Elementary Physics, Mechanics, and Acoustics

This appendix derives some basic results from the field of physics, particularly mechanics and acoustics, which are referenced elsewhere in this book, or which are known to be needed in practical synthesis models.

Newton's Laws of Motion

Perhaps the most heavily used equation in physics is Newton's second law of motion:

In this formulation, the applied force

Newton's Three Laws of Motion

Newton's three laws of motion may be stated as follows:

- Every object in a state of uniform motion will remain in that

state of motion unless an external force acts on it.

- Force equals mass times acceleration [

].

].

- For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

The first law, also called the law of inertia, was pioneered by Galileo. This was quite a conceptual leap because it was not possible in Galileo's time to observe a moving object without at least some frictional forces dragging against the motion. In fact, for over a thousand years before Galileo, educated individuals believed Aristotle's formulation that, wherever there is motion, there is an external force producing that motion.

The second law,

![]() , actually implies the first law, since

when

, actually implies the first law, since

when ![]() (no applied force), the acceleration

(no applied force), the acceleration ![]() is zero,

implying a constant velocity

is zero,

implying a constant velocity ![]() . (The velocity is simply the

integral with respect to time of

. (The velocity is simply the

integral with respect to time of

![]() .)

.)

Newton's third law implies conservation of momentum [137]. It can also be seen as following from the second law: When one object ``pushes'' a second object at some (massless) point of contact using an applied force, there must be an equal and opposite force from the second object that cancels the applied force. Otherwise, there would be a nonzero net force on a massless point which, by the second law, would accelerate the point of contact by an infinite amount.

In summary, Newton's laws boil down to ![]() . An enormous quantity

of physical science has been developed by applying this

simpleB.1 mathematical law to different physical

situations.

. An enormous quantity

of physical science has been developed by applying this

simpleB.1 mathematical law to different physical

situations.

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of matter.

From Newton's second law,

![]() , we have that the amount of

force required to accelerate an object, by a given amount, is

proportional to its mass. Thus, the mass of an object quantifies its

inertia--its resistance to a change in velocity.

, we have that the amount of

force required to accelerate an object, by a given amount, is

proportional to its mass. Thus, the mass of an object quantifies its

inertia--its resistance to a change in velocity.

We can measure the mass of an object by measuring the

gravitational force between it and another known mass,

as described in the next section. This is a special case of measuring

its acceleration in response to a known force. Whatever the force ![]() ,

the mass

,

the mass ![]() is given by

is given by ![]() divided by the resulting acceleration

divided by the resulting acceleration

![]() , again by Newton's second law

, again by Newton's second law ![]() .

.

The usual mathematical model for an ideal mass is a dimensionless point at some location in space. While no real objects are dimensionless, they can often be treated mathematically as dimensionless points located at their center of mass, or centroid (§B.4.1).

The physical state of a mass ![]() at time

at time ![]() consists of its

position

consists of its

position ![]() and velocity

and velocity

![]() in 3D space.

The amount of mass itself,

in 3D space.

The amount of mass itself, ![]() , is regarded as a fixed parameter that

does not change. In other words, the state

, is regarded as a fixed parameter that

does not change. In other words, the state

![]() of a

physical system typically changes over time, while any

parameters of the system, such as mass

of a

physical system typically changes over time, while any

parameters of the system, such as mass ![]() , remain fixed over

time (unless otherwise specified).

, remain fixed over

time (unless otherwise specified).

Gravitational Force

We are all familiar with the force of gravity. It is a

fundamental observed property of our universe that any two masses

![]() and

and ![]() experience an attracting force

experience an attracting force ![]() given by the

formula

given by the

formula

where

The law of gravitation Eq.![]() (B.2) can be accepted as an

experimental fact which defines the concept of a force.B.3 The giant conceptual leap taken by Newton was that the law of

gravitation is

universal--applying to celestial bodies as well as objects on

earth. When a mass is ``dropped'' and allowed to ``fall'' in a

gravitational field, it is observed to experience a

uniform acceleration proportional to its mass. Newton's second

law of motion (§B.1) quantifies this result.

(B.2) can be accepted as an

experimental fact which defines the concept of a force.B.3 The giant conceptual leap taken by Newton was that the law of

gravitation is

universal--applying to celestial bodies as well as objects on

earth. When a mass is ``dropped'' and allowed to ``fall'' in a

gravitational field, it is observed to experience a

uniform acceleration proportional to its mass. Newton's second

law of motion (§B.1) quantifies this result.

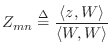

Hooke's Law

Consider an ideal spring suspending a mass from a rigid ceiling, as

depicted in Fig.B.1. Assume the mass is at rest,

and that its distance ![]() from the ceiling is fixed.

from the ceiling is fixed.

If ![]() denotes the mass of the earth, and

denotes the mass of the earth, and ![]() is the distance of mass

is the distance of mass

![]() 's center from the earth's center of mass, then the downward force

on the mass

's center from the earth's center of mass, then the downward force

on the mass ![]() is given by Eq.

is given by Eq.![]() (B.2) as

(B.2) as

where

Note that the force on the spring in Fig.B.1 is gravitational force. Equal and opposite to the force of gravity is the spring force exerted upward by the spring on the mass (which is not moving). We know that the spring force is equal and opposite to the gravitational force because the mass would otherwise be accelerated by the net force.B.4 Therefore, like gravity, a displaced spring can be regarded as a definition of an applied force. That is, whenever you have to think of an applied force, you can always consider it as being delivered by the end of some ideal spring attached to some external physical system.

Note, by the way, that normal interaction forces when objects touch arise from the Coulomb force (electrostatic force, or repulsion of like charges) between electron orbitals. This electrostatic force obeys an ``inverse square law'' like gravity, and therefore also behaves like an ideal spring for small displacements.B.5

The specific value of ![]() depends on the physical units adopted as

well as the ``stiffness'' of the spring. What is most important in

this definition of force is that a doubling of spring displacement

doubles the force. That is, the spring force is a linear

function of spring displacement (compression or stretching).

depends on the physical units adopted as

well as the ``stiffness'' of the spring. What is most important in

this definition of force is that a doubling of spring displacement

doubles the force. That is, the spring force is a linear

function of spring displacement (compression or stretching).

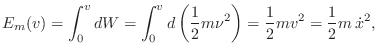

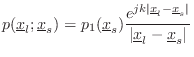

Applying Newton's Laws of Motion

As a simple example, consider a mass ![]() driven along a frictionless

surface by an ideal spring

driven along a frictionless

surface by an ideal spring ![]() , as shown in Fig.B.2.

Assume that the mass position

, as shown in Fig.B.2.

Assume that the mass position ![]() corresponds to the spring at rest,

i.e., not stretched or compressed. The force necessary to compress the

spring by a distance

corresponds to the spring at rest,

i.e., not stretched or compressed. The force necessary to compress the

spring by a distance ![]() is given by Hooke's law (§B.1.3):

is given by Hooke's law (§B.1.3):

where we have defined

where

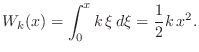

Work = Force times Distance = Energy

Work is defined as force times distance. Work is a measure of the energy expended in applying a force to move an object.B.8

The work required to compress a spring ![]() through a displacement of

through a displacement of ![]() meters, starting from rest, is then

meters, starting from rest, is then

Work can also be negative. For example, when uncompressing an ideal spring, the (positive) work done by the spring on its moving end support can be interpreted also as saying that the end support performs negative work on the spring as it allows the spring to uncompress. When negative work is performed, the driving system is always accepting energy from the driven system. This is all simply accounting. Physically, one normally considers the driver as the agent performing the positive work, i.e., the one expending energy to move the driven object. Thus, when allowing a spring to uncompress, we consider the spring as performing (positive) work on whatever is attached to its moving end.

During a sinusoidal mass-spring oscillation, as derived in §B.1.4, each period of the oscillation can be divided into equal sections during which either the mass performs work on the spring, or vice versa.

Gravity, spring forces, and electrostatic forces are examples of

conservative forces. Conservative forces have the property

that the work required to move an object from point ![]() to point

to point ![]() ,

either with or against the force, depends only on the locations of

points

,

either with or against the force, depends only on the locations of

points ![]() and

and ![]() in space, not on the path taken from

in space, not on the path taken from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Potential Energy in a Spring

When compressing an ideal spring, work is performed, and this

work is stored in the spring in the form of what we call

potential energy. Equation (B.6) above gives the quantitative

formula for the potential energy ![]() stored in an ideal spring

after it has been compressed

stored in an ideal spring

after it has been compressed ![]() meters from rest.

meters from rest.

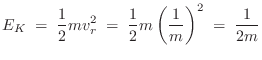

Kinetic Energy of a Mass

Kinetic energy is energy associated with motion. For example, when a spring uncompresses and accelerates a mass, as in the configuration of Fig.B.2, work is performed on the mass by the spring, and we say that the potential energy of the spring is converted to kinetic energy of the mass.

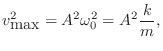

Suppose in Fig.B.2 we have an initial spring compression

by ![]() meters at time

meters at time ![]() , and the mass velocity is zero at

, and the mass velocity is zero at

![]() . Then from the equation of motion Eq.

. Then from the equation of motion Eq.![]() (B.5), we can calculate

when the spring returns to rest (

(B.5), we can calculate

when the spring returns to rest (![]() ). This first happens at the

first zero of

). This first happens at the

first zero of

![]() , which is time

, which is time

![]() . At this time, the velocity,

given by the time-derivative of Eq.

. At this time, the velocity,

given by the time-derivative of Eq.![]() (B.5),

(B.5),

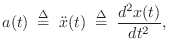

Mass Kinetic Energy from Virtual Work

From Newton's second law,

![]() (introduced in Eq.

(introduced in Eq.![]() (B.1)),

we can use d'Alembert's idea of virtual work to derive the

formula for the kinetic energy of a mass given its speed

(B.1)),

we can use d'Alembert's idea of virtual work to derive the

formula for the kinetic energy of a mass given its speed

![]() .

Let

.

Let ![]() denote a small (infinitesimal) displacement of the mass in

the

denote a small (infinitesimal) displacement of the mass in

the ![]() direction. Then we have, using the calculus of differentials,

direction. Then we have, using the calculus of differentials,

Thus, by Newton's second law, a differential of work ![]() applied to a

mass

applied to a

mass ![]() by force

by force ![]() through distance

through distance ![]() boosts the kinetic energy

of the mass by

boosts the kinetic energy

of the mass by

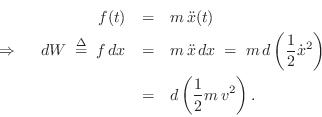

![]() . The kinetic energy of a mass moving at

speed

. The kinetic energy of a mass moving at

speed ![]() is then given by the integral of all such differential

boosts from 0 to

is then given by the integral of all such differential

boosts from 0 to ![]() :

:

The quantity ![]() is classically called the virtual work

associated with force

is classically called the virtual work

associated with force ![]() , and

, and ![]() a virtual displacement

[544].

a virtual displacement

[544].

Energy in the Mass-Spring Oscillator

Summarizing the previous sections, we say that a compressed spring holds a potential energy equal to the work required to compress the spring from rest to its current displacement. If a compressed spring is allowed to expand by pushing a mass, as in the system of Fig.B.2, the potential energy in the spring is converted to kinetic energy in the moving mass.

We can draw some inferences from the oscillatory motion of the

mass-spring system written in Eq.![]() (B.5):

(B.5):

- From a global point of view, we see that energy is conserved, since the oscillation never decays.

- At the peaks of the displacement

(when

(when

is either

is either

or

or  ), all energy is in the form of potential energy,

i.e., the spring is either maximally compressed or stretched, and the mass

is momentarily stopped as it is changing direction.

), all energy is in the form of potential energy,

i.e., the spring is either maximally compressed or stretched, and the mass

is momentarily stopped as it is changing direction.

- At the zero-crossings of

, the spring is momentarily

relaxed, thereby holding no potential energy; at these instants, all

energy is in the form of kinetic energy, stored in the motion of the mass.

, the spring is momentarily

relaxed, thereby holding no potential energy; at these instants, all

energy is in the form of kinetic energy, stored in the motion of the mass.

- Since total energy is conserved (§B.2.5), the kinetic

energy of the mass at the displacement zero-crossings is exactly the

amount needed to stretch the spring to displacement

(or compress

it to

(or compress

it to  ) before the mass stops and changes direction. At all

times, the total energy

) before the mass stops and changes direction. At all

times, the total energy  is equal to the sum of the potential

energy

is equal to the sum of the potential

energy  stored in the spring, and the kinetic energy

stored in the spring, and the kinetic energy  stored in the mass:

stored in the mass:

![$\displaystyle \mbox{constant [$E_k(0)$]}$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2672.png)

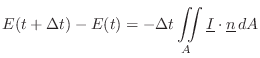

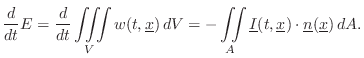

Energy Conservation

It is a remarkable property of our universe that energy is conserved under all circumstances. There are no known exceptions to the conservation of energy, even when relativistic and quantum effects are considered.B.9

Energy may be defined as the ability to do work, where work may be defined as force times distance (§B.2).

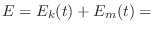

Energy Conservation in the Mass-Spring System

Recall that Newton's second law applied to a mass-spring system, as in §B.1.4, yields

![\begin{eqnarray*}

0

&=& m{\ddot x}(t){\dot x}(t) + k\,x(t){\dot x}(t)\\

&=& m\...

...{d}{dt} \left[ E_m(t) + E_k(t) \right]\\

&=& \frac{d}{dt} E(t).

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2682.png)

Thus, Newton's second law and Hooke's law imply conservation of energy in the mass-spring system of Fig.B.2.

Momentum

The momentum of a mass ![]() is usually defined by

is usually defined by

Conservation of Momentum

Like energy, momentum is conserved in physical systems. For example, when two masses collide and recoil from each other, the total momentum after the collision equals that before the collision. Since the momentum is a three-dimensional vector in Euclidean space, momentum conservation provides three simultaneous equations, in general.B.10

Rigid-Body Dynamics

Below are selected topics from rigid-body dynamics, a subtopic of classical mechanics involving the use of Newton's laws of motion to solve for the motion of rigid bodies moving in 1D, 2D, or 3D space.B.11 We may think of a rigid body as a distributed mass, that is, a mass that has length, area, and/or volume rather than occupying only a single point in space. Rigid body models have application in stiff strings (modeling them as disks of mass interconnect by ideal springs), rigid bridges, resonator braces, and so on.

We have already used Newton's ![]() to formulate mathematical dynamic

models for the ideal point-mass (§B.1.1), spring

(§B.1.3), and a simple mass-spring system (§B.1.4).

Since many physical systems can be modeled as assemblies of masses and

(normally damped) springs, we are pretty far along already. However,

when the springs interconnecting our point-masses are very stiff, we

may approximate them as rigid to simplify our simulations. Thus,

rigid bodies can be considered mass-spring systems in which the

springs are so stiff that they can be treated as rigid massless rods

(infinite spring-constants

to formulate mathematical dynamic

models for the ideal point-mass (§B.1.1), spring

(§B.1.3), and a simple mass-spring system (§B.1.4).

Since many physical systems can be modeled as assemblies of masses and

(normally damped) springs, we are pretty far along already. However,

when the springs interconnecting our point-masses are very stiff, we

may approximate them as rigid to simplify our simulations. Thus,

rigid bodies can be considered mass-spring systems in which the

springs are so stiff that they can be treated as rigid massless rods

(infinite spring-constants ![]() , in the notation of §B.1.3).

, in the notation of §B.1.3).

So, what is new about distributed masses, as opposed to the point-masses considered previously? As we will see, the main new ingredient is rotational dynamics. The total momentum of a rigid body (distributed mass) moving through space will be described as the sum of the linear momentum of its center of mass (§B.4.1 below) plus the angular momentum about its center of mass (§B.4.13 below).

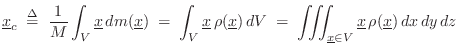

Center of Mass

The center of mass (or centroid) of a rigid body is

found by averaging the spatial points of the body

![]() weighted by the mass

weighted by the mass ![]() of those points:B.12

of those points:B.12

A nice property of the center of mass is that gravity acts on a far-away object as if all its mass were concentrated at its center of mass. For this reason, the center of mass is often called the center of gravity.

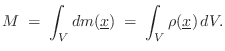

Linear Momentum of the Center of Mass

Consider a system of ![]() point-masses

point-masses ![]() , each traveling with

vector velocity

, each traveling with

vector velocity

![]() , and not necessarily rigidly attached to

each other. Then the total momentum of the system is

, and not necessarily rigidly attached to

each other. Then the total momentum of the system is

Thus, the momentum

![]() of any collection of masses

of any collection of masses ![]() (including rigid bodies) equals the total mass

(including rigid bodies) equals the total mass ![]() times the

velocity of the center-of-mass.

times the

velocity of the center-of-mass.

Whoops, No Angular Momentum!

The previous result might be surprising since we said at the outset that we were going to decompose the total momentum into a sum of linear plus angular momentum. Instead, we found that the total momentum is simply that of the center of mass, which means any angular momentum that might have been present just went away. (The center of mass is just a point that cannot rotate in a measurable way.) Angular momentum does not contribute to linear momentum, so it provides three new ``degrees of freedom'' (three new energy storage dimensions, in 3D space) that are ``missed'' when considering only linear momentum.

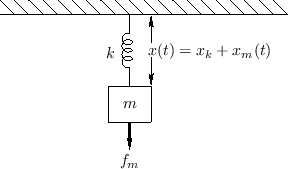

To obtain the desired decomposition of momentum into linear plus angular momentum, we will choose a fixed reference point in space (usually the center of mass) and then, with respect to that reference point, decompose an arbitrary mass-particle travel direction into the sum of two mutually orthogonal vector components: one will be the vector component pointing radially with respect to the fixed point (for the ``linear momentum'' component), and the other will be the vector component pointing tangentially with respect to the fixed point (for the ``angular momentum''), as shown in Fig.B.3. When the reference point is the center of mass, the resultant radial force component gives us the force on the center of mass, which creates linear momentum, while the net tangential component (times distance from the center-of-mass) give us a resultant torque about the reference point, which creates angular momentum. As we saw above, because the tangential force component does not contribute to linear momentum, we can simply sum the external force vectors and get the same result as summing their radial components. These topics will be discussed further below, after some elementary preliminaries.

![\includegraphics[width=1.5in]{eps/rigidbody}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2710.png) |

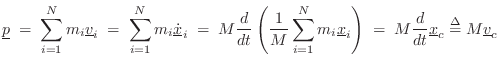

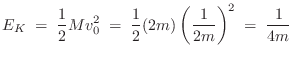

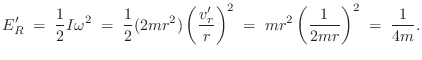

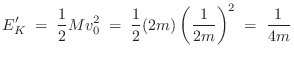

Translational Kinetic Energy

The translational kinetic energy of a collection of masses

![]() is given by

is given by

More generally, the total energy of a collection of masses (including distributed and/or rigidly interconnected point-masses) can be expressed as the sum of the translational and rotational kinetic energies [270, p. 98].

Rotational Kinetic Energy

![\includegraphics[width=1.2in]{eps/masscircle}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2715.png) |

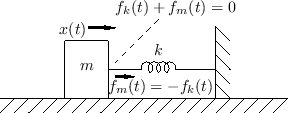

The rotational kinetic energy of a rigid assembly of masses (or

mass distribution) is the sum of the rotational kinetic energies of

the component masses. Therefore, consider a point-mass ![]() rotatingB.13 in a circular orbit

of radius

rotatingB.13 in a circular orbit

of radius ![]() and angular velocity

and angular velocity ![]() (radians per second), as

shown in Fig.B.4. To make it a closed system, we can

imagine an effectively infinite mass at the origin

(radians per second), as

shown in Fig.B.4. To make it a closed system, we can

imagine an effectively infinite mass at the origin

![]() . Then the

speed of the mass along the circle is

. Then the

speed of the mass along the circle is ![]() , and its kinetic

energy is

, and its kinetic

energy is

![]() . Since this is what we want

for the rotational kinetic energy of the system, it is

convenient to define it in terms of angular velocity

. Since this is what we want

for the rotational kinetic energy of the system, it is

convenient to define it in terms of angular velocity ![]() in

radians per second. Thus, we write

in

radians per second. Thus, we write

where

is called the mass moment of inertia.

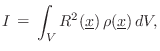

Mass Moment of Inertia

The mass moment of inertia ![]() (or simply moment of

inertia), plays the role of mass in rotational dynamics, as

we saw in

Eq.

(or simply moment of

inertia), plays the role of mass in rotational dynamics, as

we saw in

Eq.![]() (B.7) above.

(B.7) above.

The mass moment of inertia of a rigid body, relative to a given axis of rotation, is given by a weighted sum over its mass, with each mass-point weighted by the square of its distance from the rotation axis. Compare this with the center of mass (§B.4.1) in which each mass-point is weighted by its vector location in space (and divided by the total mass).

Equation (B.8) above gives the moment of inertia for a single point-mass

![]() rotating a distance

rotating a distance ![]() from the axis to be

from the axis to be ![]() . Therefore,

for a rigid collection of point-masses

. Therefore,

for a rigid collection of point-masses ![]() ,

,

![]() ,B.14 the

moment of inertia about a given axis of rotation is obtained by adding

the component moments of inertia:

,B.14 the

moment of inertia about a given axis of rotation is obtained by adding

the component moments of inertia:

where

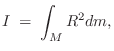

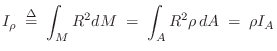

For a continuous mass distribution, the moment of inertia is given by integrating the contribution of each differential mass element:

|

(B.10) |

where

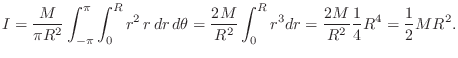

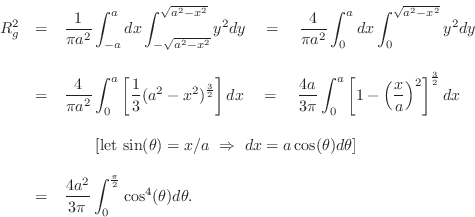

Circular Disk Rotating in Its Own Plane

For example, the moment of inertia for a uniform circular disk of

total mass ![]() and radius

and radius ![]() , rotating in its own plane about a

rotation axis piercing its center, is given by

, rotating in its own plane about a

rotation axis piercing its center, is given by

Circular Disk Rotating About Its Diameter

The moment of inertia for the same circular disk rotating about an axis in the plane of the disk, passing through its center, is given by

![$\displaystyle I = \frac{M}{\pi R^2}\cdot 4\int_0^{\pi/2} \int_0^R [r\cos(\theta)]^2\, r\,dr\,d\theta

= \frac{1}{4}MR^2

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2728.png)

Perpendicular Axis Theorem

In general, for any 2D distribution of mass, the moment of inertia

about an axis orthogonal to the plane of the mass equals the sum of

the moments of inertia about any two mutually orthogonal axes in the

plane of the mass intersecting the first axis. To see this, consider

an arbitrary mass element ![]() having rectilinear coordinates

having rectilinear coordinates

![]() in the plane of the mass. (All three coordinate axes

intersect at a point in the mass-distribution plane.) Then its moment

of inertia about the axis orthogonal to the mass plane is

in the plane of the mass. (All three coordinate axes

intersect at a point in the mass-distribution plane.) Then its moment

of inertia about the axis orthogonal to the mass plane is

![]() while its moment of inertia about coordinate axes

within the mass-plane are respectively

while its moment of inertia about coordinate axes

within the mass-plane are respectively ![]() and

and ![]() .

This, the perpendicular axis theorem is an immediate consequence of

the Pythagorean theorem for right triangles.

.

This, the perpendicular axis theorem is an immediate consequence of

the Pythagorean theorem for right triangles.

Parallel Axis Theorem

Let ![]() denote the moment of inertia for a rotation axis passing

through the center of mass, and let

denote the moment of inertia for a rotation axis passing

through the center of mass, and let ![]() denote

the moment of inertia for a rotation axis parallel to the first

but a distance

denote

the moment of inertia for a rotation axis parallel to the first

but a distance ![]() away from it. Then the parallel axis theorem

says that

away from it. Then the parallel axis theorem

says that

Stretch Rule

Note that the moment of inertia does not change when masses are moved

along a vector parallel to the axis of rotation (see, e.g.,

Eq.![]() (B.9)). Thus, any rigid body may be ``stretched'' or

``squeezed'' parallel to the rotation axis without changing its moment

of inertia. This is known as the stretch rule, and it can be

used to simplify geometry when finding the moment of inertia.

(B.9)). Thus, any rigid body may be ``stretched'' or

``squeezed'' parallel to the rotation axis without changing its moment

of inertia. This is known as the stretch rule, and it can be

used to simplify geometry when finding the moment of inertia.

For example, we saw in §B.4.4 that the moment of inertia

of a point-mass ![]() a distance

a distance ![]() from the axis of rotation is given

by

from the axis of rotation is given

by ![]() . By the stretch rule, the same applies to an ideal

rod of mass

. By the stretch rule, the same applies to an ideal

rod of mass ![]() parallel to and distance

parallel to and distance ![]() from the axis of

rotation.

from the axis of

rotation.

Note that mass can be also be ``stretched'' along the circle of

rotation without changing the moment of inertia for the mass about

that axis. Thus, the point mass ![]() can be stretched out to form a

mass ring at radius

can be stretched out to form a

mass ring at radius ![]() about the axis of rotation without

changing its moment of inertia about that axis. Similarly, the ideal

rod of the previous paragraph can be stretched tangentially to form a

cylinder of radius

about the axis of rotation without

changing its moment of inertia about that axis. Similarly, the ideal

rod of the previous paragraph can be stretched tangentially to form a

cylinder of radius ![]() and mass

and mass ![]() , with its axis of symmetry

coincident with the axis of rotation. In all of these examples, the

moment of inertia is

, with its axis of symmetry

coincident with the axis of rotation. In all of these examples, the

moment of inertia is ![]() about the axis of rotation.

about the axis of rotation.

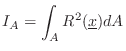

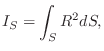

Area Moment of Inertia

The area moment of inertia is the second moment of an area ![]() around a given axis:

around a given axis:

Comparing with the definition of mass moment of inertia in §B.4.4 above, we see that mass is replaced by area in the area moment of inertia.

In a planar mass distribution with total mass ![]() uniformly

distributed over an area

uniformly

distributed over an area ![]() (i.e., a constant mass density of

(i.e., a constant mass density of

![]() ), the mass moment of inertia

), the mass moment of inertia ![]() is given by the area

moment of inertia

is given by the area

moment of inertia ![]() times mass-density

times mass-density ![]() :

:

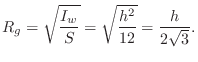

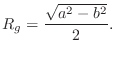

Radius of Gyration

For a planar distribution of mass rotating about some axis in the plane of the mass, the radius of gyration is the distance from the axis that all mass can be concentrated to obtain the same mass moment of inertia. Thus, the radius of gyration is the ``equivalent distance'' of the mass from the axis of rotation. In this context, gyration can be defined as rotation of a planar region about some axis lying in the plane.

For a bar cross-section with area ![]() , the radius of gyration is given by

, the radius of gyration is given by

where

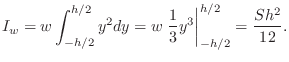

Rectangular Cross-Section

For a rectangular cross-section of height ![]() and width

and width ![]() , area

, area

![]() , the area moment of inertia about the horizontal midline is

given by

, the area moment of inertia about the horizontal midline is

given by

The radius of gyration can be thought of as the ``effective radius'' of the mass distribution with respect to its inertial response to rotation (``gyration'') about the chosen axis.

Most cross-sectional shapes (e.g., rectangular), have at least two radii of gyration. A circular cross-section has only one, and its radius of gyration is equal to half its radius, as shown in the next section.

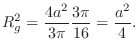

Circular Cross-Section

For a circular cross-section of radius ![]() , Eq.

, Eq.![]() (B.11) tells us

that the squared radius of gyration about any line passing through the

center of the cross-section is given by

(B.11) tells us

that the squared radius of gyration about any line passing through the

center of the cross-section is given by

Using the elementrary trig identity

![]() , we readily

derive

, we readily

derive

For a circular tube in which the mass of the cross-section lies

within a circular annulus having inner radius ![]() and outer

radius

and outer

radius ![]() , the radius of gyration is given by

, the radius of gyration is given by

Two Masses Connected by a Rod

As an introduction to the decomposition of rigid-body motion into

translational and rotational components, consider the

simple system shown in Fig.B.5. The excitation force

densityB.15 ![]() can be

applied anywhere between

can be

applied anywhere between ![]() and

and ![]() along the connecting rod.

We will deliver a vertical impulse of momentum to the mass on the

right, and show, among other observations, that the total kinetic

energy is split equally into (1) the rotational kinetic energy

about the center of mass, and (2) the translational kinetic

energy of the total mass, treated as being located at the center of

mass. This is accomplished by defining a new frame of

reference (i.e., a moving coordinate system) that has its origin at

the center of mass.

along the connecting rod.

We will deliver a vertical impulse of momentum to the mass on the

right, and show, among other observations, that the total kinetic

energy is split equally into (1) the rotational kinetic energy

about the center of mass, and (2) the translational kinetic

energy of the total mass, treated as being located at the center of

mass. This is accomplished by defining a new frame of

reference (i.e., a moving coordinate system) that has its origin at

the center of mass.

First, note that the driving-point impedance (§7.1)

``seen'' by the driving force ![]() varies as a function of

varies as a function of ![]() .

At

.

At ![]() , The excitation

, The excitation ![]() sees a ``point mass''

sees a ``point mass'' ![]() , and no

rotation is excited by the force (by symmetry). At

, and no

rotation is excited by the force (by symmetry). At ![]() , on the

other hand, the excitation

, on the

other hand, the excitation

![]() only sees mass

only sees mass ![]() at time

0, because the vertical motion of either point-mass initially only

rotates the other point-mass via the massless connecting rod. Thus,

an observation we can make right away is that the driving point

impedance seen by

at time

0, because the vertical motion of either point-mass initially only

rotates the other point-mass via the massless connecting rod. Thus,

an observation we can make right away is that the driving point

impedance seen by ![]() depends on the striking point

depends on the striking point ![]() and,

away from

and,

away from ![]() , it depends on time

, it depends on time ![]() as well.

as well.

To avoid dealing with a time-varying driving-point impedance, we will

use an impulsive force input at time ![]() . Since momentum is the

time-integral of force (

. Since momentum is the

time-integral of force (

![]() ), our

excitation will be a unit momentum transferred to the two-mass

system at time 0.

), our

excitation will be a unit momentum transferred to the two-mass

system at time 0.

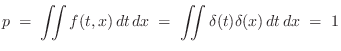

Striking the Rod in the Middle

First, consider

![]() . That is, we apply an

upward unit-force impulse at time 0 in the middle of the rod. The

total momentum delivered in the neighborhood of

. That is, we apply an

upward unit-force impulse at time 0 in the middle of the rod. The

total momentum delivered in the neighborhood of ![]() and

and ![]() is

obtained by integrating the applied force density with respect to time

and position:

is

obtained by integrating the applied force density with respect to time

and position:

The kinetic energy of the system after time zero is

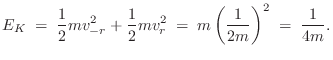

Striking One of the Masses

Now let

![]() . That is, we apply an impulse

of vertical momentum to the mass on the right at time 0.

. That is, we apply an impulse

of vertical momentum to the mass on the right at time 0.

In this case, the unit of vertical momentum is transferred entirely to the mass on the right, so that

Note that the velocity of the center-of-mass ![]() is the

same as it was when we hit the midpoint of the rod. This is an

important general equivalence: The sum of all external force vectors

acting on a rigid body can be applied as a single resultant force

vector to the total mass concentrated at the center of mass to find

the linear (translational) motion produced. (Recall from §B.4.1

that such a sum is the same as the sum of all radially acting external

force components, since the tangential components contribute only to

rotation and not to translation.)

is the

same as it was when we hit the midpoint of the rod. This is an

important general equivalence: The sum of all external force vectors

acting on a rigid body can be applied as a single resultant force

vector to the total mass concentrated at the center of mass to find

the linear (translational) motion produced. (Recall from §B.4.1

that such a sum is the same as the sum of all radially acting external

force components, since the tangential components contribute only to

rotation and not to translation.)

All of the kinetic energy is in the mass on the right just after time zero:

However, after time zero, things get more complicated, because the mass on the left gets dragged into a rotation about the center of mass.

To simplify ongoing analysis, we can define a body-fixed frame

of referenceB.16 having its origin at the center of mass. Let ![]() denote a velocity in this frame. Since the velocity of the center of

mass is

denote a velocity in this frame. Since the velocity of the center of

mass is

![]() , we can convert any velocity

, we can convert any velocity ![]() in the

body-fixed frame to a velocity

in the

body-fixed frame to a velocity ![]() in the original frame by adding

in the original frame by adding

![]() to it, viz.,

to it, viz.,

In the body-fixed frame, all kinetic energy is rotational about

the origin. Recall (Eq.![]() (B.9)) that the moment of inertia for this

system, with respect to the center of mass at

(B.9)) that the moment of inertia for this

system, with respect to the center of mass at ![]() , is

, is

In summary, we defined a moving body-fixed frame having its origin at the center-of-mass, and the total kinetic energy was computed to be

It is important to note that, after time zero, both the linear

momentum of the center-of-mass (

![]() ), and the angular momentum in the body-fixed frame

(

), and the angular momentum in the body-fixed frame

(

![]() ) remain

constant over time.B.17 In the original space-fixed

frame, on the other hand, there is a complex transfer of momentum back

and forth between the masses after time zero.

) remain

constant over time.B.17 In the original space-fixed

frame, on the other hand, there is a complex transfer of momentum back

and forth between the masses after time zero.

Similarly, the translational kinetic energy of the total mass, treated as being concentrated at its center-of-mass, and the rotational kinetic energy in the body-fixed frame, are both constant after time zero, while in the space-fixed frame, kinetic energy transfers back and forth between the two masses. At all times, however, the total kinetic energy is the same in both formulations.

Angular Velocity Vector

When working with rotations, it is convenient to define the

angular-velocity vector as a vector

![]() pointing

along the axis of rotation. There are two directions we could

choose from, so we pick the one corresponding to the right-hand

rule, i.e., when the fingers of the right hand curl in the direction

of the rotation, the thumb points in the direction of the angular

velocity vector.B.18 The

length

pointing

along the axis of rotation. There are two directions we could

choose from, so we pick the one corresponding to the right-hand

rule, i.e., when the fingers of the right hand curl in the direction

of the rotation, the thumb points in the direction of the angular

velocity vector.B.18 The

length

![]() should obviously equal the angular

velocity

should obviously equal the angular

velocity ![]() . It is convenient also to work with a unit-length

variant

. It is convenient also to work with a unit-length

variant

![]() .

.

As introduced in Eq.![]() (B.8) above, the mass moment of inertia is

given by

(B.8) above, the mass moment of inertia is

given by ![]() where

where ![]() is the distance from the (instantaneous)

axis of rotation to the mass

is the distance from the (instantaneous)

axis of rotation to the mass ![]() located at

located at

![]() . In

terms of the angular-velocity vector

. In

terms of the angular-velocity vector

![]() , we can write this as

(see Fig.B.6)

, we can write this as

(see Fig.B.6)

where

![\includegraphics[width=1.5in]{eps/pxov}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2806.png) |

Using the vector cross product (defined in the next section),

we will show (in §B.4.17) that ![]() can be written more succinctly as

can be written more succinctly as

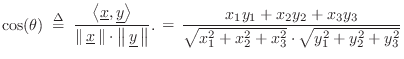

Vector Cross Product

The vector cross product (or simply vector product, as

opposed to the scalar product (which is also called the

dot product, or inner product)) is commonly used in

vector calculus--a basic mathematical toolset used in

mechanics [270,258],

acoustics [349], electromagnetism [356], quantum

mechanics, and more. It can be defined symbolically in the form of

a matrix determinant:B.19

where

The second and third lines of Eq.![]() (B.15) make it clear that

(B.15) make it clear that

![]() . This is one example of a host of identities that

one learns in vector calculus and its applications.

. This is one example of a host of identities that

one learns in vector calculus and its applications.

Cross-Product Magnitude

It is a straightforward exercise to show that the cross-product magnitude is equal to the product of the vector lengths times the sine of the angle between them:B.21

where

To derive Eq.![]() (B.16), let's begin with the cross-product in matrix

form as

(B.16), let's begin with the cross-product in matrix

form as

![]() using the first matrix form in the

third line of the cross-product definition in Eq.

using the first matrix form in the

third line of the cross-product definition in Eq.![]() (B.15) above. Then

(B.15) above. Then

where

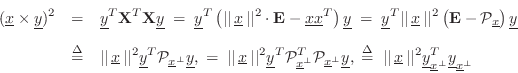

![]() denotes the identity matrix in

denotes the identity matrix in

![]() ,

,

![]() denotes the orthogonal-projection matrix onto

denotes the orthogonal-projection matrix onto

![]() [451],

[451],

![]() denotes the projection matrix onto

the orthogonal complement of

denotes the projection matrix onto

the orthogonal complement of

![]() ,

,

![]() denotes the component of

denotes the component of

![]() orthogonal to

orthogonal to

![]() , and we used the fact that orthogonal projection matrices

, and we used the fact that orthogonal projection matrices

![]() are idempotent (i.e.,

are idempotent (i.e.,

![]() ) and

symmetric (when real, as we have here) when we replaced

) and

symmetric (when real, as we have here) when we replaced

![]() by

by

![]() above. Finally,

note that the length of

above. Finally,

note that the length of

![]() is

is

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the angle

between the 1D subspaces spanned by

is the angle

between the 1D subspaces spanned by

![]() and

and

![]() in the plane

including both vectors. Thus,

in the plane

including both vectors. Thus,

The direction of the cross-product vector is then taken to be

orthogonal to both

![]() and

and

![]() according to the right-hand

rule. This orthogonality can be checked by verifying that

according to the right-hand

rule. This orthogonality can be checked by verifying that

![]() . The right-hand-rule parity can be checked by

rotating the space so that

. The right-hand-rule parity can be checked by

rotating the space so that

![]() and

and

![]() in

which case

in

which case

![]() . Thus, the cross

product points ``up'' relative to the

. Thus, the cross

product points ``up'' relative to the

![]() plane for

plane for

![]() and ``down'' for

and ``down'' for

![]() .

.

Mass Moment of Inertia as a Cross Product

In Eq.![]() (B.14) above, the mass moment of inertia was expressed

in terms of orthogonal projection as

(B.14) above, the mass moment of inertia was expressed

in terms of orthogonal projection as

![]() , where

, where

![]() . In terms of the vector cross

product, we can now express it as

. In terms of the vector cross

product, we can now express it as

Tangential Velocity as a Cross Product

Referring again to Fig.B.4, we can write the

tangential velocity vector

![]() as a vector cross product of

the angular-velocity vector

as a vector cross product of

the angular-velocity vector

![]() (§B.4.11) and the position

vector

(§B.4.11) and the position

vector

![]() :

:

To see this, let's first check its direction and then its magnitude. By the right-hand rule,

Angular Momentum

The angular momentum of a mass ![]() rotating in a circle of

radius

rotating in a circle of

radius ![]() with angular velocity

with angular velocity ![]() (rad/s), is defined by

(rad/s), is defined by

Relation of Angular to Linear Momentum

Recall (§B.3) that the momentum of a mass ![]() traveling

with velocity

traveling

with velocity ![]() in a straight line is given by

in a straight line is given by

Thus, the angular momentum

Linear momentum can be viewed as a renormalized special case of angular momentum in which the radius of rotation goes to infinity.

Angular Momentum Vector

Like linear momentum, angular momentum is fundamentally a vector in

![]() . The definition of the previous section suffices when the

direction does not change, in which case we can focus only on its

magnitude

. The definition of the previous section suffices when the

direction does not change, in which case we can focus only on its

magnitude ![]() .

.

More generally, let

![]() denote the 3-space coordinates

of a point-mass

denote the 3-space coordinates

of a point-mass ![]() , and let

, and let

![]() denote its velocity

in

denote its velocity

in ![]() . Then the instantaneous angular momentum vector

of the mass relative to the origin (not necessarily rotating about a

fixed axis) is given by

. Then the instantaneous angular momentum vector

of the mass relative to the origin (not necessarily rotating about a

fixed axis) is given by

where

For the special case in which

![]() is orthogonal to

is orthogonal to

![]() , as in Fig.B.4, we have that

, as in Fig.B.4, we have that

![]() points, by the right-hand rule, in the direction of the angular

velocity vector

points, by the right-hand rule, in the direction of the angular

velocity vector

![]() (up out of the page), which is

satisfying. Furthermore, its magnitude is given by

(up out of the page), which is

satisfying. Furthermore, its magnitude is given by

In the more general case of an arbitrary mass velocity vector

![]() , we know from §B.4.12 that the magnitude of

, we know from §B.4.12 that the magnitude of

![]() equals the product of the distance from the axis

of rotation to the mass, i.e.,

equals the product of the distance from the axis

of rotation to the mass, i.e.,

![]() , times the length of

the component of

, times the length of

the component of

![]() that is orthogonal to

that is orthogonal to

![]() , i.e.,

, i.e.,

![]() , as needed.

, as needed.

It can be shown that vector angular momentum, as defined, is conserved.B.22 For example, in an orbit, such as that of the moon around the earth, or that of Halley's comet around the sun, the orbiting object speeds up as it comes closer to the object it is orbiting. (See Kepler's laws of planetary motion.) Similarly, a spinning ice-skater spins faster when pulling in arms to reduce the moment of inertia about the spin axis. The conservation of angular momentum can be shown to result from the principle of least action and the isotrophy of space [270, p. 18].

Angular Momentum Vector in Matrix Form

The two cross-products in Eq.![]() (B.19) can be written out with the help

of the vector analysis identityB.23

(B.19) can be written out with the help

of the vector analysis identityB.23

where

![$\displaystyle \mathbf{I}\underline{\omega}\eqsp

\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

I_{1...

...begin{array}{c} \omega_1 \\ [2pt] \omega_2 \\ [2pt] \omega_3\end{array}\right]

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2872.png)

The matrix

The vector angular momentum of a rigid body is obtained by summing the angular momentum of its constituent mass particles. Thus,

In summary, the angular momentum vector

![]() is given by the mass

moment of inertia tensor

is given by the mass

moment of inertia tensor

![]() times the angular-velocity vector

times the angular-velocity vector

![]() representing the axis of rotation.

representing the axis of rotation.

Note that the angular momentum vector

![]() does not in general

point in the same direction as the angular-velocity vector

does not in general

point in the same direction as the angular-velocity vector

![]() . We

saw above that it does in the special case of a point mass traveling

orthogonal to its position vector. In general,

. We

saw above that it does in the special case of a point mass traveling

orthogonal to its position vector. In general,

![]() and

and

![]() point

in the same direction whenever

point

in the same direction whenever

![]() is an eigenvector of

is an eigenvector of

![]() , as will be discussed further below (§B.4.16). In this

case, the rigid body is said to be dynamically balanced.B.24

, as will be discussed further below (§B.4.16). In this

case, the rigid body is said to be dynamically balanced.B.24

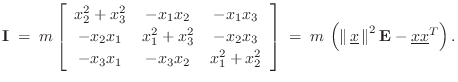

Mass Moment of Inertia Tensor

As derived in the previous section, the moment of inertia

tensor, in 3D Cartesian coordinates, is a three-by-three matrix

![]() that can be multiplied by any angular-velocity vector to

produce the corresponding angular momentum vector for either a point

mass or a rigid mass distribution. Note that the origin of the

angular-velocity vector

that can be multiplied by any angular-velocity vector to

produce the corresponding angular momentum vector for either a point

mass or a rigid mass distribution. Note that the origin of the

angular-velocity vector

![]() is always fixed at

is always fixed at

![]() in the space

(typically located at the center of mass). Therefore, the moment of

inertia tensor

in the space

(typically located at the center of mass). Therefore, the moment of

inertia tensor

![]() is defined relative to that origin.

is defined relative to that origin.

The moment of inertia tensor can similarly be used to compute the

mass moment of inertia for any normalized angular velocity

vector

![]() as

as

Since rotational energy is defined as

We can show Eq.

where again

![]() denotes the three-by-three identity matrix, and

denotes the three-by-three identity matrix, and

which agrees with Eq.

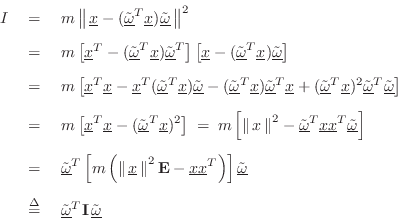

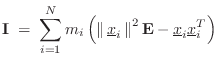

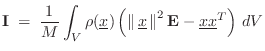

For a collection of ![]() masses

masses ![]() located at

located at

![]() , we

simply sum over their masses to add up the moments of inertia:

, we

simply sum over their masses to add up the moments of inertia:

Simple Example

Consider a mass ![]() at

at

![]() . Then the mass moment of inertia

tensor is

. Then the mass moment of inertia

tensor is

![$\displaystyle \mathbf{I}\eqsp m \left(\left\Vert\,\underline{x}\,\right\Vert^2\...

...ay}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0\\ [2pt]

0 & 1 & 0\\ [2pt]

0 & 0 & 1

\end{array}\right].

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2891.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

I \eqsp \underline{\tilde{\omega}}^T\mathbf{I}\,\underline{\...

...{array}{c} 1 \\ [2pt] 0 \\ [2pt] 0\end{array}\right]m \eqsp 0.

\end{displaymath}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2893.png)

![$\displaystyle I \eqsp \underline{\tilde{\omega}}^T\mathbf{I}\,\underline{\tilde...

...]

\left[\begin{array}{c} 0 \\ [2pt] 1 \\ [2pt] 0\end{array}\right] \eqsp m x^2

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2895.png)

Example with Coupled Rotations

Now let the mass ![]() be located at

be located at

![]() so that

so that

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\mathbf{I}&=& m \left(\left\Vert\,\underline{x}\,\right\Vert^2...

... & 0\\ [2pt]

-1 & 1 & 0\\ [2pt]

0 & 0 & 2

\end{array}\right].

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2897.png)

We expect

![]() to yield zero for the moment of inertia, and

sure enough

to yield zero for the moment of inertia, and

sure enough

![]() . Similarly, the vector angular

momentum is zero, since

. Similarly, the vector angular

momentum is zero, since

![]() .

.

For

![]() , the result is

, the result is

![\begin{displaymath}

\mathbf{I}\eqsp

\begin{array}{r}\left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 ...

...egin{array}{c} 1 \\ [2pt] 0 \\ [2pt] 0\end{array}\right]m = m,

\end{displaymath}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2902.png)

Off-Diagonal Terms in Moment of Inertia Tensor

This all makes sense, but what about those ![]() off-diagonal terms in

off-diagonal terms in

![]() ? Consider the vector angular momentum (§B.4.14):

? Consider the vector angular momentum (§B.4.14):

![$\displaystyle \underline{L}\eqsp \mathbf{I}\,\underline{\omega}\eqsp

m\left[\b...

...begin{array}{c} \omega_1 \\ [2pt] \omega_2 \\ [2pt] \omega_3\end{array}\right]

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2907.png)

Principal Axes of Rotation

A principal axis of rotation (or principal direction) is

an eigenvector of the mass moment of inertia tensor (introduced

in the previous section) defined relative to some point (typically the

center of mass). The corresponding eigenvalues are called the

principal moments of inertia.

Because the moment of inertia tensor is defined relative to the point

![]() in the space, the principal axes all pass through that point

(usually the center of mass).

in the space, the principal axes all pass through that point

(usually the center of mass).

As derived above (§B.4.14), the angular momentum vector is given by the moment of inertia tensor times the angular-velocity vector:

Positive Definiteness of the Moment of Inertia Tensor

From the form of the moment of inertia tensor introduced in Eq.![]() (B.24)

(B.24)

![\begin{eqnarray*}

I &=& \underline{\tilde{\omega}}^T\mathbf{I}\,\underline{\tild...

...\cal P}_{\underline{x}}(\underline{\tilde{\omega}})\right] \ge 0

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2916.png)

since

![]() is unit length, and projecting it onto any other vector

can only shorten it or leave it unchanged. That is,

is unit length, and projecting it onto any other vector

can only shorten it or leave it unchanged. That is,

![]() , with equality occurring for

, with equality occurring for

![]() for any nonzero

for any nonzero

![]() . Zooming out,

of course we expect any moment of inertia

. Zooming out,

of course we expect any moment of inertia ![]() for a positive

mass

for a positive

mass ![]() to be nonnegative. Thus,

to be nonnegative. Thus,

![]() is symmetric

nonnegative definite. If furthermore

is symmetric

nonnegative definite. If furthermore

![]() and

and

![]() are not

collinear, i.e., if there is any nonzero angle between them, then

are not

collinear, i.e., if there is any nonzero angle between them, then

![]() is positive definite (and

is positive definite (and ![]() ). As is well known in

linear algebra [329], real, symmetric, positive-definite

matrices have orthogonal eigenvectors and real, positive

eigenvalues. In this context, the orthogonal eigenvectors are

called the principal axes of rotation. Each corresponding

eigenvalue is the moment of inertia about that principal axis--the

corresponding principal moment of inertia. When angular velocity

vectors

). As is well known in

linear algebra [329], real, symmetric, positive-definite

matrices have orthogonal eigenvectors and real, positive

eigenvalues. In this context, the orthogonal eigenvectors are

called the principal axes of rotation. Each corresponding

eigenvalue is the moment of inertia about that principal axis--the

corresponding principal moment of inertia. When angular velocity

vectors

![]() are expressed as a linear combination of the principal

axes, there are no cross-terms in the moment of inertia tensor--no

so-called products of inertia.

are expressed as a linear combination of the principal

axes, there are no cross-terms in the moment of inertia tensor--no

so-called products of inertia.

The three principal axes are unique when the eigenvalues of

![]() (principal moments of inertia) are distinct. They are

not unique when there are repeated eigenvalues, as in the example

above of a disk rotating about any of its diameters

(§B.4.4). In that example, one principal

axis, the one corresponding to eigenvalue

(principal moments of inertia) are distinct. They are

not unique when there are repeated eigenvalues, as in the example

above of a disk rotating about any of its diameters

(§B.4.4). In that example, one principal

axis, the one corresponding to eigenvalue ![]() , was

, was

![]() (i.e.,

orthogonal to the disk and passing through its center), while any two

orthogonal diameters in the plane of the disk may be chosen as the

other two principal axes (corresponding to the repeated eigenvalue

(i.e.,

orthogonal to the disk and passing through its center), while any two

orthogonal diameters in the plane of the disk may be chosen as the

other two principal axes (corresponding to the repeated eigenvalue

![]() ).

).

Symmetry of the rigid body about any axis

![]() (passing through the

origin) means that

(passing through the

origin) means that

![]() is a principal direction. Such a symmetric

body may be constructed, for example, as a solid of

revolution.B.26In rotational dynamics, this case is known as the symmetric top

[270]. Note that the center of mass will lie

somewhere along an axis of symmetry. The other two principal axes can

be arbitrarily chosen as a mutually orthogonal pair in the (circular)

plane orthogonal to the

is a principal direction. Such a symmetric

body may be constructed, for example, as a solid of

revolution.B.26In rotational dynamics, this case is known as the symmetric top

[270]. Note that the center of mass will lie

somewhere along an axis of symmetry. The other two principal axes can

be arbitrarily chosen as a mutually orthogonal pair in the (circular)

plane orthogonal to the

![]() axis, intersecting at the

axis, intersecting at the

![]() axis. Because of the circular symmetry about

axis. Because of the circular symmetry about

![]() , the two

principal moments of inertia in that plane are equal. Thus the moment

of inertia tensor can be diagonalized to look like

, the two

principal moments of inertia in that plane are equal. Thus the moment

of inertia tensor can be diagonalized to look like

![$\displaystyle \mathbf{I}= \left[\begin{array}{ccc}

I_1 & 0 & 0\\ [2pt]

0 & I_2 & 0\\ [2pt]

0 & 0 & I_2

\end{array}\right],

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2925.png)

Rotational Kinetic Energy Revisited

If a point-mass is located at

![]() and is rotating about an

axis-of-rotation

and is rotating about an

axis-of-rotation

![]() with angular velocity

with angular velocity ![]() , then the

distance from the rotation axis to the mass is

, then the

distance from the rotation axis to the mass is

![]() ,

or, in terms of the vector cross product,

,

or, in terms of the vector cross product,

![]() . The tangential velocity of the mass is

then

. The tangential velocity of the mass is

then ![]() , so that the kinetic energy can be expressed as

(cf. Eq.

, so that the kinetic energy can be expressed as

(cf. Eq.![]() (B.23))

(B.23))

where

In a collection of ![]() masses

masses ![]() having velocities

having velocities

![]() , we of

course sum the individual kinetic energies to get the total kinetic

energy.

, we of

course sum the individual kinetic energies to get the total kinetic

energy.

Finally, we may also write the rotational kinetic energy as half the inner product of the angular-velocity vector and the angular-momentum vector:B.27

Torque

![\includegraphics[width=1.1in]{eps/torque}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2937.png) |

When twisting things, the rotational force we apply about the center

is called a torque (or moment, or moment of

force). Informally, we think of the torque as the tangential

applied force ![]() times the moment arm (length of the

lever arm)

times the moment arm (length of the

lever arm) ![]()

as depicted in Fig.B.7. The moment arm is the distance from the applied force to the point being twisted. For example, in the case of a wrench turning a bolt,

For more general applied forces

![]() , we may compute the

tangential component

, we may compute the

tangential component

![]() by projecting

by projecting

![]() onto the

tangent direction. More precisely, the torque

onto the

tangent direction. More precisely, the torque ![]() about the

origin

about the

origin

![]() applied at a point

applied at a point

![]() may be defined by

may be defined by

where

Note that the torque vector

![]() is orthogonal to both the lever

arm and the tangential-force direction. It thus points in the

direction of the angular velocity vector (along the axis of rotation).

is orthogonal to both the lever

arm and the tangential-force direction. It thus points in the

direction of the angular velocity vector (along the axis of rotation).

The torque magnitude is

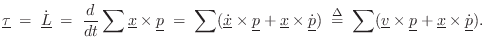

Newton's Second Law for Rotations

The rotational version of Newton's law ![]() is

is

where

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\tau &=& \dot{L} \,\eqss \, I\dot{\omega}\,\isdefss \, I\alpha\\ [5pt]

f &=& \dot{p} \,\eqss \, m\dot{v}\,\isdefss \, ma

\end{eqnarray*}](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2949.png)

To show that Eq.![]() (B.28) results from Newton's second law

(B.28) results from Newton's second law ![]() ,

consider again a mass

,

consider again a mass ![]() rotating at a distance

rotating at a distance ![]() from an axis

of rotation, as in §B.4.3 above, and

let

from an axis

of rotation, as in §B.4.3 above, and

let ![]() denote a tangential force on the mass, and

denote a tangential force on the mass, and ![]() the corresponding tangential acceleration. Then we have, by Newton's

second law,

the corresponding tangential acceleration. Then we have, by Newton's

second law,

In summary, force equals the time-derivative of linear momentum, and torque equals the time-derivative of angular momentum. By Newton's laws, the time-derivative of linear momentum is mass times acceleration, and the time-derivative of angular momentum is the mass moment of inertia times angular acceleration:

Equations of Motion for Rigid Bodies

We are now ready to write down the general equations of motion for

rigid bodies in terms of ![]() for the center of mass and

for the center of mass and

![]() for the rotation of the body about its center of mass.

for the rotation of the body about its center of mass.

As discussed above, it is useful to decompose the motion of a rigid body into

- (1)

- the linear velocity

of its center of mass, and

of its center of mass, and

- (2)

- its angular velocity

about its center of mass.

about its center of mass.

The linear motion is governed by Newton's second law

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the total mass,

is the total mass,

![]() is the

velocity of the center-of-mass, and

is the

velocity of the center-of-mass, and

![]() is the sum of all external

forces on the rigid body. (Equivalently,

is the sum of all external

forces on the rigid body. (Equivalently,

![]() is the sum of the

radial force components pointing toward or away from the center of

mass.) Since this is so straightforward, essentially no harder than

dealing with a point mass, we will not consider it further.

is the sum of the

radial force components pointing toward or away from the center of

mass.) Since this is so straightforward, essentially no harder than

dealing with a point mass, we will not consider it further.

The angular motion is governed the rotational version of Newton's second law introduced in §B.4.19:

where

The driving torque

![]() is given by the resultant moment of

the external forces, using Eq.

is given by the resultant moment of

the external forces, using Eq.![]() (B.27) for each external force to

obtain its contribution to the total moment. In other words, the

external moments (tangential forces times moment arms) sum up for the

net torque just like the radial force components summed to produce the

net driving force on the center of mass.

(B.27) for each external force to

obtain its contribution to the total moment. In other words, the

external moments (tangential forces times moment arms) sum up for the

net torque just like the radial force components summed to produce the

net driving force on the center of mass.

Body-Fixed and Space-Fixed Frames of Reference

Rotation is always about some (instantaneous) axis of rotation that is

free to change over time. It is convenient to express rotations in a

coordinate system having its origin (

![]() ) located at the

center-of-mass of the rigid body (§B.4.1), and its coordinate axes

aligned along the principal directions for the body (§B.4.16).

This body-fixed frame then moves within a stationary

space-fixed frame (or ``star frame'').

) located at the

center-of-mass of the rigid body (§B.4.1), and its coordinate axes

aligned along the principal directions for the body (§B.4.16).

This body-fixed frame then moves within a stationary

space-fixed frame (or ``star frame'').

In Eq.![]() (B.29) above, we wrote down Newton's second law for angular

motion in the body-fixed frame, i.e., the coordinate system

having its origin at the center of mass. Furthermore, it is simplest

(

(B.29) above, we wrote down Newton's second law for angular

motion in the body-fixed frame, i.e., the coordinate system

having its origin at the center of mass. Furthermore, it is simplest

(

![]() is diagonal) when its axes lie along principal directions

(§B.4.16).

is diagonal) when its axes lie along principal directions

(§B.4.16).

As an example of a local body-fixed coordinate system, consider a spinning top. In the body-fixed frame, the ``vertical'' axis coincides with the top's axis of rotation (spin). As the top loses rotational kinetic energy due to friction, the top's rotation-axis precesses around a circle, as observed in the space-fixed frame. The other two body-fixed axes can be chosen as any two mutually orthogonal axes intersecting each other (and the spin axis) at the center of mass, and lying in the plane orthogonal to the spin axis. The space-fixed frame is of course that of the outside observer's inertial frameB.28in which the top is spinning.

Angular Motion in the Space-Fixed Frame

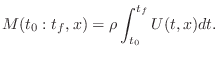

Let's now consider angular motion in the presence of linear motion of the center of mass. In general, we have [270]

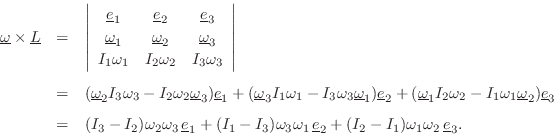

Euler's Equations for Rotations in the Body-Fixed Frame

Suppose now that the body-fixed frame is rotating in the space-fixed

frame with angular velocity

![]() . Then the total torque on the rigid

body becomes [270]

. Then the total torque on the rigid

body becomes [270]

Similarly, the total external forces on the center of mass become

![$\displaystyle \underline{L}\eqsp \left[\begin{array}{c} I_1\omega_1 \\ [2pt] I_2\omega_2 \\ [2pt] I_3\omega_3\end{array}\right]

$](http://www.dsprelated.com/josimages_new/pasp/img2969.png)

Substituting this result into Eq.![]() (B.30), we obtain the following

equations of angular motion for an object rotating in the body-fixed

frame defined by its three principal axes of rotation:

(B.30), we obtain the following

equations of angular motion for an object rotating in the body-fixed

frame defined by its three principal axes of rotation:

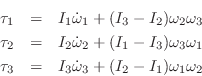

These are call Euler's

equations:B.29Since these equations are in the body-fixed frame, ![]() is the mass

moment of inertia about principal axis

is the mass

moment of inertia about principal axis ![]() , and

, and ![]() is the

angular velocity about principal axis

is the

angular velocity about principal axis ![]() .

.

Examples

For a uniform sphere, the cross-terms disappear and the moments of

inertia are all the same, leaving

![]() , for

, for ![]() .

Since any three orthogonal vectors can serve as eigenvectors of the

moment of inertia tensor, we have that, for a uniform sphere, any

three orthogonal axes can be chosen as principal axes.

.

Since any three orthogonal vectors can serve as eigenvectors of the

moment of inertia tensor, we have that, for a uniform sphere, any

three orthogonal axes can be chosen as principal axes.

For a cylinder that is not spinning about its axis, we similarly

obtain two uncoupled equations

![]() , for

, for ![]() , given

, given

![]() (no spin). Note, however, that if we replace the

circular cross-section of the cylinder by an ellipse, then

(no spin). Note, however, that if we replace the

circular cross-section of the cylinder by an ellipse, then

![]() and there is a coupling term that drives

and there is a coupling term that drives

![]() (unless

(unless ![]() happens to cancel it).

happens to cancel it).

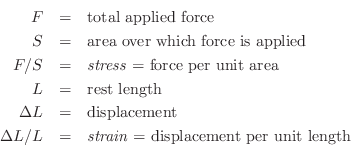

Properties of Elastic Solids

Young's Modulus

Young's modulus can be thought of as the spring constant

for solids. Consider an ideal rod (or bar) of length ![]() and

cross-sectional area

and

cross-sectional area ![]() . Suppose we apply a force

. Suppose we apply a force ![]() to the face of

area

to the face of

area ![]() , causing a displacement

, causing a displacement ![]() along the axis of the rod.

Then Young's modulus

along the axis of the rod.

Then Young's modulus ![]() is given by

is given by

For wood, Young's modulus ![]() is on the order of

is on the order of ![]() N/m

N/m![]() .

For aluminum, it is around

.

For aluminum, it is around ![]() (a bit higher than glass which is near

(a bit higher than glass which is near

![]() ), and structural steel has

), and structural steel has

![]() [180].

[180].

Young's Modulus as a Spring Constant

Recall (§B.1.3) that Hooke's Law defines a spring

constant ![]() as the applied force

as the applied force ![]() divided by the spring

displacement

divided by the spring

displacement ![]() , or

, or ![]() . An elastic solid can be viewed as a

bundle of ideal springs. Consider, for example, an ideal

bar (a rectangular solid in which one dimension, usually its

longest, is designated its length

. An elastic solid can be viewed as a

bundle of ideal springs. Consider, for example, an ideal

bar (a rectangular solid in which one dimension, usually its

longest, is designated its length ![]() ), and consider compression by

), and consider compression by

![]() along the length dimension. The length of each spring in

the bundle is the length of the bar, so that each spring constant

along the length dimension. The length of each spring in

the bundle is the length of the bar, so that each spring constant ![]() must be inversely proportional to

must be inversely proportional to ![]() ; in particular, each doubling of

length

; in particular, each doubling of

length ![]() doubles the length of each ``spring'' in the bundle, and

therefore halves its stiffness. As a result, it is useful to

normalize displacement

doubles the length of each ``spring'' in the bundle, and

therefore halves its stiffness. As a result, it is useful to

normalize displacement ![]() by length

by length ![]() and use relative

displacement

and use relative

displacement

![]() . We need displacement per unit length

because we have a constant spring compliance per unit length.

. We need displacement per unit length

because we have a constant spring compliance per unit length.

The number of springs in parallel is proportional to the

cross-sectional area ![]() of the bar. Therefore, the force applied to

each spring is proportional to the total applied force

of the bar. Therefore, the force applied to