response

defined on a linear

frequency axis

defined on a linear

frequency axis  was warped to an approximate Bark scale

was warped to an approximate Bark scale

using the Bark bilinear transform,

using the Bark bilinear transform,

![$ {\tilde H}(e^{j\omega }) \isdef H[{\cal A}_{\rho }(e^{ja(\omega )})]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2951.png) .

.

- A parametric ARMA model

was fit to the desired

Bark-warped frequency response

was fit to the desired

Bark-warped frequency response

over the unit circle

over the unit circle

.

.

- Finally, the inverse Bark bilinear transform

was used to ``unwarp'' the modeled system to a linear frequency axis.

was used to ``unwarp'' the modeled system to a linear frequency axis.

Referring to Fig.E.9, it is clear that the warped solution provides a

better overall fit than the direct solution which sacrifices accuracy below

![]() kHz to achieve a tighter fit above

kHz to achieve a tighter fit above ![]() kHz. In some part, the spacing

of spectral features is responsible for the success of the Bark-warped

model in this particular example. However, we generally recommend using

the Bark bilinear transform to design audio filters, since doing so weights

the error norm (for norms other than Chebyshev types) in a way which gives

equal importance to matching features having equal Bark bandwidths. Even

in the case of Chebyshev optimization, auditory warping appears to improve

the numerical conditioning of the filter design problem; this applies

also to optimization under the Hankel norm which includes an optimal

Chebyshev design internally as an intermediate step. Further filter-design

examples, including more on the Hankel-norm case, may be found in

[258].

kHz. In some part, the spacing

of spectral features is responsible for the success of the Bark-warped

model in this particular example. However, we generally recommend using

the Bark bilinear transform to design audio filters, since doing so weights

the error norm (for norms other than Chebyshev types) in a way which gives

equal importance to matching features having equal Bark bandwidths. Even

in the case of Chebyshev optimization, auditory warping appears to improve

the numerical conditioning of the filter design problem; this applies

also to optimization under the Hankel norm which includes an optimal

Chebyshev design internally as an intermediate step. Further filter-design

examples, including more on the Hankel-norm case, may be found in

[258].

Equivalent Rectangular Bandwidth

It also turns out that a first-order conformal map (bilinear transform) can provide a good match to the ERB scale [269] as well. Moore and Glasberg [177] have revised Zwicker's loudness model to better explain (1) how equal-loudness contours change as a function of level, (2) why loudness remains constant as the bandwidth of a fixed-intensity sound increases up to the critical bandwidth, and (3) the loudness of partially masked sounds. The modification that is relevant here is the replacement of the Bark scale by the equivalent rectangular bandwidth (ERB) scale. The ERB of the auditory filter is assumed to be closely related to the critical bandwidth, but it is measured using the notched-noise method [205,206,251,181,87] rather than on classical masking experiments involving a narrow-band masker and probe tone [306,307,304]. As a result, the ERB is said not to be affected by the detection of beats or intermodulation products between the signal and masker. Since this scale is defined analytically, it is also more smoothly behaved than the Bark scale data.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/erbbark}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2956.png) |

At moderate sound levels, the ERB in Hz is defined by [177]

where

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/erbbarkm}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2963.png) |

The ERB scale is defined as the number of ERBs below each frequency

for

Proceeding in the same manner as for the Bark-scale case, allpass coefficients giving a best approximation to the ERB-scale warping were computed for sampling rates near twice the Bark band edge frequencies (chosen to facilitate comparison between the ERB and Bark cases). The resulting optimal map coefficients are shown in Fig.E.12. The allpass parameter increases with increasing sampling rate, as in the Bark-scale case, but it covers a significantly narrower range, as a comparison with Fig.E.3 shows. Also, the Chebyshev solution is now systematically larger than the least-squares solutions, and the least-squares and weighted equation-error cases are no longer essentially identical. The fact that the arctangent formula is optimized for the Chebyshev case is much more evident in the error plot of Fig.E.12b than it was in Fig.E.3b for the Bark warping parameter.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/pfserb}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2965.png) |

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/rmspkerrerb}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2966.png) |

The peak and rms mapping errors are plotted versus sampling rate in Fig.E.13. Compare these results for the ERB scale with those for the Bark scale in Fig.E.4. The ERB map errors are plotted in Barks to facilitate comparison. The rms error of the conformal map fit to the ERB scale increases nearly linearly with log-sampling-rate. The ERB-scale error increases very smoothly with frequency while the Bark-scale error is non-monotonic (see Fig.E.4). The smoother behavior of the ERB errors appears due in part to the fact that the ERB scale is defined analytically while the Bark scale is defined more directly in terms of experimental data: The Bark-scale fit is so good as to be within experimental deviation, while the ERB-scale fit has a much larger systematic error component. The peak error in Fig.E.13 also grows close to linearly on a log-frequency scale and is similarly two to three times the Bark-scale errors of Fig.E.4.

The frequency mapping errors are plotted versus frequency in

Fig.E.14 for a sampling rate of ![]() kHz. Unlike the Bark-scale

case in Fig.E.5, there is now a visible difference between the

weighted equation-error and optimal least-squares mappings for the ERB

scale. The figure shows also that the peak error when warping to an ERB

scale is about three times larger than the peak error when warping to the

Bark scale, growing from 0.64 Barks to 1.9 Barks. The locations of the

peak errors are also at lower frequencies (moving from 1.3 and 8.8 kHz in

the Bark-scale case to 0.7 and 8.2 kHz in the ERB-scale case).

kHz. Unlike the Bark-scale

case in Fig.E.5, there is now a visible difference between the

weighted equation-error and optimal least-squares mappings for the ERB

scale. The figure shows also that the peak error when warping to an ERB

scale is about three times larger than the peak error when warping to the

Bark scale, growing from 0.64 Barks to 1.9 Barks. The locations of the

peak errors are also at lower frequencies (moving from 1.3 and 8.8 kHz in

the Bark-scale case to 0.7 and 8.2 kHz in the ERB-scale case).

ERB Relative Bandwidth Mapping Error

The optimal relative bandwidth-mapping error (RBME) for the ERB case is

plotted in Fig.E.15 for a ![]() kHz sampling rate. The peak

error has grown from close to 20% for the Bark-scale case to more than

60% for the ERB case. Thus, frequency intervals are mapped to the ERB

scale with up to three times as much relative error (60%) as when mapping

to the Bark scale (20%).

The continued narrowing of the auditory filter bandwidth as frequency decreases

on the ERB scale results in the conformal map not being able to supply

sufficient stretching of the low-frequency axis. The Bark scale case, on

the other hand, is much better provided at low frequencies by the

first-order conformal map.

kHz sampling rate. The peak

error has grown from close to 20% for the Bark-scale case to more than

60% for the ERB case. Thus, frequency intervals are mapped to the ERB

scale with up to three times as much relative error (60%) as when mapping

to the Bark scale (20%).

The continued narrowing of the auditory filter bandwidth as frequency decreases

on the ERB scale results in the conformal map not being able to supply

sufficient stretching of the low-frequency axis. The Bark scale case, on

the other hand, is much better provided at low frequencies by the

first-order conformal map.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/pkrbmeerbslp}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2969.png) |

Figure E.16 shows the rms and peak ERB RBME as a function of sampling rate. Near a 10 kHz sampling rate, for example, the Chebyshev ERB RBME is increased from 12% in the Bark-scale case to around 37%, again a tripling of the peak error. We can also see in Fig.E.16 that the arctangent formula gives a very good approximation to the optimal Chebyshev solution at all sampling rates. The optimal least-squares and weighted equation-error solutions are quite different, with the weighted equation-error solution moving from being close to the least-squares solution at low sampling rates, to being close to the Chebyshev solution at the higher sampling rates. The rms error is very similar in all four cases, as it was in the Bark-scale case, although the Chebyshev and arctangent formula solutions show noticeable increase in the rms error at low sampling rates where they also show a reduction in peak error by 5% or so.

Arctangent Approximations for

, ERB Case

, ERB Case

For an approximation to the optimal Chebyshev ERB frequency mapping, the arctangent formula becomes

where

When the optimality criterion is chosen to minimize relative bandwidth mapping error in the ERB case, the arctangent formula optimization yields

The performance of this formula is shown in Fig.E.16. It follows the optimal Chebyshev map parameter very well.

Directions for Improvements

Audio conformal maps can be adjusted by using a more general error

weighting versus frequency. For example, the weighting can be set to

zero above some frequency limit along the unit circle. A more general

weighting can also be used to obtain improved accuracy in specific

desired frequency ranges. Again, these refinements would seem to be

of interest primarily for the ERB-scale and other mappings, since the

Bark-scale warping is excellent already. The diagonal weighting matrix

![]() in the weighted equation error solution (E.3.1) can be

multiplied by any desired application-dependent weighting.

in the weighted equation error solution (E.3.1) can be

multiplied by any desired application-dependent weighting.

As another variation, an auditory frequency scale could be defined

based on the cochlear frequency-to-place function [96].

In this case, a close relationship still exists between equal-place

increments along the basilar membrane and equal bandwidth increments

in the defined audio filter bank. Preliminary comparisons

[96, Fig. 9] indicate that the first-order conformal map

errors for this case are qualitatively between the ERB and Bark-scale

cases. The first-order conformal map works best when the auditory

filter bandwidths level off to a minimum width at low frequencies, as

they do in the Bark-scale case below ![]() Hz. Thus, the question of

the ``audio fidelity'' of the first-order conformal map is directly

tied to the question of what is really the best frequency resolution

to provide at low frequencies in the auditory filter bank.

Hz. Thus, the question of

the ``audio fidelity'' of the first-order conformal map is directly

tied to the question of what is really the best frequency resolution

to provide at low frequencies in the auditory filter bank.

Summary

The first-order ``allpass'' conformal map which maps the unit circle to itself was configured to approximate frequency warpings from a linear frequency scale to either a Bark scale or an ERB frequency scale for a wide variety of sampling rates. The accuracy of this warping is extremely good for the Bark-scale case, and fair also for the ERB case; the first-order conformal map shows significantly more error in the ERB case (about three times that of the Bark-scale case) due to its narrower resolution bandwidths at low frequencies.

A closed-form expression was derived for the allpass coefficient which minimizes the norm of the weighted equation error between samples of the allpass warping and the desired Bark or ERB warpings. The weighting function was designed to give estimates as close as possible to the optimal least-squares estimate, and comparisons showed this to be well achieved, especially in the Bark-scale case.

A simple, closed-form, invertible expression which comes very close to the optimal Chebyshev allpass coefficient vs. sampling rate was given in (E.3.5) for the Bark-scale case and in (E.5.2) for the ERB-scale case.

Three optimal conformal maps were defined based on Chebyshev, least

squares, and weighted equation-error approximation, and all three

mappings were found to be psychoacoustically identical, for most

practical purposes, in the Bark-scale case. When using optimal maps,

the peak relative bandwidth mapping error is about ![]() % in the

Bark-scale case and

% in the

Bark-scale case and ![]() % in the ERB-scale case.

% in the ERB-scale case.

We conclude that the first-order conformal map is a highly useful tool

for audio digital filter design and related applications in digital

audio signal processing which may benefit from an order-invariant

mapping of the unit circle from a linear frequency scale to an

approximate auditory frequency scale.

Matlab code for plots, optimizations, and the filter design example

presented here are available online at

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/bbt/bbt.html

Next Section:

Examples in Matlab and Octave

Previous Section:

Gaussian Function Properties

![\includegraphics[width=3in]{eps/eaec}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2893.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fme}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2933.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/rbeslp}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2936.png)

![$\displaystyle \rho _{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) \isdef \max\left\{0,\gamma_1\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(\gamma_2f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}+\gamma_3 \right\}

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2938.png)

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*_{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) = 1.0674\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(0.06583f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}-0.1916,

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2948.png)

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*_{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) = 1.0480\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(0.07212f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}-0.1957.

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2949.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fmeerb}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2967.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/rbeerbslp}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2968.png)

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*_{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) = 0.7446\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(0.1418f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}+0.03237,

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2970.png)

![$\displaystyle \rho ^*_{\mathbf\gamma}(f_s) = 0.7164\left[{2\over\pi}\arctan(0.09669f_s)\right]^{{1\over2}}+0.08667.

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/sasp2/img2971.png)