Complex Sinusoids

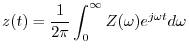

Recall Euler's Identity,

Circular Motion

Since the modulus of the complex sinusoid is constant, it must lie on a circle in the complex plane. For example,

We may call a complex sinusoid

![]() a

positive-frequency sinusoid when

a

positive-frequency sinusoid when ![]() . Similarly, we

may define a complex sinusoid of the form

. Similarly, we

may define a complex sinusoid of the form

![]() , with

, with

![]() , to be a

negative-frequency sinusoid. Note that a positive- or

negative-frequency sinusoid is necessarily complex.

, to be a

negative-frequency sinusoid. Note that a positive- or

negative-frequency sinusoid is necessarily complex.

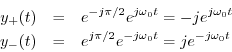

Projection of Circular Motion

Interpreting the real and imaginary parts of the complex sinusoid,

in the complex plane, we see that sinusoidal motion is the

projection of circular motion onto any straight line. Thus, the

sinusoidal motion

![]() is the projection of the circular

motion

is the projection of the circular

motion

![]() onto the

onto the ![]() (real-part) axis, while

(real-part) axis, while

![]() is the projection of

is the projection of

![]() onto the

onto the ![]() (imaginary-part) axis.

(imaginary-part) axis.

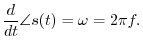

Figure 4.9 shows a plot of a complex sinusoid versus time, along with its

projections onto coordinate planes. This is a 3D plot showing the

![]() -plane versus time. The axes are the real part, imaginary part, and

time. (Or we could have used magnitude and phase versus time.)

-plane versus time. The axes are the real part, imaginary part, and

time. (Or we could have used magnitude and phase versus time.)

Note that the left projection (onto the ![]() plane) is a circle, the lower

projection (real-part vs. time) is a cosine, and the upper projection

(imaginary-part vs. time) is a sine. A point traversing the plot projects

to uniform circular motion in the

plane) is a circle, the lower

projection (real-part vs. time) is a cosine, and the upper projection

(imaginary-part vs. time) is a sine. A point traversing the plot projects

to uniform circular motion in the ![]() plane, and sinusoidal motion on the

two other planes.

plane, and sinusoidal motion on the

two other planes.

Positive and Negative Frequencies

In §2.9, we used Euler's Identity to show

Setting

![]() , we see that both sine and cosine (and

hence all real sinusoids) consist of a sum of equal and opposite circular

motion. Phrased differently, every real sinusoid consists of an equal

contribution of positive and negative frequency components. This is true

of all real signals. When we get to spectrum analysis, we will find that

every real signal contains equal amounts of positive and negative

frequencies, i.e., if

, we see that both sine and cosine (and

hence all real sinusoids) consist of a sum of equal and opposite circular

motion. Phrased differently, every real sinusoid consists of an equal

contribution of positive and negative frequency components. This is true

of all real signals. When we get to spectrum analysis, we will find that

every real signal contains equal amounts of positive and negative

frequencies, i.e., if ![]() denotes the spectrum of the real signal

denotes the spectrum of the real signal

![]() , we will always have

, we will always have

![]() .

.

Note that, mathematically, the complex sinusoid

![]() is really simpler and more basic than the real

sinusoid

is really simpler and more basic than the real

sinusoid

![]() because

because

![]() consists of

one frequency

consists of

one frequency ![]() while

while

![]() really consists of two

frequencies

really consists of two

frequencies ![]() and

and ![]() . We may think of a real sinusoid

as being the sum of a positive-frequency and a negative-frequency

complex sinusoid, so in that sense real sinusoids are ``twice as

complicated'' as complex sinusoids. Complex sinusoids are also nicer

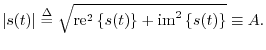

because they have a constant modulus. ``Amplitude envelope

detectors'' for complex sinusoids are trivial: just compute the square

root of the sum of the squares of the real and imaginary parts to

obtain the instantaneous peak amplitude at any time. Frequency

demodulators are similarly trivial: just differentiate the phase of

the complex sinusoid to obtain its instantaneous frequency. It

should therefore come as no surprise that signal processing engineers

often prefer to convert real sinusoids into complex sinusoids (by

filtering out the negative-frequency component) before processing them

further.

. We may think of a real sinusoid

as being the sum of a positive-frequency and a negative-frequency

complex sinusoid, so in that sense real sinusoids are ``twice as

complicated'' as complex sinusoids. Complex sinusoids are also nicer

because they have a constant modulus. ``Amplitude envelope

detectors'' for complex sinusoids are trivial: just compute the square

root of the sum of the squares of the real and imaginary parts to

obtain the instantaneous peak amplitude at any time. Frequency

demodulators are similarly trivial: just differentiate the phase of

the complex sinusoid to obtain its instantaneous frequency. It

should therefore come as no surprise that signal processing engineers

often prefer to convert real sinusoids into complex sinusoids (by

filtering out the negative-frequency component) before processing them

further.

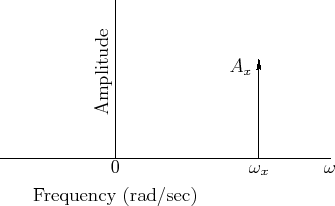

Plotting Complex Sinusoids versus Frequency

As discussed in the previous section, we regard the signal

figure[htbp]

More generally, however, a complex sinusoid has both an amplitude and

a phase (or, equivalently, a complex amplitude):

More generally, however, a complex sinusoid has both an amplitude and

a phase (or, equivalently, a complex amplitude):

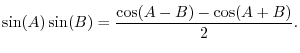

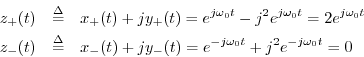

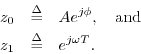

Sinusoidal Amplitude Modulation (AM)

It is instructive to study the modulation of one sinusoid by another. In this section, we will look at sinusoidal Amplitude Modulation (AM). The general AM formula is given by

In the case of sinusoidal AM, we have

Periodic amplitude modulation of this nature is often called the tremolo effect when

Let's analyze the second term of Eq.![]() (4.1) for the case of sinusoidal

AM with

(4.1) for the case of sinusoidal

AM with ![]() and

and

![]() :

:

An example waveform is shown in Fig.4.11 for

When ![]() is small (say less than

is small (say less than ![]() radians per second, or

10 Hz), the signal

radians per second, or

10 Hz), the signal ![]() is heard as a ``beating sine wave'' with

is heard as a ``beating sine wave'' with

![]() beats per second. The beat rate is

twice the modulation frequency because both the positive and negative

peaks of the modulating sinusoid cause an ``amplitude swell'' in

beats per second. The beat rate is

twice the modulation frequency because both the positive and negative

peaks of the modulating sinusoid cause an ``amplitude swell'' in

![]() . (One period of modulation--

. (One period of modulation--![]() seconds--is shown in

Fig.4.11.) The sign inversion during the negative peaks is not

normally audible.

seconds--is shown in

Fig.4.11.) The sign inversion during the negative peaks is not

normally audible.

Recall the trigonometric identity for a sum of angles:

These two sinusoidal components at the sum and difference frequencies of the modulator and carrier are called side bands of the carrier wave at frequency

Equation (4.3) expresses ![]() as a ``beating sinusoid'', while

Eq.

as a ``beating sinusoid'', while

Eq.![]() (4.4) expresses as it two unmodulated sinusoids at

frequencies

(4.4) expresses as it two unmodulated sinusoids at

frequencies

![]() . Which case do we hear?

. Which case do we hear?

It turns out we hear ![]() as two separate tones (Eq.

as two separate tones (Eq.![]() (4.4))

whenever the side bands are resolved by the ear. As

mentioned in §4.1.2,

the ear performs a ``short time Fourier analysis'' of incoming sound

(the basilar membrane in the cochlea acts as a mechanical

filter bank). The

resolution of this filterbank--its ability to discern two

separate spectral peaks for two sinusoids closely spaced in

frequency--is determined by the

critical bandwidth of hearing

[45,76,87]. A critical

bandwidth is roughly 15-20% of the band's center-frequency, over most

of the audio range [71]. Thus, the side bands in

sinusoidal AM are heard as separate tones when they are both in the

audio range and separated by at least one critical bandwidth. When

they are well inside the same critical band, ``beating'' is heard. In

between these extremes, near separation by a critical-band, the

sensation is often described as ``roughness'' [29].

(4.4))

whenever the side bands are resolved by the ear. As

mentioned in §4.1.2,

the ear performs a ``short time Fourier analysis'' of incoming sound

(the basilar membrane in the cochlea acts as a mechanical

filter bank). The

resolution of this filterbank--its ability to discern two

separate spectral peaks for two sinusoids closely spaced in

frequency--is determined by the

critical bandwidth of hearing

[45,76,87]. A critical

bandwidth is roughly 15-20% of the band's center-frequency, over most

of the audio range [71]. Thus, the side bands in

sinusoidal AM are heard as separate tones when they are both in the

audio range and separated by at least one critical bandwidth. When

they are well inside the same critical band, ``beating'' is heard. In

between these extremes, near separation by a critical-band, the

sensation is often described as ``roughness'' [29].

Example AM Spectra

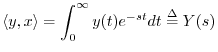

Equation (4.4) can be used to write down the spectral representation of

![]() by inspection, as shown in Fig.4.12. In the example

of Fig.4.12, we have

by inspection, as shown in Fig.4.12. In the example

of Fig.4.12, we have ![]() Hz and

Hz and ![]() Hz,

where, as always,

Hz,

where, as always,

![]() . For comparison, the spectral

magnitude of an unmodulated

. For comparison, the spectral

magnitude of an unmodulated ![]() Hz sinusoid is shown in

Fig.4.6. Note in Fig.4.12 how each of the two

sinusoidal components at

Hz sinusoid is shown in

Fig.4.6. Note in Fig.4.12 how each of the two

sinusoidal components at ![]() Hz have been ``split'' into two

``side bands'', one

Hz have been ``split'' into two

``side bands'', one ![]() Hz higher and the other

Hz higher and the other ![]() Hz lower, that

is,

Hz lower, that

is,

![]() . Note also how the

amplitude of the split component is divided equally among its

two side bands.

. Note also how the

amplitude of the split component is divided equally among its

two side bands.

Recall that ![]() was defined as the second term of

Eq.

was defined as the second term of

Eq.![]() (4.1). The first term is simply the original unmodulated

signal. Therefore, we have effectively been considering AM with a

``very large'' modulation index. In the more general case of

Eq.

(4.1). The first term is simply the original unmodulated

signal. Therefore, we have effectively been considering AM with a

``very large'' modulation index. In the more general case of

Eq.![]() (4.1) with

(4.1) with ![]() given by Eq.

given by Eq.![]() (4.2), the magnitude of

the spectral representation appears as shown in Fig.4.13.

(4.2), the magnitude of

the spectral representation appears as shown in Fig.4.13.

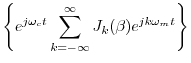

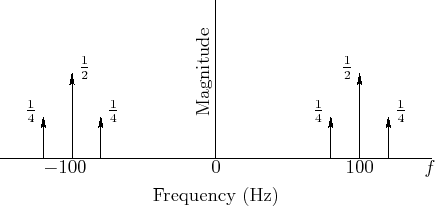

Sinusoidal Frequency Modulation (FM)

Frequency Modulation (FM) is well known as the broadcast signal format for FM radio. It is also the basis of the first commercially successful method for digital sound synthesis. Invented by John Chowning [14], it was the method used in the the highly successful Yamaha DX-7 synthesizer, and later the Yamaha OPL chip series, which was used in all ``SoundBlaster compatible'' multimedia sound cards for many years. At the time of this writing, descendants of the OPL chips remain the dominant synthesis technology for ``ring tones'' in cellular telephones.

A general formula for frequency modulation of one sinusoid by another can be written as

where the parameters

Figure 4.14 shows a unit generator patch diagram [42] for brass-like FM synthesis. For brass-like sounds, the modulation amount increases with the amplitude of the signal. In the patch, note that the amplitude envelope for the carrier oscillator is scaled and also used to control amplitude of the modulating oscillator.

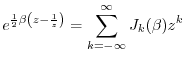

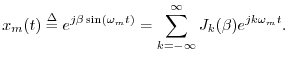

It is well known that sinusoidal frequency-modulation of a sinusoid

creates sinusoidal components that are uniformly spaced in frequency

by multiples of the modulation frequency, with amplitudes given by the

Bessel functions of the first kind [14].

As a special case, frequency-modulation of a sinusoid by itself

generates a harmonic spectrum in which the ![]() th harmonic amplitude is

proportional to

th harmonic amplitude is

proportional to

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the order of the

Bessel function and

is the order of the

Bessel function and ![]() is the FM index. We will derive

this in the next section.4.9

is the FM index. We will derive

this in the next section.4.9

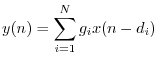

Bessel Functions

The Bessel functions of the first kind may be defined as the

coefficients

![]() in the two-sided Laurent expansion

of the so-called

generating function

[84, p. 14],4.10

in the two-sided Laurent expansion

of the so-called

generating function

[84, p. 14],4.10

where

The last expression can be interpreted as the Fourier superposition of the sinusoidal harmonics of

Note that

![]() is real when

is real when ![]() is real. This can be seen

by viewing Eq.

is real. This can be seen

by viewing Eq.![]() (4.6) as the product of the series expansion for

(4.6) as the product of the series expansion for

![]() times that for

times that for

![]() (see footnote

pertaining to Eq.

(see footnote

pertaining to Eq.![]() (4.6)).

(4.6)).

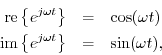

Figure 4.15 illustrates the first eleven Bessel functions of the first

kind for arguments up to ![]() . It can be seen in the figure

that when the FM index

. It can be seen in the figure

that when the FM index ![]() is zero,

is zero, ![]() and

and ![]() for

all

for

all ![]() . Since

. Since

![]() is the amplitude of the carrier

frequency, there are no side bands when

is the amplitude of the carrier

frequency, there are no side bands when ![]() . As the FM index

increases, the sidebands begin to grow while the carrier term

diminishes. This is how FM synthesis produces an expanded, brighter

bandwidth as the FM index is increased.

. As the FM index

increases, the sidebands begin to grow while the carrier term

diminishes. This is how FM synthesis produces an expanded, brighter

bandwidth as the FM index is increased.

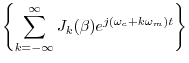

FM Spectra

Using the expansion in Eq.![]() (4.7), it is now easy to determine

the spectrum of sinusoidal FM. Eliminating scaling and

phase offsets for simplicity in Eq.

(4.7), it is now easy to determine

the spectrum of sinusoidal FM. Eliminating scaling and

phase offsets for simplicity in Eq.![]() (4.5) yields

(4.5) yields

where we have changed the modulator amplitude

| re |

|||

| re |

|||

re |

|||

re |

|||

![$\displaystyle \sum_{k=-\infty}^\infty J_k(\beta) \cos[(\omega_c+k\omega_m) t]$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img545.png) |

(4.9) |

where we used the fact that

Analytic Signals and Hilbert Transform Filters

A signal which has no negative-frequency components is called an

analytic signal.4.12 Therefore, in continuous time, every analytic signal

![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

Any real sinusoid

![]() may be converted to a

positive-frequency complex sinusoid

may be converted to a

positive-frequency complex sinusoid

![]() by simply generating a phase-quadrature component

by simply generating a phase-quadrature component

![]() to serve as the ``imaginary part'':

to serve as the ``imaginary part'':

For more complicated signals which are expressible as a sum of many

sinusoids, a filter can be constructed which shifts each

sinusoidal component by a quarter cycle. This is called a

Hilbert transform filter. Let

![]() denote the output

at time

denote the output

at time ![]() of the Hilbert-transform filter applied to the signal

of the Hilbert-transform filter applied to the signal ![]() .

Ideally, this filter has magnitude

.

Ideally, this filter has magnitude ![]() at all frequencies and

introduces a phase shift of

at all frequencies and

introduces a phase shift of ![]() at each positive frequency and

at each positive frequency and

![]() at each negative frequency. When a real signal

at each negative frequency. When a real signal ![]() and

its Hilbert transform

and

its Hilbert transform

![]() are used to form a new complex signal

are used to form a new complex signal

![]() ,

the signal

,

the signal ![]() is the (complex) analytic signal corresponding to

the real signal

is the (complex) analytic signal corresponding to

the real signal ![]() . In other words, for any real signal

. In other words, for any real signal ![]() , the

corresponding analytic signal

, the

corresponding analytic signal

![]() has the property

that all ``negative frequencies'' of

has the property

that all ``negative frequencies'' of ![]() have been ``filtered out.''

have been ``filtered out.''

To see how this works, recall that these phase shifts can be impressed on a

complex sinusoid by multiplying it by

![]() . Consider

the positive and negative frequency components at the particular frequency

. Consider

the positive and negative frequency components at the particular frequency

![]() :

:

Now let's apply a ![]() degrees phase shift to the positive-frequency

component, and a

degrees phase shift to the positive-frequency

component, and a ![]() degrees phase shift to the negative-frequency

component:

degrees phase shift to the negative-frequency

component:

Adding them together gives

and sure enough, the negative frequency component is filtered out. (There is also a gain of 2 at positive frequencies.)

For a concrete example, let's start with the real sinusoid

The analytic signal is then

![\includegraphics[width=2.8in]{eps/sineFD}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img576.png) |

Figure 4.16 illustrates what is going on in the frequency domain.

At the top is a graph of the spectrum of the sinusoid

![]() consisting of impulses at frequencies

consisting of impulses at frequencies

![]() and

zero at all other frequencies (since

and

zero at all other frequencies (since

![]() ). Each impulse

amplitude is equal to

). Each impulse

amplitude is equal to ![]() . (The amplitude of an impulse is its

algebraic area.) Similarly, since

. (The amplitude of an impulse is its

algebraic area.) Similarly, since

![]() , the spectrum of

, the spectrum of

![]() is an impulse of amplitude

is an impulse of amplitude ![]() at

at

![]() and amplitude

and amplitude ![]() at

at

![]() .

Multiplying

.

Multiplying ![]() by

by ![]() results in

results in

![]() which is shown in

the third plot, Fig.4.16c. Finally, adding together the first and

third plots, corresponding to

which is shown in

the third plot, Fig.4.16c. Finally, adding together the first and

third plots, corresponding to

![]() , we see that the

two positive-frequency impulses add in phase to give a unit

impulse (corresponding to

, we see that the

two positive-frequency impulses add in phase to give a unit

impulse (corresponding to

![]() ), and at frequency

), and at frequency

![]() , the two impulses, having opposite sign,

cancel in the sum, thus creating an analytic signal

, the two impulses, having opposite sign,

cancel in the sum, thus creating an analytic signal ![]() ,

as shown in Fig.4.16d. This sequence of operations illustrates

how the negative-frequency component

,

as shown in Fig.4.16d. This sequence of operations illustrates

how the negative-frequency component

![]() gets

filtered out by summing

gets

filtered out by summing

![]() with

with

![]() to produce the analytic signal

to produce the analytic signal

![]() corresponding

to the real signal

corresponding

to the real signal

![]() .

.

As a final example (and application), let

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is a slowly varying amplitude envelope (slow compared

with

is a slowly varying amplitude envelope (slow compared

with ![]() ). This is an example of amplitude modulation

applied to a sinusoid at ``carrier frequency''

). This is an example of amplitude modulation

applied to a sinusoid at ``carrier frequency'' ![]() (which is

where you tune your AM radio). The Hilbert transform is very close to

(which is

where you tune your AM radio). The Hilbert transform is very close to

![]() (if

(if ![]() were constant, this would

be exact), and the analytic signal is

were constant, this would

be exact), and the analytic signal is

![]() .

Note that AM demodulation4.14is now nothing more than the absolute value. I.e.,

.

Note that AM demodulation4.14is now nothing more than the absolute value. I.e.,

![]() . Due to this simplicity, Hilbert transforms are sometimes

used in making

amplitude envelope followers for narrowband signals (i.e., signals with all energy centered about a single ``carrier'' frequency).

AM demodulation is one application of a narrowband envelope follower.

. Due to this simplicity, Hilbert transforms are sometimes

used in making

amplitude envelope followers for narrowband signals (i.e., signals with all energy centered about a single ``carrier'' frequency).

AM demodulation is one application of a narrowband envelope follower.

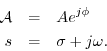

Generalized Complex Sinusoids

We have defined sinusoids and extended the definition to include complex sinusoids. We now extend one more step by allowing for exponential amplitude envelopes:

When ![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(t) &\isdef & {\cal A}e^{st} \\

&\isdef & A e^{j\phi} e^{(\...

... t} \left[\cos(\omega t + \phi) + j\sin(\omega t + \phi)\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img604.png)

Defining

![]() , we see that the generalized complex sinusoid

is just the complex sinusoid we had before with an exponential envelope:

, we see that the generalized complex sinusoid

is just the complex sinusoid we had before with an exponential envelope:

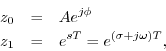

Sampled Sinusoids

In discrete-time audio processing, such as we normally do on a computer,

we work with samples of continuous-time signals. Let ![]() denote the sampling rate in Hz. For audio, we typically have

denote the sampling rate in Hz. For audio, we typically have ![]() kHz, since the audio band nominally extends to

kHz, since the audio band nominally extends to ![]() kHz. For compact

discs (CDs),

kHz. For compact

discs (CDs), ![]() kHz,

while for digital audio tape (DAT),

kHz,

while for digital audio tape (DAT), ![]() kHz.

kHz.

Let

![]() denote the sampling interval in seconds. Then to

convert from continuous to discrete time, we replace

denote the sampling interval in seconds. Then to

convert from continuous to discrete time, we replace ![]() by

by ![]() , where

, where ![]() is an integer interpreted as the sample number.

is an integer interpreted as the sample number.

The sampled generalized complex sinusoid is then

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(nT) &\isdef & \left.{\cal A}\,e^{st}\right\vert _{t=nT}\\

...

...

\left[\cos(\omega nT + \phi) + j\sin(\omega nT + \phi)\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img613.png)

Thus, the sampled case consists of a sampled complex sinusoid

multiplied by a sampled exponential envelope

![]() .

.

Powers of z

Choose any two complex numbers ![]() and

and ![]() , and form the sequence

, and form the sequence

What are the properties of this signal? Writing the complex numbers as

we see that the signal ![]() is always a discrete-time

generalized (exponentially enveloped) complex sinusoid:

is always a discrete-time

generalized (exponentially enveloped) complex sinusoid:

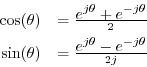

Figure 4.17 shows a plot of a generalized (exponentially

decaying, ![]() ) complex sinusoid versus time.

) complex sinusoid versus time.

Note that the left projection (onto the ![]() plane) is a decaying spiral,

the lower projection (real-part vs. time) is an exponentially decaying

cosine, and the upper projection (imaginary-part vs. time) is an

exponentially enveloped sine wave.

plane) is a decaying spiral,

the lower projection (real-part vs. time) is an exponentially decaying

cosine, and the upper projection (imaginary-part vs. time) is an

exponentially enveloped sine wave.

Phasor and Carrier Components of Sinusoids

If we restrict ![]() in Eq.

in Eq.![]() (4.10) to have unit modulus, then

(4.10) to have unit modulus, then

![]() and we obtain a discrete-time complex sinusoid.

and we obtain a discrete-time complex sinusoid.

where we have defined

Phasor

It is common terminology to callFor a real sinusoid,

When working with complex sinusoids, as in Eq.![]() (4.11), the phasor

representation

(4.11), the phasor

representation

![]() of a sinusoid can be thought of as simply the

complex amplitude of the sinusoid. I.e.,

it is the complex constant that multiplies the carrier term

of a sinusoid can be thought of as simply the

complex amplitude of the sinusoid. I.e.,

it is the complex constant that multiplies the carrier term

![]() .

.

Why Phasors are Important

Linear, time-invariant (LTI) systems can be said to perform only four operations on a signal: copying, scaling, delaying, and adding. As a result, each output is always a linear combination of delayed copies of the input signal(s). (A linear combination is simply a weighted sum, as discussed in §5.6.) In any linear combination of delayed copies of a complex sinusoid

![\begin{eqnarray*}

y(n) &=& \sum_{i=1}^N g_i e^{j[\omega (n-d_i)T]}

= \sum_{i=1}...

...e^{-j \omega d_i T}

= x(n) \sum_{i=1}^N g_i e^{-j \omega d_i T}

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img636.png)

The operation of the LTI system on a complex sinusoid is thus reduced to a calculation involving only phasors, which are simply complex numbers.

Since every signal can be expressed as a linear combination of complex sinusoids, this analysis can be applied to any signal by expanding the signal into its weighted sum of complex sinusoids (i.e., by expressing it as an inverse Fourier transform).

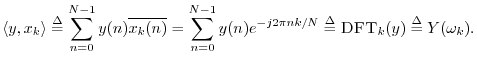

Importance of Generalized Complex Sinusoids

As a preview of things to come, note that one signal

![]() 4.15 is

projected onto another signal

4.15 is

projected onto another signal ![]() using an inner

product. The inner product

using an inner

product. The inner product

![]() computes the coefficient

of projection4.16 of

computes the coefficient

of projection4.16 of ![]() onto

onto ![]() . If

. If

![]() (a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

(a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

![]() . For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

. For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

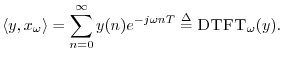

Another case of importance is the Discrete Time Fourier Transform

(DTFT), which is like the DFT except that the transform accepts an

infinite number of samples instead of only ![]() . In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

. In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

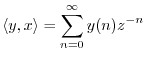

If, more generally,

![]() (a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

(a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

Why have a ![]() transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the

transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the ![]() transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the

transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the ![]() transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the

transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the ![]() transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in

transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in ![]() . As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the

. As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the ![]() plane. Similarly, the

plane. Similarly, the ![]() transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the

transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the ![]() plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the

plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the ![]() transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the

transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the ![]() transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the

transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the ![]() plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [68].

plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [68].

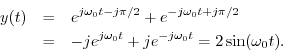

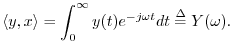

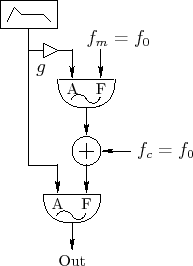

In the continuous-time case, we have the Fourier transform

which projects ![]() onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

![]() , and the appropriate inner product is

, and the appropriate inner product is

Finally, the Laplace transform is the continuous-time counterpart

of the ![]() transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids:

transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids:

Comparing Analog and Digital Complex Planes

In signal processing, it is customary to use ![]() as the Laplace transform

variable for continuous-time analysis, and

as the Laplace transform

variable for continuous-time analysis, and ![]() as the

as the ![]() -transform

variable for discrete-time analysis. In other words, for continuous-time

systems, the frequency domain is the ``

-transform

variable for discrete-time analysis. In other words, for continuous-time

systems, the frequency domain is the ``![]() plane'', while for discrete-time

systems, the frequency domain is the ``

plane'', while for discrete-time

systems, the frequency domain is the ``![]() plane.'' However, both are

simply complex planes.

plane.'' However, both are

simply complex planes.

Figure 4.18 illustrates the various sinusoids ![]() represented by points

in the

represented by points

in the ![]() plane. The frequency axis is

plane. The frequency axis is ![]() , called the

``

, called the

``![]() axis,'' and points along it correspond to complex sinusoids,

with dc at

axis,'' and points along it correspond to complex sinusoids,

with dc at ![]() (

(

![]() ).

The upper-half plane corresponds to positive

frequencies (counterclockwise circular or corkscrew motion) while the

lower-half plane corresponds to negative frequencies (clockwise motion).

In the left-half plane we have decaying (stable) exponential envelopes,

while in the right-half plane we have growing (unstable) exponential

envelopes. Along the real axis (

).

The upper-half plane corresponds to positive

frequencies (counterclockwise circular or corkscrew motion) while the

lower-half plane corresponds to negative frequencies (clockwise motion).

In the left-half plane we have decaying (stable) exponential envelopes,

while in the right-half plane we have growing (unstable) exponential

envelopes. Along the real axis (![]() ), we have pure exponentials.

Every point in the

), we have pure exponentials.

Every point in the ![]() plane corresponds to a generalized

complex sinusoid,

plane corresponds to a generalized

complex sinusoid,

![]() , with special cases including

complex sinusoids

, with special cases including

complex sinusoids

![]() , real exponentials

, real exponentials

![]() ,

and the constant function

,

and the constant function ![]() (dc).

(dc).

Figure 4.19 shows examples of various sinusoids

![]() represented by points in the

represented by points in the ![]() plane. The frequency axis is the ``unit

circle''

plane. The frequency axis is the ``unit

circle''

![]() , and points along it correspond to sampled

complex sinusoids, with dc at

, and points along it correspond to sampled

complex sinusoids, with dc at ![]() (

(

![]() ).

While the frequency axis is unbounded in the

).

While the frequency axis is unbounded in the ![]() plane, it is finite

(confined to the unit circle) in the

plane, it is finite

(confined to the unit circle) in the ![]() plane, which is natural because

the sampling rate is finite in the discrete-time case.

As in the

plane, which is natural because

the sampling rate is finite in the discrete-time case.

As in the

![]() plane, the upper-half plane corresponds to positive frequencies while

the lower-half plane corresponds to negative frequencies. Inside the unit

circle, we have decaying (stable) exponential envelopes, while outside the

unit circle, we have growing (unstable) exponential envelopes. Along the

positive real axis (

re

plane, the upper-half plane corresponds to positive frequencies while

the lower-half plane corresponds to negative frequencies. Inside the unit

circle, we have decaying (stable) exponential envelopes, while outside the

unit circle, we have growing (unstable) exponential envelopes. Along the

positive real axis (

re![]() im

im![]() ),

we have pure exponentials, but

along the negative real axis (

re

),

we have pure exponentials, but

along the negative real axis (

re![]() im

im![]() ), we have exponentially

enveloped sampled sinusoids at frequency

), we have exponentially

enveloped sampled sinusoids at frequency ![]() (exponentially enveloped

alternating sequences). The negative real axis in the

(exponentially enveloped

alternating sequences). The negative real axis in the ![]() plane is

normally a place where all signal

plane is

normally a place where all signal ![]() transforms should be zero, and all

system responses should be highly attenuated, since there should never be

any energy at exactly half the sampling rate (where amplitude and phase are

ambiguously linked). Every point in the

transforms should be zero, and all

system responses should be highly attenuated, since there should never be

any energy at exactly half the sampling rate (where amplitude and phase are

ambiguously linked). Every point in the ![]() plane can be said to

correspond to sampled generalized complex sinusoids of the form

plane can be said to

correspond to sampled generalized complex sinusoids of the form

![]() , with special cases being sampled complex

sinusoids

, with special cases being sampled complex

sinusoids

![]() , sampled real exponentials

, sampled real exponentials

![]() ,

and the constant sequence

,

and the constant sequence

![]() (dc).

(dc).

In summary, the exponentially enveloped (``generalized'') complex sinusoid

is the fundamental signal upon which other signals are ``projected'' in

order to compute a Laplace transform in the continuous-time case, or a ![]() transform in the discrete-time case. As a special case, if the exponential

envelope is eliminated (set to

transform in the discrete-time case. As a special case, if the exponential

envelope is eliminated (set to ![]() ), leaving only a complex sinusoid, then

the projection reduces to the Fourier transform in the continuous-time

case, and either the DFT (finite length) or DTFT (infinite length) in the

discrete-time case. Finally, there are still other variations, such as

short-time Fourier transforms (STFT) and wavelet transforms, which utilize

further modifications such as projecting onto windowed complex

sinusoids.

), leaving only a complex sinusoid, then

the projection reduces to the Fourier transform in the continuous-time

case, and either the DFT (finite length) or DTFT (infinite length) in the

discrete-time case. Finally, there are still other variations, such as

short-time Fourier transforms (STFT) and wavelet transforms, which utilize

further modifications such as projecting onto windowed complex

sinusoids.

Next Section:

Sinusoid Problems

Previous Section:

Exponentials

![\includegraphics[scale=0.8]{eps/circle}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img464.png)

![\includegraphics[width=3.5in]{eps/sineamtd}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img494.png)

![$\displaystyle x_m(t) \isdef \sin(\omega_m t)\sin(\omega_c t) = \frac{\cos[(\omega_m-\omega_c)t] - \cos[(\omega_m+\omega_c)t]}{2} \protect$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img505.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/bessel}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img537.png)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.8]{eps/circledecaying}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img620.png)

![\includegraphics[width=4.5in]{eps/splane}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img651.png)

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/zplane}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/mdft/img652.png)